by Brooks Riley

by Brooks Riley

by Thomas O’Dwyer

“There is no question I love her deeply … I keep remembering her body, her nakedness, the day with her, our bottle of champagne … She says she thinks of me all the time (as I do of her) and her only fear is that being apart, we may gradually cease to believe that we are loved, that the other’s love for us goes on and is real. As I kissed her she kept saying, ‘I am happy, I am at peace now.’ And so was I.”

These romantic diary entries of a middle-aged man smitten with a new love would seem unremarkable, commonplace, but for one thing. The author was a Trappist monk, a priest in one of the most strict Catholic monastic orders, bound by vows of poverty, chastity, obedience and silence. Moreover, he was world famous in his monkishness as the author of best-selling books on spirituality, monastic vocation and contemplation. He was credited with drawing vast numbers of young men into seminaries around the world during the last modern upsurge of religious fervour after World War II. Two years after this tryst, the world’s most famous monk was found dead in a room near a conference centre in Bangkok, Thailand. He was on his back, wearing only shorts, electrocuted by a Hitachi floor-fan lying on his chest. In the tabloids there were dark mutterings of divine retribution, suicide, even a CIA murder conspiracy.

So passed Thomas Merton, who shot to fame in 1948 when he published his memoir The Seven Storey Mountain. It was the tale of a journey from a life of “beer, bewilderment, and sorrow” to a seminary in the Order of Cistercians of Strict Observance, commonly known as Trappists. A steady output of books, essays and poems made him one of the best known and loved spiritual writers of his day. It also made millions of dollars for his Trappist monastery, the Abbey of Gethsemani in Nelson county, Kentucky. Because of him, droves of demobbed soldiers and marines clamoured to become monks. Read more »

by Joshua Wilbur

tl; dr:

Skim-reading is a bad habit, all things considered.

It’s detrimental to our sense of time and place. Screen technologies are fundamentally changing not only how we read but also how we think and what we remember.

But readers shouldn’t take all the blame. Writers, editors, and creatives of all stripes must adapt in order to counteract our tendency to skim-read everything in sight.

For the uninitiated, “tl; dr” stands for “too long, didn’t read.” It’s a handy piece of internet slang, used on discussion forums to briefly summarize a dense “wall of text.” A good tl;dr distills the key points of a lengthy post, saving the hurried reader minutes of time.

It’s not unlike the BLUF (bottom line up front) technique commonly used in business and military writing, in which “conclusions and recommendations are placed at the beginning of the text, rather than the end, in order to facilitate rapid decision making.”

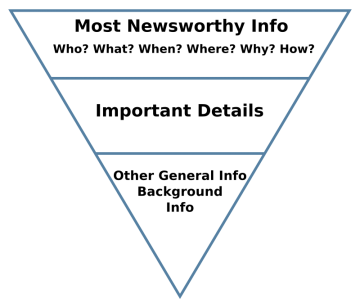

You could also imagine tl;dr as the internet’s snarkier version of the Inverted Pyramid method used by journalists. The method dictates that the most significant information should appear at the top of any news article —front and center— with supporting details falling below. To “bury the lead” is to fumble the pyramid’s orientation and waste the reader’s time as a result.

Arguably, tl; dr is only the latest expression of an old petition from readers: get to the point; give me the gist; just the facts, ma’am. We’ve always been pressed for time and concerned with the most salient points, especially when it comes to the news. For many of us, “reading the newspaper” has long amounted to skimming the headlines.

So what’s the big deal? Read more »

by Mary Hrovat

The spring ephemeral wildflowers of the Midwest are generally not large or showy. In a relatively short time during one of the less promising parts of the year, these perennial plants must put out leaves and flowers and reproduce, all before disappearing until the next spring. Still, they light up the woods for me every year despite their relatively modest circumstances.

The spring ephemeral wildflowers of the Midwest are generally not large or showy. In a relatively short time during one of the less promising parts of the year, these perennial plants must put out leaves and flowers and reproduce, all before disappearing until the next spring. Still, they light up the woods for me every year despite their relatively modest circumstances.

One of the earliest spring ephemerals, harbinger of spring, may be the most inconspicuous. The plant is usually no more than a few inches tall when it blooms, and if you don’t keep an eye out for it, you could walk right by and not know it’s there. Unless you kneel down and look closely, the leaves are little more than a small green patch dotted by tiny white flowers. Closer inspection reveals that the flowers have five white petals and deep red anthers, which darken with time and give the flowers a charming salt-and-pepper look. Harbinger of spring can appear as early as February, when the weather has been cold for months and the trees are bare. It’s a minute but electrifying herald of warmer and greener days to come. Read more »

by Gabrielle C. Durham

![]()

Have you ever been asked to donate to the worthy cause of sending the Lady Loins to the state semi-finals? I have, and I think I gave a couple bucks because of the doubtlessly unintentional prurience of the street fund-raising efforts of these aspiring young athletes and their lacking sign-makers.

As an editor, I think everyone needs an editor’s eye to pass over any written material, including my own. When we review our own writing, our brain fills in any lacunae in logic or syntax. This does not happen when we read other authors’ output, at least not as often. If you want to point the finger at why this occurs no matter how conscientious we are, go ahead and blame science.

You have likely seen the memes that dot social media about being able to read garbled words and sentences such as:

Tehse wrods may look lkie nosnesne, but yuo can raed tehm, cna’t yuo? [from mnn.com]

When relatively simple (one- to two-syllable words) words have their first and last letters in the correct place, our brains decipher them fairly quickly. Why does this happen? Because we rely on context to determine meaning. Whether we are counting the number of letters when we play Hangman, watching a show like “Wheel of Fortune,” or working on a crossword puzzle, our brains are analyzing the context to create solutions.

Your brain wants to fill in a pattern so that the jumble make sense. Measuring pattern recognition is one of the ways to test IQ, intelligence, and job fit (how you think being perhaps more important than what you think). According to this article from Frontiers of Neuroscience, “A major purpose of the present article is to forward the proposal that not only is pattern processing necessary for higher brain functions of humans, but [superior pattern processing] is sufficient to explain many such higher brain functions including creativity, imagination, language, and magical thinking.” Patterns and context matter tremendously.

So, what does this have to do with needing an editor forthwith? It comes down to this: You can’t be trusted. Read more »

Eiffel Tower, Paris, March of 2014.

by Jeroen Bouterse

When Socrates’ students enter his cell, in subdued spirits, their mentor has just been released from his shackles. After having his wife and baby sent away, Socrates spends some time sitting up on the bed, rubbing his leg, cheerfully remarking on how it feels much better now, after the pain.

When Socrates’ students enter his cell, in subdued spirits, their mentor has just been released from his shackles. After having his wife and baby sent away, Socrates spends some time sitting up on the bed, rubbing his leg, cheerfully remarking on how it feels much better now, after the pain.

The Phaedo, Plato’s vision of Socrates’ final conversation with his students before drinking the hemlock, is a literary piece overflowing with meaning and metaphor. Its main topic is the immortality of the soul. Socrates’ predicament provides not just the occasion but also a handy analogy: Socrates sees his death as the release of the soul from the bonds of the body (67d). His students are not so sure.

With Plato, every moral, existential and philosophical question is in the end related to a problem of knowledge. So when, in the last hours of his earthly life, halfway through Plato’s dialogue, Socrates suddenly starts off on a lecture about the epistemological paradoxes of the natural sciences, no-one is too surprised. After all, the question whether death is bad for you naturally flows into the question whether the soul can actually die, and therefore into the question what kind of thing the soul actually is, and what we can say about it and how. It is Socrates’ excursion into science that I want to zoom in on here. Read more »

by Daniel Ranard

You must have seen the iconic image of the blue-white earth, perfectly round against the black of space. How did NASA produce the famous “Blue Marble” image? Actually, Harrison Schmitt just snapped a photo on his 70mm Hasselblad. Or maybe it was his buddy Eugene Cernan, or Ron Evans – their accounts differ – but the magic behind the shot was only location, location, location: they were aboard the Apollo 17 in 1972.

Since then, NASA has produced images increasingly strange and absorbing. Take a look at the “Pillars of Creation” if you never have. Click it, the inline image won’t do. That’s from the Hubble telescope, not a Hasselblad handheld.

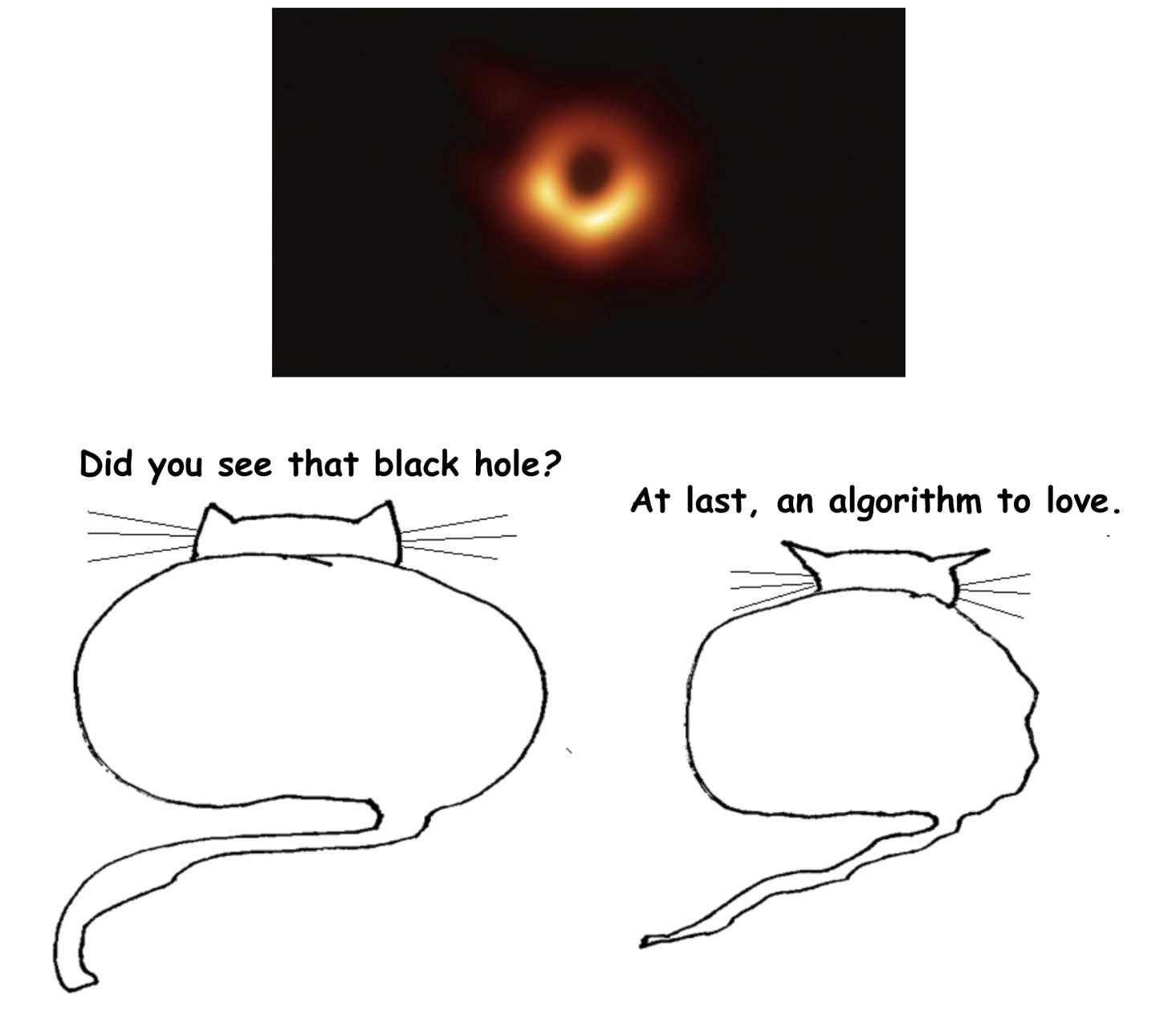

Meanwhile, this week an international collaboration gave us the world’s first photograph of a black hole. The image appears diminutive, nearly abstract. It’s no blue marble; it offers no sense of scale. Though we may obtain better images soon, the first image has its own allure. The photograph is appropriately intangible, desiring of context, not quite structureless.

Maybe “photograph” is a stretch. For one, the choice of orange is purely aesthetic. The actual light captured on earth was at radio wavelengths (radio waves are a type of light), much longer than the eye can see. The orange-yellow variations depicted in the image do not correspond to color at all: scientists simply colored the brighter emissions yellow, the dimmer ones orange. Besides, even if we could see light at radio wavelengths, no one person could see the black hole as pictured. Multiple telescopes collected the light thousands of kilometers apart, and sophisticated algorithms reconstructed the final image by interpolating between sparse data points.

Should we marvel at this image as a photograph? Or is it a more abstract visualization of scientific data? First let’s ask what it means to see a thing, at least usually. Read more »

by John Allen Paulos

I’ve always liked stories that depended on mistaken identity, a very old theme in general. Having a degree in mathematical logic, I was also drawn to the subject on a more theoretical level, on which lies Gettier’s Paradox.

I’ve always liked stories that depended on mistaken identity, a very old theme in general. Having a degree in mathematical logic, I was also drawn to the subject on a more theoretical level, on which lies Gettier’s Paradox.

Since Plato and the ancient Greeks, knowledge has been taken by many philosophers of science to be justified true belief. A subject S is said to know a proposition P if P is true, S believes that P is true, and S is justified in believing that P is true. The philosopher Edmund L. Gettier showed in 1963 that these three ancient conditions are not sufficient to ensure knowledge of P. His counterexamples to a straightforward understanding of knowledge are paradoxical and seem particularly prevalent in politics. For me, this is part of their appeal since politics and mathematical logic occupy such different realms of cognitive space.

To provide a topical one consider the 2016 election. Trump and Clinton in October before the 2016 election were certainly evaluating their chances to win the election. Trump had strong evidence for the following compound proposition:

Proposition (1): Clinton is the person who will be elected, and there was a little clock that might help her out mounted in her lectern during the final debate. Trump’s evidence for (1) might be that the polls were showing Clinton was going to win the election and President Obama and the Democratic establishment were strongly supporting her. He also noticed the clock as he hovered around Clinton’s lectern during the debate.

If (1) is true, it implies

Proposition (2): the person who will get elected had a lectern with a little clock mounted in it. Trump saw that (1) implied (2) and thus accepted (2) on the basis of (1), for which he had strong evidence. Clearly Trump was justified in believing that (2) was true.

So far, so good. But unknown to Trump at that time, was that he, not Clinton, would be elected. Read more »

by Abigail Akavia

Israel’s minister of justice stars in an ad for the perfume Fascism—if you follow Israeli politics even superficially, you probably have heard about this election campaign video for the New Right party, which sparked controversy in Israeli as well as international media. If you’ve actually watched it, you may have realized it is (or purports to be) ironic, though you would need the subtitled version to make the irony clear. To a non-Hebrew speaker watching the non-subtitled version, Ayelet Shaked seems to seductively model the perfume Fascism. Shot in black-and-white, she has the affectations of a sultry film star, complete with hair flip, donning of blazer (at least, thankfully, she is not filmed taking the blazer off), and caressing of a stair railing. A sexy female voice-over croons Shaked’s proposed measures for the restraining of judicial powers, a “judicial revolution” which has been her main goal as justice minister, and which she hopes to further in the next administration, to be assembled following the upcoming elections for parliament tomorrow (April 9th). Shaked has been vocal and active against what right-wingers have long considered the ultra-liberal tendencies of Israel’s Supreme Court—namely, its concern for the liberties and human rights of Palestinians.

For example, the ministry under her lead has transferred the jurisdiction of the occupied territories from the Supreme Court to the Jerusalem court of administrative affairs, especially in matters pertaining to building and construction, and entry and exit. She has also pushed for a law that would allow the parliament to override the Supreme Court’s authority to disqualify any law contradicting The Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty, which enjoys super-legal status (Israel does not have a constitution, but a set of Basic or Constitutional Laws that can only be changed by a supermajority in parliament). That the Supreme Court should uphold the Human Dignity and Liberty of individuals and groups that are not part of the hegemonic majority (i.e. non-Jewish) is anathema to Shaked and her far-right party members. In an Israel which is clearly more right-leaning than ever, the sentiment that Palestinians in the occupied territories (in itself a term that is falling out of the norm and into the purview of the “delusional left”) are undeserving of basic human rights or simple human dignity, is becoming alarmingly common.

But back to the perfume ad: is Shaked simply saying, “I am a proud fascist”? The controversy, no doubt deliberate, revolved partly around this issue: that the subtle irony of the video, not to mention its actual punch-line, might be lost on anyone who mistakenly takes the ad at face value. I’ll suggest below how we might unpack this irony, both in its local context and by comparing it to Melania Trump’s infamous “I really don’t care” jacket, another instance of a plausible fascist performance with multi-layered significance. Read more »

by Thomas R. Wells

Why do you love me? Tell me the reasons.

I love you because you are you. If I loved you for reasons then I wouldn’t love you, but the reasons. I would have to leave you if someone better came along.

Movies, music and novels portray a particular ideal of romantic love almost relentlessly. Love is something that happens to you, something you fall into even against your will or better judgement. It is something to be experienced as good in itself and joyfully submitted to, not something that should be questioned.

Movies, music and novels portray a particular ideal of romantic love almost relentlessly. Love is something that happens to you, something you fall into even against your will or better judgement. It is something to be experienced as good in itself and joyfully submitted to, not something that should be questioned.

Is this person good for me? Would I be good for them? To ask such questions would betray a spirit of rational calculation that has no place in matters of the heart. The only question you should be asking is whether it is the real thing, which can be assessed by the strength of your feelings for the other. For authentic love, no price is too great.

It should be pretty clear that this is a pathological idea of love that — thanks to its immense popularity — has trained generations of people into attitudes and expectations that cause them and others great unhappiness. How many stalkers are simply following what the movies have taught them and risking all for love? How many people find that love has attached them to a person who isn’t worthy of their commitment, or who even exploits it and causes them harm? Love as authenticity may be a delicious fantasy, but it is a terrible way to try to live. Read more »

by Joseph Shieber

If you’re like me, when you read something on 3QD you often have a cup of coffee ready to hand. Perhaps you’re at your desk at work on your computer, with a mug near your mousepad. Or you’re in a coffee shop reading on your cell phone. Or at home reading on a tablet in your armchair with a cup perched on a side table conveniently within reach.

Without looking away from the screen, you’ll sometimes reach over for the cup, grab it, and bring it to your mouth to drink. This virtually automatic, quotidian activity is actually extremely complex. In order for you automatically to grab your coffee cup and take a sip, your brain has to keep track of where your hand is, where the coffee cup is, how to move your hand to the coffee cup, how to grasp the handle of the coffee cup, and then how to move your hand — now grasping the cup — to your lips. Yet we perform these simple actions virtually without thinking!

What I’d like to focus in on is the first step of that sequence of simple actions — knowing where your hand is. That’s because a recent paper by Kazumichi Matsuyima in Scientific Reports sheds new light on what it is that our brains do in order for us to know where the parts of our body are.

Thinking about this will also allow me to review one of the most famous proofs in twentieth century analytic philosophy. And it will allow me to talk a little about one of the most discussed results in recent cognitive science. All of which will give me a chance to talk about some cool stuff that I wasn’t able to fit into my lectures for The Great Courses that were released last month — Theories of Knowledge: How to Think About What You Know. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Emrys Westacott

Just as Anteus in Greek mythology renewed his strength by touching the earth, so emigrés who live abroad often draw some sort of cultural or spiritual nourishment from returning to their roots. In my case this means returning to Britain, and specifically to the countryside that remains, for the most part, green and pleasant. Usually I do this in the summer, so it made a nice change this year to be in Britain at the beginning of Spring. The trees not yet being in leaf left more of the landscape open and visible. There were fewer flowers, of course, but there were also fewer holiday makers clogging up the roads and the honey pot tourist sites.

Just as Anteus in Greek mythology renewed his strength by touching the earth, so emigrés who live abroad often draw some sort of cultural or spiritual nourishment from returning to their roots. In my case this means returning to Britain, and specifically to the countryside that remains, for the most part, green and pleasant. Usually I do this in the summer, so it made a nice change this year to be in Britain at the beginning of Spring. The trees not yet being in leaf left more of the landscape open and visible. There were fewer flowers, of course, but there were also fewer holiday makers clogging up the roads and the honey pot tourist sites.

The British countryside, especially the Derbyshire Peak District (full disclosure–it’s where I grew up, and I’m biased), is simply fabulous for its combination of natural beauty, historical interest, scientific significance, variety and accessibility. When out walking, the superb large-scale ordinance survey maps–now available as a phone-app– are indispensable aids and do much to enhance the experience. I never fail to be amazed at how, in spite of there being over sixty-five million people crammed onto a small island, one can so easily enjoy in virtual solitude fields and hillsides, rivers and streams, woods and moorlands. One sunny afternoon I walked out onto a moor just a few miles East of greater Manchester, and in three hours met no-one. Read more »

by Shawn Crawford

Like most Kafka stories, “A Hunger Artist” inserts you into a bewildering situation, appears to offer you some solace and meaning, and then bewilders you all over again.

The Hunger Artist is just that: a man that starves himself for a living. But unlike Gregor Samsa awaking to find himself an enormous insect, this story echoes Kafka’s actual time and place (Europe from 1883-1924). Hunger artists traveled the continent, creating a craze like flagpole sitting or MMA fighting. Generally confined, guards watched over the artist to ensure he did not eat. Crowds would gather to take stock of an artist’s slow emaciation; postcards were sold with photos of the artist at his most gaunt state.

The hero of our story resides in a cage filled with straw. Children gather, clinging to each other in terror and wonder. The Artist’s handler, the Impresario, determines that forty days of fasting produces the largest crowds and peak interest before attention begins to wane. On the final day, the Artist emerges from his cage to great acclaim, angry that he cannot pursue his craft for even longer. Simply the delirium of hunger, the Impresario assures the crowd.

As the fad begins to decline, the Artist finds himself relegated to a circus, living in a cage surrounded by the show’s menagerie. But while he laments the lack of attention, he can now fast for as long as likes. He can take his art to the ultimate extreme. Spoiler alert: the artist starves himself to death. It’s Kafka after all. Read more »

Long exposure of evening scene from my balcony after a rare spring snowfall in March of 2016. The white streaks on the street are from the headlights of a car driving by; the blue ones from a speeding police car.

by Dwight Furrow

The wine world thrives on variation. Wine grapes are notoriously sensitive to differences in climate, weather and soil. If care is taken to plant grapes in the right locations and preserve those differences, each region, each vintage, and indeed each vineyard can produce differences that wine lovers crave. If the thousands of bottles on wine shop shelves all taste the same, there is no justification for the vast number of brands and their price differentials. Yet the modern wine world is built on processes that can dampen variation and increase homogeneity. If these processes were to gain power and prominence the culture of wine would be under threat. The wine world is a battleground in which forces that promote homogeneity compete with forces that encourage variation with the aesthetics of wine as the stakes. In order to understand the nature of the threat homogeneity poses to the wine world and the reasons why thus far we’ve avoided the worst consequences of that threat we need to understand these forces. I will be telling this story from the perspective of the U.S. although the themes will resonate within wine regions throughout much of the world.

The wine world thrives on variation. Wine grapes are notoriously sensitive to differences in climate, weather and soil. If care is taken to plant grapes in the right locations and preserve those differences, each region, each vintage, and indeed each vineyard can produce differences that wine lovers crave. If the thousands of bottles on wine shop shelves all taste the same, there is no justification for the vast number of brands and their price differentials. Yet the modern wine world is built on processes that can dampen variation and increase homogeneity. If these processes were to gain power and prominence the culture of wine would be under threat. The wine world is a battleground in which forces that promote homogeneity compete with forces that encourage variation with the aesthetics of wine as the stakes. In order to understand the nature of the threat homogeneity poses to the wine world and the reasons why thus far we’ve avoided the worst consequences of that threat we need to understand these forces. I will be telling this story from the perspective of the U.S. although the themes will resonate within wine regions throughout much of the world.

The modern wine world in the U.S. that began to emerge and solidify in the 1950’s was built on five pillars, all of which contributed to the remarkable quality revolution that transformed wine into a readily accessible symbol of refinement that graces even middle class dinner tables throughout the world. Those pillars include: the adoption of the French image of wine as a dry (i.e. not sweet), food friendly, nuanced aesthetic object; advances in wine technology that enabled clean, consistent wines and extracted more flavor; an increase in ripeness levels encouraged by that improved technology as well as the emergence of warm climate wine regions; and the adoption of independent standards of wine criticism that put pressure on complacent traditions to increase quality. All of this took place in a context of expanding demand and the resulting need to ramp up supply and develop more consumer friendly marketing. Read more »

by Samia Altaf

In May 2014, a young man beat his twenty-year-old sister, Farzana, to death by hitting her head with a brick. He did this in broad daylight just outside the High Court building in Lahore, the cultural, artistic and academic capital of Pakistan. He did it as local policemen and passersby looked on, lawyers in their black flowing robes went in and out of their offices and barely fifty yards away, inside the building, the bewigged and begowned Chief Justice sat with his hand on the polished gavel.

In May 2014, a young man beat his twenty-year-old sister, Farzana, to death by hitting her head with a brick. He did this in broad daylight just outside the High Court building in Lahore, the cultural, artistic and academic capital of Pakistan. He did it as local policemen and passersby looked on, lawyers in their black flowing robes went in and out of their offices and barely fifty yards away, inside the building, the bewigged and begowned Chief Justice sat with his hand on the polished gavel.

Farzana, a young woman from a lower-middle-class family, had married a man against her family’s wishes. She had come to the High Court that day to provide proof that she had married voluntarily and had not been abducted by her husband as her family claimed when they filed the case to “get her back.” Farzana was dead, the bridal henna still bright red on her hands and feet, before her case was called for hearing by the court.

Though this was one in a string of incidents of violence against women, and though many similar incidents have happened in Pakistan since, the shock and horror of the murder consumed us for a few days and became international news. On May 29, 2014, the BBC asked, “How can families do this?”

One answer to the question is that families can perpetrate violence against their daughters because they have years of practice doing so every day. Women in Pakistan live in a culture of ambient violence, and incidents of exaggerated violence labeled “honor killings” are just lamentable spikes in the ambient violence of their everyday lives. Read more »

by Anitra Pavlico

Springtime always reminds me of Johann Sebastian Bach. When I was young, my father coaxed me to go to a concert celebrating Bach’s 300th birthday. I used to think it was arcane knowledge, Bach’s date of birth, but Google recently featured it on their homepage–he would have been 334 on March 21. He belongs to everyone, even if it feels as if he is communicating to you personally. His music speaks of emotion, vitality, and renewal, which makes it fitting that his birth rings in the spring. Scholars and performers have of course written much about Bach, so I mainly would like to write about my own experiences and to comment on his Well-Tempered Clavier, two volumes of preludes and fugues in each of the keys of the scale, meant at least in part for students learning keyboard. It is much more than exercises, though; as the critic Harold Schonberg wrote, “if music does have a Bible, it is Book I of the Well-Tempered Clavier.”

There is a terrific video on YouTube of András Schiff playing Book I of the Well-Tempered Clavier live at The Proms in 2017. It is as good an accompaniment to this article as any. Even Schiff’s facial expressions tell a story about the emotion inherent in this music. Bach has sometimes been played in a dry, clinical, “sewing machine” style, as Schonberg described in his 1972 column for the New York Times to mark the Well-Tempered Clavier’s 250th anniversary. Schonberg notes, however, that Bach would not have played it that way himself: “His pupils testified that he was always interested in the emotional content of a piece — the Affekt.”

The conductor John Eliot Gardiner writes in Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven that “Bach’s keyboard works maintain a tension — born of restraint and obedience to self-set conventions — between form (which we might describe variously as cool, severe, unbending, narrow or complex) and content (passionate or intense) more palpably and obviously than does his texted music.” The Well-Tempered Clavier pieces reflect this tension, as beneath the orderly facade lies deep emotion. The first prelude of Book I, in C major, is celestial in its stillness and simplicity. At the same time, it contains near-constant striving: delicious, arpeggiated chords are ever-moving to the end goal of C major where they began. This is one to listen to when you want to believe that life is pure, simple, and good, but you suspect danger lurks under the surface. It is followed by the C minor prelude, in contrast, which is dangerous throughout. After that journey, the accompanying C minor fugue’s eventual arrival at C major is cathartic. Read more »