by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

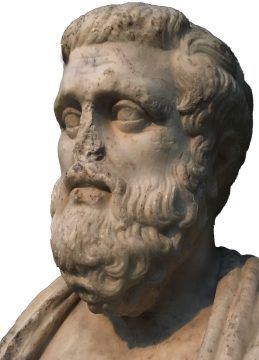

Epictetus’ Enchiridion 52 is an exercise in metaphilosophy. It captures the double-vision students of Stoicism must have about their own progress. The core insight of E52 is that the tools of philosophical inquiry and progress toward insight can themselves become impediments to progress. E52 is the last entry of the Enchiridion in Epictetus’ own words (with E53 being inspirational quotations from Cleanthes, Euripides, and Plato), and in it, a decidedly practical program is endorsed. The key to this endorsement is the contrastive case Epictetus makes. Here is E52 in its entirety:

[1] The first and most necessary subject in philosophy is the application of philosophical principles, such as ‘Don’t be a fraud’. The second is that of proofs, such as why it is that we ought not to be frauds. The third subject is that which confirms and articulates these proofs, such as, how is this a proof? For, what is a proof? What is inference? What is contradiction? What is truth? What is falsehood?

[2] Therefore, the third subject is necessary because of the second, and the second is necessary because of the first. But the most necessary and the one where we must linger is the first. Yet we do it backwards, because we devote time to the third subject and entirely busy ourselves with it, while we completely neglect the first. Consequently, we’re frauds, but we’re ready to prove that we ought not to be frauds.

The problem, of course, is the last sentence: though we have proofs we should not be frauds, we nevertheless are frauds. How, given the Stoic program of philosophical training – that we have the proofs precisely in order to remind ourselves not to be frauds – does this result come about? And more importantly, how, with these tools, can we prevent it?

In a nutshell, E52’s core argument is that because we must master logic in order to master the reasons in moral deliberation, we become distracted by the technicalities of the logic and hence neglect the primary practical objectives. The diagnosis of the problem is, we believe, part of what promises to prevent it. The upshot of the three arguments taken together is that Stoic progressors, in taking the prescribed means to their philosophical progress, stand in their own way. The point of E52 is a final reminder of this challenge arising from philosophical progress. That is, there is a particular kind of vice that is exhibited by those who are making progress toward virtue.

Think, for example, of all the occasions when a technical detail of a broader line of thought has been the point of controversy. Or consider the fact that in pursuing the wisdom in an academic literature, one becomes fixated not with the wisdom in the literature, but the literature itself. The person who obsesses over mastering the thought of some obscure thinker and devotes himself to the act of interpretation has abandoned the pursuit of the wisdom. Or take the fact that it is far too easy to confuse correctly interpreting a thinker with interpreting the thinker as correct. We as philosophy professors regularly see this phenomenon – students who become obsessed with a figure’s thought and come to treat quotation of that thinker as a way of settling philosophical questions. Epictetus, too, found it wearisome that his students were easily distracted by the allure of being scholarly interpreters of Chyrsippus, the great Stoic, but not in being those who live the philosophy:

When a man prides himself in being able to understand and interpret the books of Chrysippus, say to yourself, “If Chrysippus had not written obscurely, this man would have nothing on which to pride himself.” (E 49)

The point, of course, is that reading hard books is part of the journey of philosophical improvement. And so is mastering the finer details of logic. You have to sweat the small stuff with argument and critical dialogue, or else philosophy just dissolves into bullshit. Yet it’s not bullshit. So we must pay attention and work hard. But we should also remember that the hard work is in the service of something beyond mastering an old, dusty, and difficult book; it’s for the sake of something on the other side of a complicated set of logical rules –namely, seeing ourselves and the world aright. And then living in accordance with that well-formed vision. We do philosophy so we aren’t frauds, and yet sometimes philosophy can make us frauds.

The key is that our progress in mastering philosophy’s methods is valuable, and we should be happy with ourselves as we progress. Mastering techniques of proof, being able to interpret a thorny passage – these are indications that one’s skills are developing. And one should, with the development of important skills, feel good in those developments. The problem emerges from our pride in our progress; this can divert us from the larger project. This would not be a problem were we already wise, but we are not yet (or maybe ever) wise. We make progress toward wisdom, but that progress, when we reflect on it as those who are not wise, can itself be a distraction from the wisdom we seek. We become caught up with a detail of argumentation theory that now prevents us from thinking our way back to improving our lives. We may find ourselves lingering over and debating the interpretation of a difficult text and forget why the text matters. Those are Epictetus’ worries about those who care for philosophy – the way we learn to philosophize and pursue wisdom itself has occasion for us to be distracted by philosophy’s tools and means.

How do we avoid the problem of Enchiridion 52? Epictetus does not tell us. And we, ourselves, do not know, either. For sure, making the temptation explicit to ourselves is a step forward – knowing and naming the error is better than not having that awareness. But this knowledge is not perfect, and it does not prevent the error. In fact, it may be a feature and not a bug of philosophical progress – one is constantly waylaid by details that likely don’t matter in the long run. But if philosophy means that we sweat the small stuff in thinking things through, then that means we may be distracted by and pursue many lines of thought that ultimately just don’t matter. That’s the risk and cost of the program. So long as we are aware of the risks going in, maybe we can mitigate them.