by Shawn Crawford

Preachers at our Baptist church had to ask for an Amen. We weren’t just going to spontaneously let one loose. God can’t drive a parked car, my youth minister would say. Meaning you had to exert your own will as well in the pursuit of a righteous life. When it came to the Holy Spirit, we rarely even tried the ignition.

After the death of Christ, the apostles found themselves a pretty sorry lot. Scared and convinced they were the next candidates for execution, most went into hiding. What transformed them was not merely the appearance of the resurrected Jesus, but the gift of the Holy Spirit, and this gift came to them through the sound of a rushing wind and tongues of fire that descended from heaven and “came to rest on each of them” (Acts 2.3). The depiction of this event generally involves little candle flames hovering over the Apostles. As if that wasn’t cool enough, the first thing that happened for the Apostles was the ability to speak in languages they had never known. Which came in handy, because it just so happened Jews all over the world had gathered in Jerusalem for Pentecost, a derivation of a Greek word that means “fifty” and denoted the fiftieth day after Passover and the beginning of the next Jewish holiday Shavuot. Peter gave the first sermon on the need for repentance and baptism, the Christian church began, and the word Pentecost became associated with the Holy Spirit and speaking in tongues, which would eventually spawn a focus on such practices in Pentecostal churches. Read more »

I don’t know a lot about guns.

I don’t know a lot about guns.

Smacked my head on the pavement while jogging across campus in the rain. Had my hands on my stomach, holding documents in place underneath my shirt to keep them dry. So when my foot went out after skipping over a puddle, I couldn’t get my front paws down in time to brace my fall as I corkscrewed through the air, landing on my hip and shoulder, and whiplashing my head downward. Consequently I don’t have the brain power to crank out 2,000 fresh words. So here’s a dated piece about Baby Boomer navel gazing and ressentiment.

Smacked my head on the pavement while jogging across campus in the rain. Had my hands on my stomach, holding documents in place underneath my shirt to keep them dry. So when my foot went out after skipping over a puddle, I couldn’t get my front paws down in time to brace my fall as I corkscrewed through the air, landing on my hip and shoulder, and whiplashing my head downward. Consequently I don’t have the brain power to crank out 2,000 fresh words. So here’s a dated piece about Baby Boomer navel gazing and ressentiment.

Thirty years ago this week two million people joined hands forming a human chain across 676 kilometers of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Known as the

Thirty years ago this week two million people joined hands forming a human chain across 676 kilometers of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Known as the  I’ve just come back from a lovely vacation in Ireland. We did a lot of driving and usually had the radio on, often to RTE, the state run station (the equivalent to the BBC in the UK). At least once an hour an advertisement would come on reminding people that they need to get a TV license, which costs 160 Euros, $177 a year. I grew up in the UK, where a license is 154.50 sterling, $187 a year, and remember the ads when I was a child that warned of the TV detector van coming around and catching people who hadn’t paid their license. Of course, that was in the days of very obvious exterior antennas on houses. When TV licenses were first issued in the UK after the second world war, they funded the single BBC channel. Even when I was a child, there were only 3 channels, then when I was a teen 4, and two of those were the BBC. In the UK today, a license is needed for any device that is

I’ve just come back from a lovely vacation in Ireland. We did a lot of driving and usually had the radio on, often to RTE, the state run station (the equivalent to the BBC in the UK). At least once an hour an advertisement would come on reminding people that they need to get a TV license, which costs 160 Euros, $177 a year. I grew up in the UK, where a license is 154.50 sterling, $187 a year, and remember the ads when I was a child that warned of the TV detector van coming around and catching people who hadn’t paid their license. Of course, that was in the days of very obvious exterior antennas on houses. When TV licenses were first issued in the UK after the second world war, they funded the single BBC channel. Even when I was a child, there were only 3 channels, then when I was a teen 4, and two of those were the BBC. In the UK today, a license is needed for any device that is

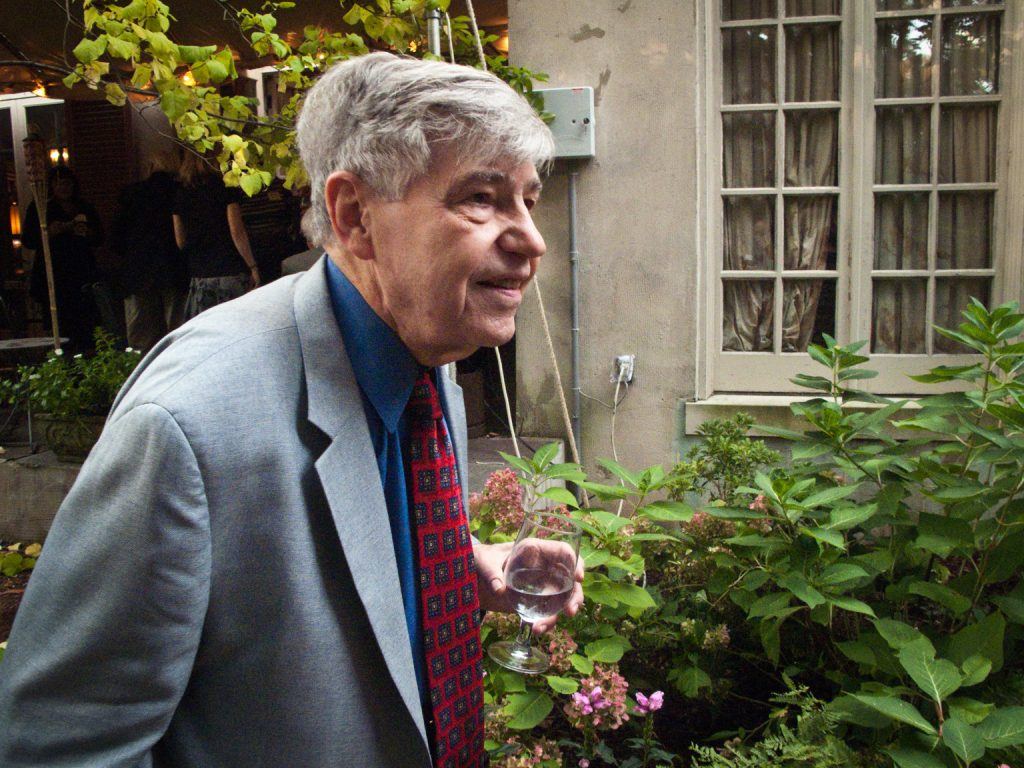

The community of philosophers is mourning the loss of Barry Stroud, one of the great philosophers of the past half-century, who died on Friday, August 9 of brain cancer. Stroud earned his B.A. from the University of Toronto and his Ph.D. from Harvard University. From 1961 he taught at the University of California, Berkeley, where I knew him during my time as a graduate student there.

The community of philosophers is mourning the loss of Barry Stroud, one of the great philosophers of the past half-century, who died on Friday, August 9 of brain cancer. Stroud earned his B.A. from the University of Toronto and his Ph.D. from Harvard University. From 1961 he taught at the University of California, Berkeley, where I knew him during my time as a graduate student there.

I live and work in two different cities; on the commute, I continuously ask my phone for advice: When’s the next train? Must I take the bus, or can I afford to walk and still make the day’s first meeting? I let my phone direct me to places to eat and things to see, and I’ll admit that for almost any question, my first impulse is to ask the internet for advice.

I live and work in two different cities; on the commute, I continuously ask my phone for advice: When’s the next train? Must I take the bus, or can I afford to walk and still make the day’s first meeting? I let my phone direct me to places to eat and things to see, and I’ll admit that for almost any question, my first impulse is to ask the internet for advice.

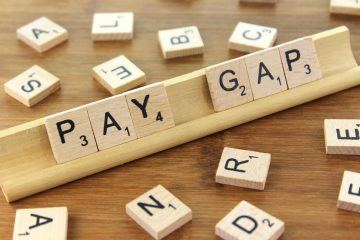

To follow the popular discourse about the gender wage gap in the United States is to confront perpetual confusion. It is a confusion created at least in part by pronouncements of the type many of us have heard: “Women are paid only 82 cents for every dollar men earn! It is high time for women to earn equal pay for equal work!” Two sentences, each true standing alone, but in juxtaposition creating the impression that the

To follow the popular discourse about the gender wage gap in the United States is to confront perpetual confusion. It is a confusion created at least in part by pronouncements of the type many of us have heard: “Women are paid only 82 cents for every dollar men earn! It is high time for women to earn equal pay for equal work!” Two sentences, each true standing alone, but in juxtaposition creating the impression that the  On occasions, while meandering the various English countryside and woodland paths, I have been pleasantly surprised to come across anglers. I have met fishermen dangling their lines in either a pond in some remote corner of the low-lying areas, or wading in water and casting a line down through the waters of a gently flowing river.

On occasions, while meandering the various English countryside and woodland paths, I have been pleasantly surprised to come across anglers. I have met fishermen dangling their lines in either a pond in some remote corner of the low-lying areas, or wading in water and casting a line down through the waters of a gently flowing river.