by Brooks Riley

by Brooks Riley

by Chris Horner

To become mature is to recover that sense of seriousness which one had as a child at play. —Nietzsche

Freud is supposed to have claimed that the two key things for happiness in life are work and love. If he did, he should have added a third: play. It’s this that Nietzsche is referring to in the quotation above. The aphorism states a paradox: we are told that to be ‘mature’ (whatever that is) we must return to playing like we did as a child. And what to make of that ‘sense of seriousness’ in a child’s play? Surely Nietzsche is thinking of the complete absorption and focus that a child is supremely capable of experiencing. If we are lucky we can recall times in our childhood when we were completely lost in the thing we were doing, seeing or hearing: serious play. As adults this can all too often elude us. It can seem a thing belonging to the lost time of childhood. But we should not give up the quest for it: it is a key to joy in life.

But let’s not idealise or sentimentalise the child. Children are in fact often intolerant of frustration, easily bored and keen to get shiny new stuff. And adults really can learn important habits of discipline and perseverance that children find so irksome. But they are also capable, to a degree that many adults find difficult, of the opposite of all that. A distinction needs to be made between childish and childlike. With the former we have all the characteristics associated with immaturity: a tendency to be easily distracted or bored, the urge for immediate gratification, demand for toys, and so on. All characteristics, incidentally, that our society tends to encourage in the adult. One of the key features of our time, surely, is divided attention, distraction and the promotion of multi-tasking. We even have an ‘attention economy’ in which corporations compete to distract us. And we know about the twitchy addiction to the smartphone and to social media. But all this hyperactivity, this constant busyness, can actually block us from attending to what is important. A drifting, distracted attention actually narrows our focus, because it thinks it knows what it wants, that it is looking for ‘something interesting’. It stays one step ahead of boredom – for a while.

To be childlike is quite different. Read more »

by Anitra Pavlico

It is difficult nowadays not to be mindful of how ubiquitous the mindfulness movement has become. A Fortune article from 2016 described meditation as a “billion-dollar business”: “From Bridgewater’s Ray Dalio and Salesforce’s Marc Benioff to Goldman Sachs traders and Google programmers, Big Business loves meditation.” This is perhaps reason enough to stay away from it, or at least to stay away from anything that charges you money to do something that you can easily do for free–namely, sit and do nothing. But a surprising number of observers have pointed to other shortcomings or even dangers in meditation and mindfulness practices.

There have been so many articles on the incredible benefits of meditation (which I’ll use interchangeably with mindfulness) that you come to feel you’re putting yourself in harm’s way by not doing it. As Masoumeh Sara Rahmini wrote recently in The Conversation, however, citing a study published in Perspectives on Psychological Science, “scientific data on mindfulness is limited . . . Studies on mindfulness are known for their numerous methodological and conceptual problems.” She notes that the journal PLOS ONE retracted a meta-analysis of mindfulness, citing concerns over methodology as well as undeclared financial conflicts of interest. Rahmini also takes issue with the Westernized version of Buddhism that is sold to modern mindfulness practitioners–one that is divorced from centuries of Buddhist tradition. She credits, or blames, Jon Kabat-Zinn, among others. Kabat-Zinn, the founder of the popular Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program offering mindfulness training to help with stress and pain, has argued that the MBSR technique contains the “essence” of Buddhism, which he says is universal and supported by science.

The trouble is that what used to be a spiritual practice, supported by a framework of teachings and in an organized setting, with spiritual guides, is now a definition-less practice, unmoored from tradition, lacking a scaffolding in case you should trip, devoid of a philosophy. Read more »

by Tim Sommers

Unfortunately, you have a brain tumor. You don’t know it yet. Your doctor doesn’t know it yet. But you are beginning to have symptoms. The tumor is pressing on surrounding brain tissue and causing you develop a number of delusional beliefs. You believe you are the best swimmer in the world. You believe that dogs and cats are aliens. You believe that you invented the apostrophe. You also, as it happens, believe that you have a brain tumor.

Unfortunately, you have a brain tumor. You don’t know it yet. Your doctor doesn’t know it yet. But you are beginning to have symptoms. The tumor is pressing on surrounding brain tissue and causing you develop a number of delusional beliefs. You believe you are the best swimmer in the world. You believe that dogs and cats are aliens. You believe that you invented the apostrophe. You also, as it happens, believe that you have a brain tumor.

So, you have a brain tumor. You believe you have a brain tumor. And the cause of your believing that you have a brain tumor is the brain tumor that you have. So, when the doctor diagnosis you with a brain tumor, are you entitled to say, “I know, right!”?

If the belief that you have a brain tumor is caused by the same thing that causes you to believe you invented the apostrophe, I think most of us would say that you don’t, in fact, know that you have a brain tumor – even if you believe it and it’s true. But it’s difficult to see why. It has something to do, probably, with justification.

Implicitly or explicitly philosophers, epistemologists to be more specific, define knowledge as justified true belief. Knowledge, then, is a kind of belief. What kind? Well, of course, the belief has to be true to count as knowledge. But it also has to be justified. If you correctly guess what the weather will be like tomorrow, we shouldn’t say that you knew it. If you predict the weather accurately using instruments and satellite maps, then you may have had or have knowledge. The brain tumor example raises questions about how justification works. There’s something wrong with the connection the belief has to why you believe it. It echoes an even more famous puzzle – the Gettier problem. Read more »

by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

“Taxi to Bethlehem, taxi to Jericho!” the man at a tourism kiosk is shouting, as I make my way from the tram to Jaffa Gate, known also as Hebron Gate, to Muslims as “Bab al Khalil,” or “door of the friend,” named after Hebron where the prophet Ibrahim/Abraham (Khalil al Allah “God’s Friend”) is laid to rest. Of significance too, is the association of this gate with King David’s (prophet Dawud’s) chamber, for followers of the three Abrahamic faiths: the crusaders named it “King David’s Gate.” It is one of the seven main stone portals of the walled city of Jerusalem.

“Taxi to Bethlehem, taxi to Jericho!” the man at a tourism kiosk is shouting, as I make my way from the tram to Jaffa Gate, known also as Hebron Gate, to Muslims as “Bab al Khalil,” or “door of the friend,” named after Hebron where the prophet Ibrahim/Abraham (Khalil al Allah “God’s Friend”) is laid to rest. Of significance too, is the association of this gate with King David’s (prophet Dawud’s) chamber, for followers of the three Abrahamic faiths: the crusaders named it “King David’s Gate.” It is one of the seven main stone portals of the walled city of Jerusalem.

To reach the street level at the train station in Jerusalem, one must take four escalators up, three of them vertiginously long. I’m reminded that this is the city of ascensions: miracles associated with Abraham, Jesus and Muhammad. The ancient, sacred expanse, rises up as an invisible, vertical cityscape. Jerusalem’s silhouette is cast in the worshippers’ perception of the heavens— avenues in the air— leading to a divine promise. The tragedy of the spirit agonizing to make peace with God as it barters peace with fellow-humans, is more raw here than anywhere else. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

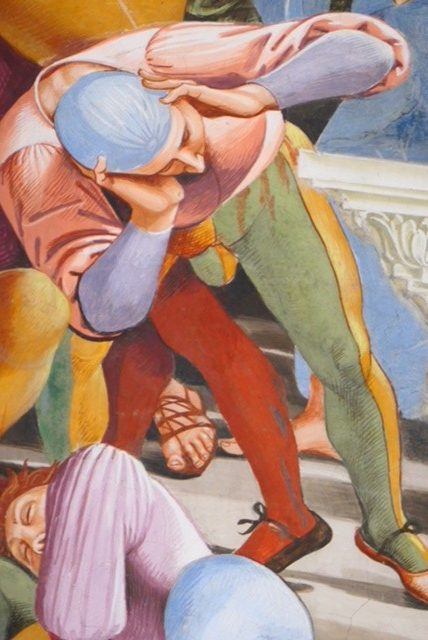

It’s not every day that a small, unexpected masterpiece shows up in your mailbox, arriving with the same modest ‘ping’ that announces the other electronic missives. This was no ordinary masterpiece. It was the photograph of a detail from Luca Signorelli’s fresco La Fine del Mondo on the entrance wall of La Cappella di San Brizio in Orvieto, the work itself a masterpiece of painterly skill and imagination, dating from ca.1500. It was taken by a good friend who spent several days with the monumental Signorelli frescoes on the interior walls of the cathedral of Orvieto.

The masterpiece I received, one small element of the arched fresco, achieved its rarified aesthetic status from having been isolated by the photographer for the frame, an act of proto-cropping used by anyone who’s ever put his eye to a viewfinder—or for that matter, anyone who’s ever opened his eyes.

We are all born with a cropping tool: It’s called focus. When we wake up in the morning, the eyes flutter open, we leave our cerebral home with its latent, chimerical images and are confronted by a giant canvas with millions of details, fuzzy around the outer edges, stretching out a full 180 degrees. Without a thought, we begin to cut away the dull bits, homing in on the alarm clock, the window, our phones, a doorknob, maybe even our fingernails. This is how we maneuver our way through the day and through life, cropping the big picture to highlight the parts we actually need to see at any given moment. Most of our time and attention are devoted to the details we’ve cropped from our greater field of vision, whether it’s the utensils we use, or the paths we take, or the signs we read.

In photography, cropping occurs before the picture is taken. Read more »

by Joseph D. Martin and Marta Halina

Calls for a Manhattan Project–style crash effort to develop artificial intelligence (AI) technology are thick on the ground these days. Oren Etzioni, the CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, recently issued such a call on The Hill. The analogy is commonly used to describe DeepMind’s initiative to build artificial general intelligence (AGI). It is similarly used to describe military initiatives to build AGI. At a conference last year, DARPA announced a $2 billion investment in AI over the next five years. Ron Brachman, former director of DARPA’s cognitive systems initiative, said at this conference that a Manhattan Project is likely needed to “create an AI system that has the competence of a three-year old.”

Calls for a Manhattan Project–style crash effort to develop artificial intelligence (AI) technology are thick on the ground these days. Oren Etzioni, the CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, recently issued such a call on The Hill. The analogy is commonly used to describe DeepMind’s initiative to build artificial general intelligence (AGI). It is similarly used to describe military initiatives to build AGI. At a conference last year, DARPA announced a $2 billion investment in AI over the next five years. Ron Brachman, former director of DARPA’s cognitive systems initiative, said at this conference that a Manhattan Project is likely needed to “create an AI system that has the competence of a three-year old.”

In one sense, the goals of such analogies are clear. AI, the comparison implies, has the potential to be as transformative for our society as nuclear weapons were in the mid-twentieth century. Whoever masters it first will enjoy a massive head start on the next wave of technological development, economic competition, and, yes, the arms race of the twenty-first century. It’s a project that comes with ethical implications that demand focused and well-resourced attention. These consequences are so important that we should not bat an eye at ploughing limitless resources into its development.

But if this analogy is to sustain such a bold claim, it bears closer scrutiny. First, analogies of this sort are not innocuous. Invocations of historical examples, especially examples so iconic as the Manhattan Project or the Apollo program, aim to borrow the authority—and implications of success—that such historical episodes command. It is prudent to examine analogies to see if that authority is merited, or if it has been unjustly swiped. Read more »

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

Mathematics and music have a pristine, otherworldly beauty that is very unlike that found in other human endeavors. Both of them seem to exhibit an internal structure, a unique concatenation of qualities that lives in a world of their own, independent of their creators. But mathematics might be so completely unique in this regard that its practitioners have seriously questioned whether mathematical facts, axioms and theorems may not simply exist on their own, simply waiting to be discovered rather than invented. Arthur Rubinstein and Andre Previn’s performance of Chopin’s second piano concerto sends unadulterated jolts of pleasure through my mind every time I listen to it, but I don’t for a moment doubt that those notes would not exist were it not for the existence of Chopin, Rubinstein and Previn. I am not sure I could say the same about Euler’s beautiful identity connecting three of the most fundamental constants in math and nature – e, pi and i. That succinct arrangement of symbols seems to simply be, waiting for Euler to chance upon it, the way a constellation of stars has waited for billions of years for an astronomer to find it.

The beauty of music and mathematics is that anyone can catch a glimpse of this timelessness of ideas, and even someone untrained in these fields can appreciate the basics. The most shattering intellectual moment of my life was when, in my last year of high school, I read in George Gamow’s “One, Two, Three, Infinity” about the fact that different infinities can actually be compared. Until then the whole concept of infinity had been a single concept to me, like the color red. The question of whether one infinity could be “larger” than another sounded as preposterous to me as whether one kind of red was better than another. But here was the story of an entire superstructure of infinities which could be compared, studied and taken apart, and whose very existence raised one of the most famous, and still unsolved, problems in math – the Continuum Hypothesis. The day I read about this fact in Gamow’s book, something changed in my mind; I got the feeling that some small combination of neuronal gears permanently shifted, altering forever a part of my perspective on the world. Read more »

by Emily Ogden

Fans are the people who know the quotes, the dates of publication, the batting averages, the bassist on this album, the team that general manager coached before. I am not a fan. Don’t get me wrong. I’m full of enthusiasms. But I can’t match you statistic for statistic. I haven’t read the major author’s minor novel. I don’t care who the bassist was. You win. I’m an amateur.

Fans are the people who know the quotes, the dates of publication, the batting averages, the bassist on this album, the team that general manager coached before. I am not a fan. Don’t get me wrong. I’m full of enthusiasms. But I can’t match you statistic for statistic. I haven’t read the major author’s minor novel. I don’t care who the bassist was. You win. I’m an amateur.

Amateur gets opposed to professional sometimes: the amateur isn’t making money from her skill or her knowledge. Other times, amateurism gets opposed to expertise: amateurs screw it up, experts fix it. These are not the meanings I intend. In French, an amateur is a lover; fan, a nineteenth-century US coinage, comes from fanatic. The amateur leaves some space for ignorance, letting the relationship to the beloved thing—the sports team, the artwork—retain the quality of an affair. The fan, in the particular sense I mean, gets lumbered under facts. There is something of the jealous monogamist about fandom, something of the checker for digital traces of the beloved’s secret life. Who hasn’t been there? But wouldn’t it be better if we hadn’t? When I say I am not a fan, I mean I aspire not to follow out that particular impulse. I aspire not to compete, at the cocktail party, for possession of Herman Melville, as measured in knowledge of his vital statistics.

Ownership of the beloved object is tempting but it’s not the shiniest prize that fandom holds out to you. The greatest temptation is a credential, a badge: you know all these things, so you must not be dumb. I’ve flashed that badge plenty, even if it would have been better not to. Read more »

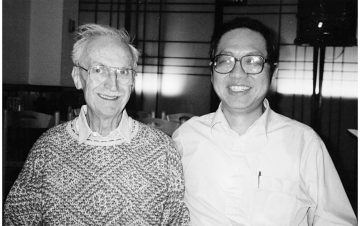

Azra Raza, author of the forthcoming book The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last, oncologist and professor of medicine at Columbia University, and 3QD editor, decided to speak to 26 leading cancer investigators and ask each of them the same five questions listed below. She videotaped the interviews and over the next months we will be posting them here one at a time each Monday. Please keep in mind that Azra and the rest of us at 3QD neither endorse nor oppose any of the answers given by the researchers as part of this project. Their views are their own.

1. We were treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with 7+3 (7 days of the drug cytosine arabinoside and 3 days of daunomycin) in 1977. We are still doing the same in 2019. What is the best way forward to change it by 2028?

2. There are 3.5 million papers on cancer, 135,000 in 2017 alone. There is a staggering disconnect between great scientific insights and translation to improved therapy. What are we doing wrong?

3. The fact that children respond to the same treatment better than adults seems to suggest that the cancer biology is different and also that the host is different. Since most cancers increase with age, even having good therapy may not matter as the host is decrepit. Solution?

4. You have great knowledge and experience in the field. If you were given limitless resources to plan a cure for cancer, what will you do?

5. Offering patients with advanced stage non-curable cancer, palliative but toxic treatments is a service or disservice in the current therapeutic landscape?

A nationally-recognized authority on leukemia, Dr. Guido Marcucci has lectured around the world and authored more than 270 scholarly papers on the subject. His ultimate goal is to make leukemia a thing of the past. He has received numerous competitive NCI grants for his clinical and research work focused on the pathogenesis, treatment and prognostic assessment of patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Dr. Marcucci currently serves on the editorial board of three journals, including Blood and the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

by Mary Hrovat

When I watched the 2019 documentary on Apollo 11, it carried me back not to the summer of 1969, when it happened, but to the mid-1980s, when I was an undergrad. I was eight when Apollo 11 launched; of course I was aware of the space program and the moon landings, but I don’t have any memories of everyone gathering around to watch those first steps on another world. My parents weren’t particularly interested, and I don’t remember being caught by the spirit of the times myself.

When I watched the 2019 documentary on Apollo 11, it carried me back not to the summer of 1969, when it happened, but to the mid-1980s, when I was an undergrad. I was eight when Apollo 11 launched; of course I was aware of the space program and the moon landings, but I don’t have any memories of everyone gathering around to watch those first steps on another world. My parents weren’t particularly interested, and I don’t remember being caught by the spirit of the times myself.

It wasn’t until shortly before I began an undergraduate program in astrophysics, in the mid-1980s, that I started to take a serious interest in space exploration. I read everything I could find on the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs; I was particularly interested in first-hand accounts by the astronauts themselves. Carrying the Fire, by Michael Collins, still stands out in my mind as the very best of these.

I was gripped by the idea of being out in space and seeing Earth from space or the moon from orbit. Sometimes when I was out at night under a dark starry sky, I thought about Collins’s descriptions of his solo passes behind the moon, during which he was out of contact with Earth. I imagined seeing the blackness of space and untwinkling stars out one window of the spacecraft and the impenetrable darkness of the moon in shadow out the other. Read more »

by Claire Chambers

Today I ask to what extent it is a positive development that there are no discussions of race and religion in Danny Boyle’s and Richard Curtis’s film Yesterday, whose protagonist Jack Malik is from a South Asian, possibly Muslim, background.

In his essay ‘Airports and Auditions’ for Nikesh Shukla’s The Good Immigrant, the actor Riz Ahmed outlined three stages of  cinematic representations of Muslims. Stage One features stereotyped figures (the taxi driver, terrorist, cornershop owner, or oppressed woman). Stage Two involves a portrayal that subverts and challenges those stereotypes. Finally, Stage Three is ‘the Promised Land, where you play a character whose story is not intrinsically linked to his race’. Does Yesterday reach that Promised Land or fall short? I examine the film’s depiction of Jack Malik, whose race and religion are irrelevant to this story about love, fame, the music industry, and the Beatles.

cinematic representations of Muslims. Stage One features stereotyped figures (the taxi driver, terrorist, cornershop owner, or oppressed woman). Stage Two involves a portrayal that subverts and challenges those stereotypes. Finally, Stage Three is ‘the Promised Land, where you play a character whose story is not intrinsically linked to his race’. Does Yesterday reach that Promised Land or fall short? I examine the film’s depiction of Jack Malik, whose race and religion are irrelevant to this story about love, fame, the music industry, and the Beatles.

Building on Riz Ahmed’s work, in 2017 two researchers, Sadia Habib and Shaf Choudry, developed the Riz Test for Muslims’ depictions in film and television. Inspired by Ahmed’s speech to the House of Commons about the power and harm of media representations, Habib and Choudry created their own version of the famous Bechdel Test for cinematic portrayals of women. They asked some key questions about the cinematic portrayals of Muslims:

If the Film/ TV Show stars at least one character who is identifiably Muslim (by ethnicity, language or clothing) – is the character:

- Talking about, the victim of, or the perpetrator of terrorism?

- Presented as irrationally angry?

- Presented as superstitious, culturally backwards or anti-modern?

- Presented as a threat to a Western way of life?

- If the character is male, is he presented as misogynistic? Or if female, is she presented as oppressed by her male counterparts?

If the answer for any of the above is Yes, then the Film/ TV Show fails the test.

This test has already been hugely influential in the world of television, with Channel 4’s new Head of Drama Caroline Hollick (herself of Trinidadian descent, pictured) arguing at 2019’s Bradford Literature Festival that it should be uppermost in the mind of anyone commissioning programmes about Muslims. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Joan Harvey

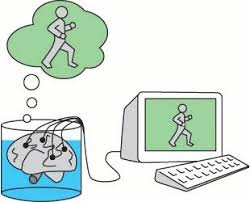

Our expectations sculpt neural activity, causing our brains to represent the outcomes of our actions as we expect them to unfold. This is consistent with a growing psychological literature suggesting that our experience of our actions is biased towards what we expect. —Daniel Yon

Our expectations sculpt neural activity, causing our brains to represent the outcomes of our actions as we expect them to unfold. This is consistent with a growing psychological literature suggesting that our experience of our actions is biased towards what we expect. —Daniel Yon

Because consciousness is something common to all of us, it is also interesting to many of us, though we may lack both philosophical and scientific backgrounds. And while many regular people are interested to some degree in the workings of their mind, those who have experimented with drugs and meditation may be even more curious about the latest research. From a fairly young age I’ve had a fair amount of experience with both psychedelics and meditation, though certainly not consistently through my life. And, for a while, I had separate conversations with two different persons—one heavily into psychedelics and one a longtime Zen practitioner—about some of the general books on consciousness.

Among the three of us, our biases sometimes came to the fore. Andy Clark’s book on predictive processing has a very sexy title—Surfing Uncertainty–and some very difficult, academic text—my Zen friend found it unreadable, and attributed this to the fact that Clark is not a meditator. My friend, in turn, had me read some recent books on consciousness with a Buddhist bias, which I disliked for their slanted view (though I have had a regular meditation practice at times). Of course the psychedelic expert liked Michael Pollen’s book How to Change your Mind, as did we all. And we all particularly liked Thomas Metzinger’s The Ego Tunnel. Though not much discussed in the book, perhaps Metzinger’s background in both meditation and psychedelics unconsciously played into our appreciation. We could relate to his ideas of conscious experience as a process and a tunnel through reality, as well as his discussion of transparency, the name he gives for the way we are unaware of the medium through which information reaches us. All of us were (the Zen practitioner has since died) atheist materialists (though also all familiar with plenty of ecstatic, mystical, and irrational states which we felt had a purely physical basis), and intuitively Metzinger’s position made sense to us. The “ego tunnel,” as Metzinger says, is a complex property of the neural correlates of consciousness, the “neurofunctional properties in your brain sufficient to bring about a conscious experience.” He also locates out-of-body experiences and other related phenomena squarely in the physical, as opposed to metaphysical, world.

But my beloved grandmother was a Freudian psychoanalyst, and due to her (and alone in my family, and among most of my friends) I became interested in Freud. Read more »

by Marie Gaglione

Into the Woods

Into the WoodsMost college students would readily submit that there are any number of external forces that inhibit their ability to perform or engage meaningfully with their academic endeavors, even when there is a genuine motivation and desire to do so, although such drives are often compromised by more compelling opportunities (see: survivor hour and other fun! college! activities!). There’s life outside of the university to contend with; relationships end, grandparents die, dads go to jail (the last one is particularly case-specific, but statistics on students with parents in prison would be an interesting metric to have). The necessary reaction to all of these things, for those students who have the means to carry on, is to carry on. These events can be managed, more or less, with the passage of time and the support of the community, in whatever sense of the word. There are Things One Can Do to move on from Hard Times.

I am no stranger to these external forces. Since I’ve been an undergrad, I’ve had partners become exes, I’ve lost my grandmas, I’ve been told over text of far too serious things. It’s an eerie dimension of the modern era that one can read of a friend’s suicide or a father’s prison time via instant message. We bounce from one screen to another in our waking hours and we pretend like Alexa isn’t recording our every word. Every day we let Google know our thoughts, our questions, our hopes, our fears; every day we feed into the ultimate hive mind, an unlimited data collective. We’re living in Bradbury’s fever dream with a heightened dose of Orwellian anxiety. And it’s the world today (in conjunction with certain childhood traumas and genetic predispositions) that contributes to what I’ve found far more difficult to overcome than the Hard Times: the internal forces.

The two ages I oscillate between when considering how long I’ve been depressed are seven and fifteen. At 22, that just means I’ve been depressed for either amount of time. I think about what qualifies as the true beginning – was it the cookie-cutter childhood I missed? Or the chemical dependency that’s kept me prisoner since high school? Was it when I first contemplated the unsustainable and toxic nature of capitalism, and does it get worse the more I study the climate patterns? Whatever the answer may be, the fact remains that a lot of the time I am sad (or worse – sad and panicked). And this isn’t said in an attempt to garner pity or gain sympathy because I’m being vulnerable – it’s the reality of my experience. And it’s relevant here, in a nature essay, because it’s what brought me to the white deer; it’s what made me abandon my car and belongings and head, without intention or explanation, into the woods. Read more »

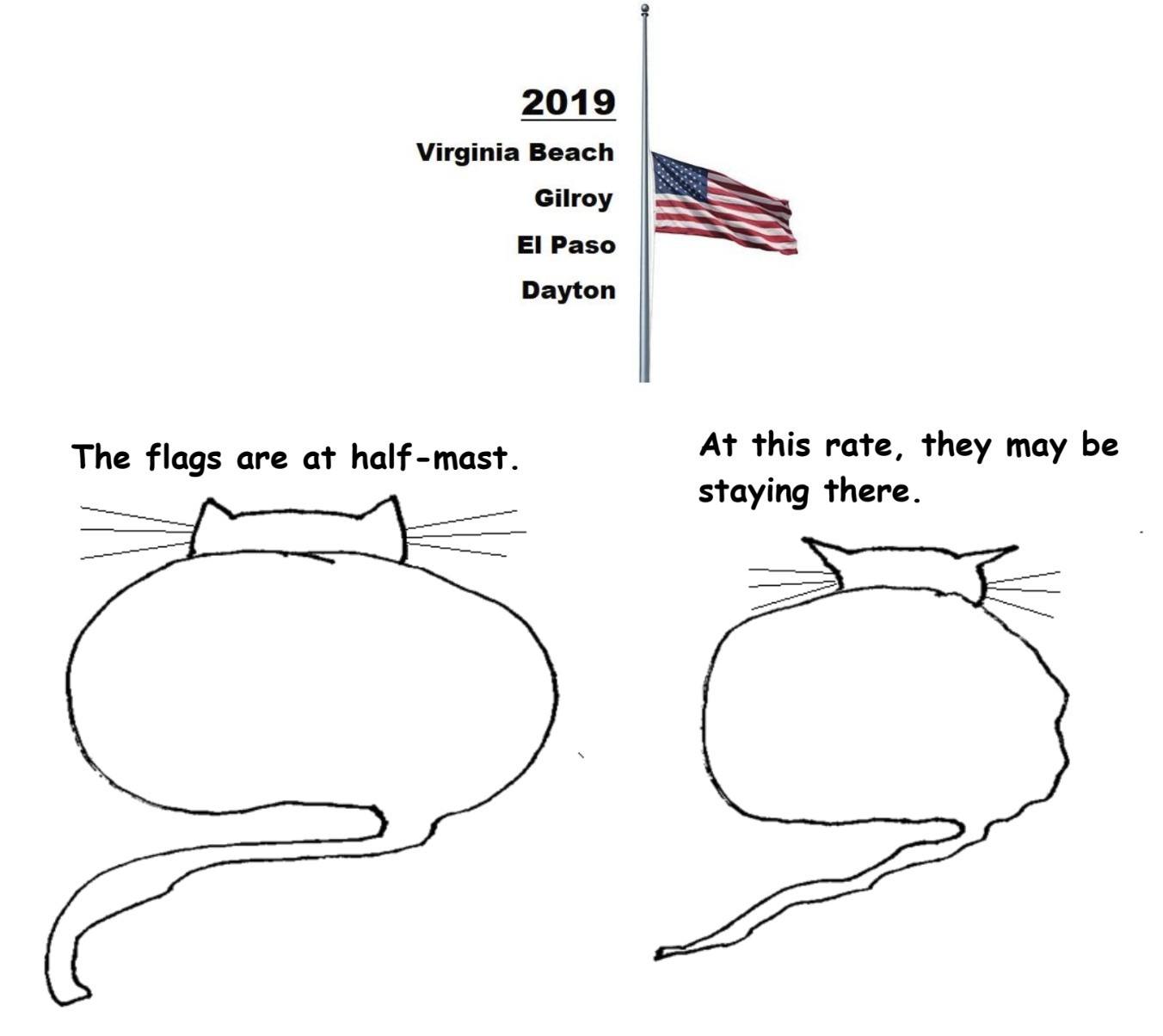

Our cat, Frederica Krüger, has taken to spying on me while I work in my home office.

by Thomas O’Dwyer

The first real work of art I ever saw was Auguste Renoir’s Les Parapluies. I was a teenager, and the painting had arrived in Dublin following a 1959 agreement between the governments of Ireland and Britain. This they had signed to solve an arts wrangle as tortuous as the Greek Elgin Marbles saga. The Renoir was part of a collection bequeathed to Ireland by Sir Hugh Lane. A Cork-born art collector, Lane died on board the Lusitania, which a German torpedo sank off the coast of Ireland in 1915. His collection of 39 paintings include works by Manet, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, Morisot, and Degas. He had first left his collection to London’s National Gallery, but it was later found that he had attached a codicil to the will. It stated that he had changed his mind and wanted his paintings to stay in Dublin. The addendum was signed but not witnessed, and the London gallery declared legal ownership.

The dispute roused Irish nationalist passions, already at fever point in the fight for independence. Hugh Lane’s aunt was Lady Gregory, a patron of W.B. Yeats. They led Ireland’s cultural elites in a campaign to honour Lane’s last wishes. The governments renegotiated the 1959 agreement in 1993, and it comes up for renewal again this year. The new accord divided the paintings into two groups. London restored 31 of the pictures to Dublin, and every six years the cities trade the remaining eight, Les Parapluies among them. Read more »

by Gabrielle C. Durham

My friend does not use punctuation when he texts, so there is a stream-of-consciousness quality to much of his communications. According to the fine folks at Buzzfeed, you would likely infer that he is a millennial, but that is not true. He conveys his points while eschewing syntactic finality fairly clearly, so when he does use punctuation, he makes a big deal of it, as in “Look. At. The. Punctuation. I’m. Using.”

My friend does not use punctuation when he texts, so there is a stream-of-consciousness quality to much of his communications. According to the fine folks at Buzzfeed, you would likely infer that he is a millennial, but that is not true. He conveys his points while eschewing syntactic finality fairly clearly, so when he does use punctuation, he makes a big deal of it, as in “Look. At. The. Punctuation. I’m. Using.”

According to this article, using ending punctuation (specifically a period) in a text can convey insincerity (by way of gratuitous formality) or anger due to code-switching. That sounds a little forced to me, but I’m a Gen Xer, so I do not fit in the classification of folks who are deemed to be responsible for killing half the industries your parents relied on utterly.

Punctuation, which comes from the Latin root punctatio for making a point from the verb pungere, which means to pierce (circa 1539), is the set of standardized symbols in every language, and the marks do vary, that clarify meaning by separating phrases, clauses, and sentences as well as by adding breathing cues. Pablo Picasso described punctuation marks as “the fig leaves that hide the private parts of literature.” The standard punctuation marks in English are period, question mark, exclamation point, comma, colon, and semicolon. Read more »