Robert Freeman. Abundant Life, 2019.

Oil on canvas.

Thanks to Laura Weinstein for connecting us!

by Chris Horner

In my years in education I have regularly come across what I call the lightbulb fallacy: the view that people have degrees of brightness and that it is the job of education to measure the wattage of learners in order to find the best social sockets to plug them into. It is a noxious idea. The notion that intelligence is a measurable ‘something’ that is possessed by people in varying degrees is one of the ways in which we end up with an education system that fails the majority of those it is supposed to be helping. It damages not just those in schools and colleges but people in general, and it is based on a fallacy about what it is to learn and understand.

One can see a number of reasons why adopting a notion like this would seem useful for an education system like ours: if people have amounts of intelligence that can be identified and measured, then people can be classified and fitted into the place in education, and later in the economy, that will suit their degree of ‘brightness’. But the problem is that people aren’t like lightbulbs with differing degrees of wattage, and this essentialising approach, that imputes a fundamental, intrinsic trait to an individual, leaves most people experiencing education as a demotivating process in which they learn to experience themselves as failures. Examinations put the seal on this by placing students in an ascending hierarchy of brightness. The effect of this on many, if not most, learners is unhelpful, to put it mildly. As an educator I have had to deal with numerous situations in which students have in effect used this as an alibi for giving up, since if those other students are brighter than oneself, why bother? Of course, not every learner reacts to lower marks in that way – but most get the message, in the end, that they cannot get far up the ladder of educational achievement, and that success is the preserve of a small number of the very bright. Read more »

Wadih Arap is the Director of the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey at University Hospital and Chief, Division of Hematology/Oncology in the Department of Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School. He has served on the National Cancer Institute’s Board of Scientific Counselors, several review boards for the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Defense’s Prostate and Breast Cancer Research Program. His research is based on the premise that differential protein expression in disease tissues enables the development of novel, targeted drugs to treat human disease. By integrating genomic analyses and analytical high-throughput technology, functional protein-protein interactions can be manipulated to develop clinical strategies for effective disease management.

Azra Raza, author of the forthcoming book The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last, oncologist and professor of medicine at Columbia University, and 3QD editor, decided to speak to more than 20 leading cancer investigators and ask each of them the same five questions listed below. She videotaped the interviews and over the next months we will be posting them here one at a time each Monday. Please keep in mind that Azra and the rest of us at 3QD neither endorse nor oppose any of the answers given by the researchers as part of this project. Their views are their own. One can browse all previous interviews here.

1. We were treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with 7+3 (7 days of the drug cytosine arabinoside and 3 days of daunomycin) in 1977. We are still doing the same in 2019. What is the best way forward to change it by 2028?

2. There are 3.5 million papers on cancer, 135,000 in 2017 alone. There is a staggering disconnect between great scientific insights and translation to improved therapy. What are we doing wrong?

3. The fact that children respond to the same treatment better than adults seems to suggest that the cancer biology is different and also that the host is different. Since most cancers increase with age, even having good therapy may not matter as the host is decrepit. Solution?

4. You have great knowledge and experience in the field. If you were given limitless resources to plan a cure for cancer, what will you do?

5. Offering patients with advanced stage non-curable cancer, palliative but toxic treatments is a service or disservice in the current therapeutic landscape?

by Anitra Pavlico

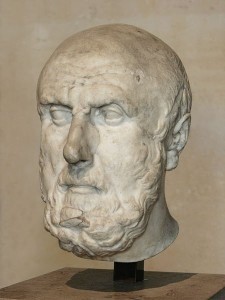

Most of the modern revival of Stoicism has centered on the works of Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius–all from the “Late Stoa,” or the third phase in the history of Stoicism. No complete works survive from either the early or middle period.

Chrysippus (c. 279-206 B.C.E.) was one of the most influential early Stoics. He studied with Cleanthes, who studied directly with Zeno, who founded the school in 262 B.C.E. You won’t see his quotes on any inspirational desktop art, but Chrysippus was perhaps the one most responsible for keeping Stoicism alive in its early years. A later Stoic saying was, “If Chrysippus had not existed, neither would the Stoa.”

Chrysippus was prolific, having reportedly written over 705 books. No single book remains, and today we only have around 475 fragments. He was the second great logician, after Aristotle. Diogenes Laertius reported in his Lives of the Philosophers that most people believed that if the gods were to pursue dialectic, they would adopt Chrysippus’ system alone. The seemingly airtight logic of many Stoic approaches to life, as they have filtered down to us, stems directly from Chrysippus. The Stoic philosophy featured three branches: logic, physics, and ethics. The scope of logic also included the analysis of argument forms, rhetoric, grammar, propositions, perception, and thought. [1] Josiah Gould points out that Chrysippus felt that logic should be studied before the other two branches of the philosophy. [2] While Gould notes that it is lamentable that we do not have a single full logic treatise when they have such “tantalizing” titles as On Negative Propositions, An Introduction to the Study of Ambiguity, On Imperatives, and Reply to Those Who Think that a Proposition Can be Both False and True, he maintains that we can reconstruct some of his views based on the fragments we possess. Read more »

by Elizabeth S. Bernstein

In 1973 Betty Friedan traveled to France to have a conversation about the state of feminism with Simone de Beauvoir, whom she regarded as a cultural hero. Friedan’s own opinions had evolved considerably in the decade since the publication of The Feminine Mystique. She would elaborate those changes sometime later in a new book, The Second Stage, in which she argued for women’s work in the home to be viewed as “real work” and included in the gross national product. Now, in her meeting with Beauvoir, Friedan asked her opinion on ways to recognize the value of that work, such as crediting it for social security purposes, or distributing vouchers which parents could either use to buy childcare or collect on themselves as full-time caregivers. Perhaps Friedan wondered if Beauvoir’s thinking too might have changed since she stated in The Second Sex that the work of a woman at home “is not directly useful to society, it does not open out on the future, it produces nothing.” If so, she got her answer: Beauvoir, holding out for a total remake of society, believed that even in the meantime “No woman should be authorized to stay at home to raise her children …. Women should not have that choice, precisely because if there is such a choice, too many women will make that one.”

Rhetoric is one thing, and given the many ideological variations within the women’s movement, any attempt to attribute to it some particular position on women’s work in the home would almost certainly invite fierce disagreement. But it is much harder to dispute what has actually happened in the last half-century. In certain respects the women’s movement has had enormous success. Women’s levels of education, employment, and income have all surged. In that sense the situations of men and women are far more alike than they once were. Through their inroads into realms previously closed to them, women have obtained a share of the status which was once conferred far more heavily on men.

I would be hard-pressed to say, though, that there has been any improvement in the status of “women’s work.” (I mean by that the traditional work of women, whether performed by women or by men.) The essential functions without which no society can exist – the care of children, the preparation of food, the keeping of a house, the care of the elderly and infirm – continue to be devalued. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Niall Chithelen

Drive the laneless roads of Lanzhou, sit the high-speed train, and then you are in the center of Tongwei county, a city among ancient villages, covered in construction works, ground floors of sliding glass storefronts, signs of green, blue, red, or black, with yellow or white lettering. And yet nothing shines here; this is not a colorful place.

A man who seems to be helping to organize your travel in the area met you at the train station and he reappears at lunch. You are not sure who he is, but he knows people here. He answers the phone with a gust of air.

A local museum sits behind a heavy locked door on the third floor of a building which is otherwise unremarkable and quite short on windows. Some artifacts in the museum are thousands of years old, some are hundreds. Also on display are two posters from the 1930s, written haphazardly by young members of the Red Army, messages to the “ordinary people” in the area. The tour guides are expert and excited. When you leave, they close the door again and lock it. The last group of visitors was days ago.

The landing outside the museum is lit only by a sign of dry red light. A young child wanders around the museum, stands on the landing, wary of the visitors. His attention is focused on a phone screen, and, watching him walk in front of the sign unfazed, you wonder if his memories too will bear the darkness of this building, hued red around their edges. Read more »

by Andrea Scrima

Tragedies like the mass shootings in El Paso, Dayton, and most recently (since this panel first aired last month) in Odessa bring everything to a stop. As we read the details and look at the pictures, we all pause, look around, and take stock of our priorities and what we hold dear. Writers are no different, except for the work we do. We’re often in the middle of describing a particular part of the world—when another part is suddenly falling apart.

Jon Roemer and David Winner polled a handful of active writers and asked how public tragedies impact their current and future work—projects that may or may not portray mass shootings. We aimed to gauge how writers deal with such landmark events in practical ways and how, if at all, their writing engages with violence in America.

QUESTION 1

In The New Yorker last year, Masha Gessen described the difficulty of defending the values and institutions currently under attack, because it requires “preserving meanings” and is “the opposite of imagination.” She aspired to “find a way to describe a world in which… imagination is not only operant but prized and nurtured.” On Facebook the Monday after the shootings in Dayton and El Paso, a different writer, Grant Faulkner, simply posted two words—“another killing”—over and over, hundreds of times. Gessen described traditionally crafted work, while the Facebook post is visceral and immediate. Where do you think your next work will land?

ANSWERS:

Jon Roemer: The Facebook post reflects what I was feeling the Monday after the shootings. But the fiction I’m writing now probably won’t be read for a year or more. So I think hard about its relevance, especially if we keep rushing toward more violence. Part of the job is to be forward-thinking. Just wish I could write and publish faster.

Zachary Lazar: I’m writing the most traditional novel of my life right now (though that isn’t saying much). I simultaneously have no faith in the power of novels and total commitment to the novel as a thing, an art form, something I like. Mass shootings seem to me to be one symptom among many of our culture’s failure to address meaninglessness, to create meaning, and even though I don’t believe there is such a thing as meaning, the active pursuit of it is essential to sanity. I just don’t give a shit about social media. I guess it did good work during the Arab Spring but I think the role it plays in the U.S. right now is more or less comparable to the crack epidemic of the ’80s and ’90s. It makes TV look nourishing. Read more »

Reflection in a hotel window in Vahrn, South Tyrol, in September of 2017. The slight confusion this photo creates about what is inside and what outside the window reminded me of some lines from the beginning of the poem “Pale Fire” by Vladimir Nabokov (in the eponymous novel which it begins, the poem is supposed to have been written by the fictional character John Shade) in which he so beautifully describes a similar scene of window reflections:

I was the shadow of the waxwing slain

By the false azure in the windowpane;

I was the smudge of ashen fluff–and I

Lived on, flew on, in the reflected sky.

And from the inside, too, I’d duplicate

Myself, my lamp, an apple on a plate:

Uncurtaining the night, I’d let dark glass

Hang all the furniture above the grass,

And how delightful when a fall of snow

Covered my glimpse of lawn and reached up so

As to make chair and bed exactly stand

Upon that snow, out in that crystal land!

by Tim Sommers

John Rawls, the author of “A Theory of Justice” and “Political Liberalism”, was the most important political philosopher of the twentieth-century – and the most influential. His theory of justice, “justice as fairness”, and, much later, his theory of political legitimacy via the free use of “public reason”, transformed philosophy and provided the most systematic, comprehensive normative political theory since Utilitarianism more than a century earlier. He was (and is) widely read by lawyers, economists, and public policy makers. He was on Vaclav Havel’s bookshelf during the Velvet Revolution. His theory of civil disobedience, not Thoreau’s or Gandhi’s, “The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy” describes as “the most widely accepted”. He was the foremost liberal egalitarian – arguing that while we all have certain rights, freedoms, and liberties that the state cannot violate, in a just society the least well-off members should be as well-off as possible – even while, outside of the academy, liberal politics splintered into right neoliberalism and left identity-politics. He trained two generations of moral philosophers who went on to dominate the field. To this day, in any survey of the most important, or most cited philosophers of the twentieth-century, he is consistently in the top five – and is always the most highly-ranked moral philosopher.

I was lucky enough to be a student in the last class Rawls taught as a full professor in 1991 and to be in touch on-and-off for a few years after. Many, many people knew him much better than I did. And nothing I say about his views relies solely on any private conversations I had with him. But, like so many people his life touched, I was deeply affected not only his intellect, but his dignity, his warmth, his generosity, and his humility. So, full disclosure, I don’t pretend to be objective on the subject of Rawls. Read more »

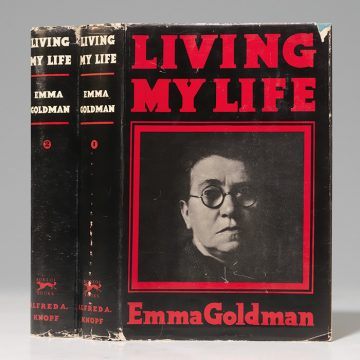

by Adele A Wilby

In a political era where many of the ‘isms’ in radical politics: Marxism, socialism, communism, anarchism, Trotskyism have either been discredited or have lost their appeal and force in western democracies, I found it refreshing to visit the life of one individual deeply involved in shaping those radical movements in the twentieth century: the anarchist, Emma Goldman, in her autobiography Living My Life.

In a political era where many of the ‘isms’ in radical politics: Marxism, socialism, communism, anarchism, Trotskyism have either been discredited or have lost their appeal and force in western democracies, I found it refreshing to visit the life of one individual deeply involved in shaping those radical movements in the twentieth century: the anarchist, Emma Goldman, in her autobiography Living My Life.

The politics of ‘Red Emma’ as she came to be known, brought much controversy to Goldman over the course of her life: she was loved by many and equally hated and vilified for a politics that, in essence, aimed at, what she considered, would promote the well-being of humanity. ‘Anarchism,’ she wrote in her essay ‘Anarchism: What it Really Stands For’, ‘…stands for the liberation of the human mind from the dominion of religion; the liberation of the human body from the dominion of property; liberation from the shackles and restraint of government…for a social order based on free grouping of individuals for the purpose of producing real social wealth…anarchism is the philosophy of the sovereignty of the individual’. Great ideals! However, conceptualising ‘anarchism’ in such terms suggests a tension between collective interest and well-being, and the individual, a tension not fully resolved in her writing. But as Goldman was to realise over the course of five decades of political activism, the zeal behind her political ideals often resulted in the corruption of those good intentions and were the source of disappointment and nefarious practices, as exemplified in a kindred ideology, ‘socialism’, during Russia in the early twentieth century.

Nevertheless, despite the idealism within the political philosophy of anarchism, Goldman and other thinkers like her, such as her mentor Peter Kropotkin, and her life-long colleague and friend, Alexander Berkman, left a political legacy that is worthy of critical attention. Read more »

by Pranab Bardhan

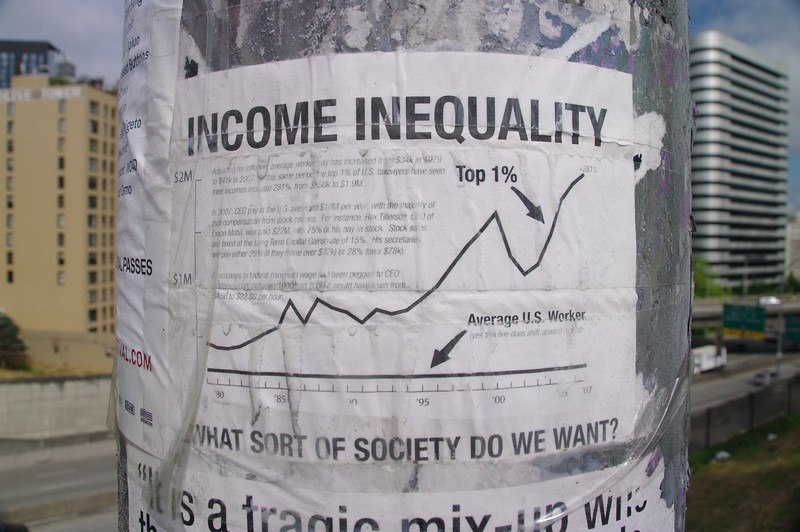

There is widespread concern about increasing or high economic inequality in many countries, both rich and poor. At a global level, according to the World Inequality Report 2018, the richest 1% in the world reaped 27% of the growth in world income between 1980 and 2016, while bottom 50% of the population got only 12%. Over roughly the same period, however, absolute poverty by standard measures has generally been on the decline in most countries. By the widely-used World Bank estimates, in 2015 only about 10 per cent of the world population lived below its common, admittedly rather austere, poverty line of $1.90 per capita per day (at 2011 purchasing power parity), compared to 36 per cent in 1990. This decline is by and large valid even if one uses broader measures of poverty that take into account some non-income indicators (like deprivations in health and education) for the countries for which such data are available.

There is widespread concern about increasing or high economic inequality in many countries, both rich and poor. At a global level, according to the World Inequality Report 2018, the richest 1% in the world reaped 27% of the growth in world income between 1980 and 2016, while bottom 50% of the population got only 12%. Over roughly the same period, however, absolute poverty by standard measures has generally been on the decline in most countries. By the widely-used World Bank estimates, in 2015 only about 10 per cent of the world population lived below its common, admittedly rather austere, poverty line of $1.90 per capita per day (at 2011 purchasing power parity), compared to 36 per cent in 1990. This decline is by and large valid even if one uses broader measures of poverty that take into account some non-income indicators (like deprivations in health and education) for the countries for which such data are available.

If absolute poverty is declining, while measures of relative inequality (of income or wealth) show a significant rise (or remain very high), this implies that the conditions of the poor may be improving, but those for the rich may be improving much more. But if people are less poor than before, should we be concerned about high or rising inequality, about how much better-off the rich are, and, if so, why? This is an important question on which more clarity is needed, as quite often when people tell you why they dislike inequality many of the examples they cite are really about their aversion to the stark poverty around them. Read more »

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

For me, a highlight of an otherwise ill-spent youth was reading mathematician John Casti’s fantastic book “Paradigms Lost“. The book came out in the late 1980s and was gifted to my father who was a professor of economics by an adoring student. Its sheer range and humor had me gripped from the first page. Its format is very unique – Casti presents six “big questions” of science in the form of a courtroom trial, advocating arguments for the prosecution and the defense. He then steps in as jury to come down on one side or another. The big questions Casti examines are multidisciplinary and range from the origin of life to the nature/nurture controversy to extraterrestrial intelligence to, finally, the meaning of reality as seen through the lens of the foundations of quantum theory. Surprisingly, Casti himself comes down on the side of the so-called many worlds interpretation (MWI) of quantum theory, and ever since I read “Paradigms Lost” I have been fascinated by this analysis.

For me, a highlight of an otherwise ill-spent youth was reading mathematician John Casti’s fantastic book “Paradigms Lost“. The book came out in the late 1980s and was gifted to my father who was a professor of economics by an adoring student. Its sheer range and humor had me gripped from the first page. Its format is very unique – Casti presents six “big questions” of science in the form of a courtroom trial, advocating arguments for the prosecution and the defense. He then steps in as jury to come down on one side or another. The big questions Casti examines are multidisciplinary and range from the origin of life to the nature/nurture controversy to extraterrestrial intelligence to, finally, the meaning of reality as seen through the lens of the foundations of quantum theory. Surprisingly, Casti himself comes down on the side of the so-called many worlds interpretation (MWI) of quantum theory, and ever since I read “Paradigms Lost” I have been fascinated by this analysis.

So it was with pleasure and interest that I came across Sean Carroll’s book that also comes down on the side of the many worlds interpretation. The MWI goes back to the very invention of quantum theory by pioneering physicists like Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger. As exemplified by Heisenberg’s famous uncertainty principle, quantum theory signaled a striking break with reality by demonstrating that one can only talk about the world only probabilistically. Contrary to common belief, this does not mean that there is no precision in the predictions of quantum mechanics – it’s in fact the most accurate scientific framework known to science, with theory and experiment agreeing to several decimal places – but rather that there is a natural limit and fuzziness in how accurately we can describe reality. As Bohr put it, “physics does not describe reality; it describes reality as subjected to our measuring instruments and observations.” This is actually a reasonable view – what we see through a microscope and telescope obviously depends on the features of that particular microscope or telescope – but quantum theory went further, showing that the uncertainty in the behavior of the subatomic world is an inherent feature of the natural world, one that doesn’t simply come about because of uncertainty in experimental observations or instrument error. Read more »

Mohandas Narla, D.Sc. is Vice President for Research of New York Blood Center and has authored 340 peer-reviewed publications and 100 review articles and book chapters. His research focuses on red cell physiology and pathology; helping improve understanding of the molecular and structural basis for red cell membrane disorders, developing mechanistic insights into pathophysiology of thalassemias and sickle cell anemia, characterizing structural and functional changes induced in red cells by the malarial parasite, plasmodium falciparum and understanding of erythropoiesis particularly on disordered erythropoiesis in Diamond-Blackfan Anemia and Myelodysplasia. Dr. Narla has been a member of numerous NIH review and advisory panels for the last 30 years and is currently on the editorial boards of numerous journals including Journal of Biological Chemistry, Biochemistry, and Current Opinion in Hematology.

Azra Raza, author of the forthcoming book The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last, oncologist and professor of medicine at Columbia University, and 3QD editor, decided to speak to more than 20 leading cancer investigators and ask each of them the same five questions listed below. She videotaped the interviews and over the next months we will be posting them here one at a time each Monday. Please keep in mind that Azra and the rest of us at 3QD neither endorse nor oppose any of the answers given by the researchers as part of this project. Their views are their own. One can browse all previous interviews here.

1. We were treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with 7+3 (7 days of the drug cytosine arabinoside and 3 days of daunomycin) in 1977. We are still doing the same in 2019. What is the best way forward to change it by 2028?

2. There are 3.5 million papers on cancer, 135,000 in 2017 alone. There is a staggering disconnect between great scientific insights and translation to improved therapy. What are we doing wrong?

3. The fact that children respond to the same treatment better than adults seems to suggest that the cancer biology is different and also that the host is different. Since most cancers increase with age, even having good therapy may not matter as the host is decrepit. Solution?

4. You have great knowledge and experience in the field. If you were given limitless resources to plan a cure for cancer, what will you do?

5. Offering patients with advanced stage non-curable cancer, palliative but toxic treatments is a service or disservice in the current therapeutic landscape?

by Jeroen Bouterse

Have you ever been in this situation where you had to get a group of 3 men and their sisters across a river, but the boat only held two and you had to take precautions to ensure the women got across without being assaulted?

Have you ever been in this situation where you had to get a group of 3 men and their sisters across a river, but the boat only held two and you had to take precautions to ensure the women got across without being assaulted?

This problem is one of 53 puzzles in the oldest extant puzzle book in the Western (Latin) tradition: the Propositiones ad acuendos iuventes or problems to sharpen the young. Its authorship is uncertain but it is often and plausibly attributed to Alcuin, who possibly sent them to the Frankish ruler Charlemagne in 800 AD.[1] I hope you will allow me a brief introduction of these puzzles, before I go on to do what I hope will by then be redundant, namely spelling out why I think you should be thrilled by their existence.

Slugs and Pigeons

Alcuin’s puzzles are diverse, but puzzles of the same type often show up more than once. For example, some have us figure out a number based on a multiple of it, provided in a somewhat convoluted manner: a man seeing a certain number of horses and wishing that he possessed that number, and then that number again, and then a quarter more than that, for then he would possess a hundred horses (puzzle 4). There are questions that effectively ask how often a given area fits into another given area, how items can be distributed in discrete quantities given certain conditions, or how long it will take for one animal to overtake another or to cover a given distance. The first puzzle, for instance, has a leech invite a slug over for lunch, only to have us realize that it will take the poor creature centuries to get to its destination. Read more »

by Joan Harvey

If you can get the old voting against state-subsidized healthcare, and the poor voting in favor of cuts to inheritance tax, then democratic capitalism really is workable after all. —Malcolm Bull

As the objective view of the world recedes, it is replaced by intuition as to which way things are heading now. —William Davies

Life is short, and I’ve shortened mine /in a thousand delicious, ill-advised ways,/a thousand deliciously ill-advised ways —Maggie Smith “Good Bones”

Mark Twain, in his wonderful Letters from the Earth, nails the essence of human unreason. It’s not just the creation story with a talking snake, but how man has conceived of heaven, at least in Christianity.

[H]e has imagined a heaven, and has left entirely out of it the supremest of all his delights, the one ecstasy that stands first and foremost in the heart of every individual of his race—and of ours—sexual intercourse!

It is as if a lost and perishing person in a roasting desert should be told by a rescuer he might choose and have all longed-for things but one, and he should elect to leave out water!

A singing, harp-playing heaven is, as Twain points out, like the most boring church service ever, and for eternity. Yet this was the creative fantasy the main religion of the West landed on, and people for years somehow bought it. (The Islamic version is perhaps closer to what Twain had in mind, but still an extraordinarily shabby version of the imagined possible). If people are going to imagine an afterlife, not only could they be having sexual intercourse as much as they want with whoever they want with no negative consequences, but they could easily take it farther, giving themselves many more sex organs and erogenous zones and pleasures that put orgasms to shame. (I’m sure science fiction writers have gone there with no problem). Throw in some great powder skiing for me between bouts in the sack, and no knee pain. And for those who don’t like sex or don’t want it all the time, let heaven be whatever they like, endless gourmet meals with no weight gain, fantastic chess matches in Turkish baths, conversation with their philosopher heroes, horseback riding on perfect steeds. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Joshua Wilbur

This month I’m submitting a guest post written by an acquaintance of mine.

His name, strange as it may sound, is One-Week Man. He suffers from an unusual quirk: he can only remember the most recent week of his past, and he can only imagine one week into his future. He is forever stuck in this ever-shifting window of time.

One-Week Man is a bizarre, parochial soul, and I’m skeptical of his capacity to hold a well-informed opinion on anything of consequence. Nevertheless, he insisted on sharing his thoughts, which I present below, unedited.

It’s true. I can only recall one week of the past and think ahead one week into the future. (Maybe “Two-Week Man” would be a more fitting name, but I didn’t have much of a choice in the matter.)

Some explanation might be helpful. I’m writing this on a Sunday, September 1st. Exactly one week ago, I spent the day on the beach. What happened in my life prior to that sunny afternoon, I couldn’t tell you: it’s all a haze. Looking forward to next Sunday, I’m planning to do some work around the house, a one-bedroom cottage that I don’t remember moving into. Beyond that, I literally cannot imagine what the future holds. August 25th and September 8th represent the limits of my mental universe.

As it turns out, I’m very busy this week. My calendar—who would I be without it?—is filled with work meetings, doctors’ appointments, even an out-of-state conference from Wednesday to Friday. I work in the life insurance industry; I always have as far as I can tell.

For the most part, I’m content with things, despite my temporal malady. The doctors can’t explain my condition, which they consider untreatable and “psychosomatic” (whatever that means, I’ve forgotten), so there’s nothing I can do but live one week at a time. Most people, apparently, are terrible at thinking about the future. For me, it’s an absolute black hole. It’s difficult because I really do care about the fate of, well, everything: myself, my country, my planet. But I can’t see beyond the week, cursed as I am with a short-sighted brain and countless things-to-do. This is my dilemma. Read more »

by Mary Hrovat

Last weekend, a bat got into my house somehow. I first heard it in the small hours of Friday night as it scratched around somewhere near the furnace flue. I didn’t know if it was an animal settling into a new home in my attic, or if perhaps it was going out periodically to get food and bringing it back to feed babies in an established nest. All became clear very late the next night, when the bat managed to get out of the enclosure around the flue and then exit the closet where the furnace is. After some drama that I need not recount here, it flew out the front door, and I stopped gibbering on my front walk and went back inside.

Last weekend, a bat got into my house somehow. I first heard it in the small hours of Friday night as it scratched around somewhere near the furnace flue. I didn’t know if it was an animal settling into a new home in my attic, or if perhaps it was going out periodically to get food and bringing it back to feed babies in an established nest. All became clear very late the next night, when the bat managed to get out of the enclosure around the flue and then exit the closet where the furnace is. After some drama that I need not recount here, it flew out the front door, and I stopped gibbering on my front walk and went back inside.

The thing is, I don’t dislike bats. I enjoy seeing them in the evening sky. I worry about white-nose syndrome. I want there to be bats in the world, and now that I’ve had time to calm down, I’m glad the bat in my house got safely away. I can see that the experience was more stressful and life-threatening for the bat than for me. But I don’t really want bats anywhere near my house.

I was upset in large part simply because wild animals don’t belong in the house, period. But after a conversation with a friend about the bat situation at my house, I began to think about the fact that my love for and appreciation of nature is selective. I know that humans are having an appalling effect on the lives of other animals, and there’s no possible justification for our destructiveness. Yet, although I’m grateful for the presence of a fair amount of the urban wildlife around me, I wish some of it weren’t there. On some level, I’m not sure I’d mind if it were gone. Read more »