by Brooks Riley

For someone who spent most of his life trying to get on Page Six, (the New York Post’s iconic gossip column), hitting Page One was pay dirt for Donald Trump. Now that he’s there, he means to stay there, devouring our attention for the foreseeable future. One could even argue that all his lies and deplorable actions are motivated by a single, sorry ambition, to be the center of attention at all times and in all places. Outrage sells.

For someone who spent most of his life trying to get on Page Six, (the New York Post’s iconic gossip column), hitting Page One was pay dirt for Donald Trump. Now that he’s there, he means to stay there, devouring our attention for the foreseeable future. One could even argue that all his lies and deplorable actions are motivated by a single, sorry ambition, to be the center of attention at all times and in all places. Outrage sells.

Outrage is also tiresome. Trump Outrage Fatigue set in long ago, but we still can’t ignore him. Or can we? If the fate of the world wasn’t at stake we would have dropped this guy long ago from our field of vision.

I’m spending more and more time off the grid of mainstream news coverage. There are other stories out there to excite us, to outrage us or to move us. I haven’t left the grid altogether. I do keep up. But my mind now homes in on stories at the bottom of the internet page, or the seemingly trivial fillers that pepper the meal of misery at the top. Here’s a small sample:

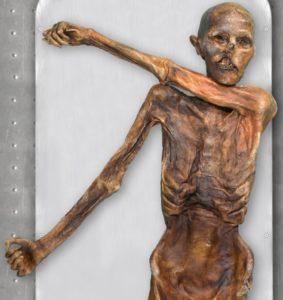

Ötzi’s Last Meal

What could be more important than the contents of Ötzi’s stomach? Certainly not the Big Mac wending its way through our leader’s digestive system. I’m not being facetious here. Ötzi is the gift that keeps on giving, ever since the 5300-year-old man who lay buried in ice for millennia was discovered by tourists in 1991 in the Ötztal Alps bordering Austria and Italy. Since then I have followed every gripping new revelation about Ötzi—what he wore, what he carried with him, how he was murdered. Ötzi is a time capsule spilling forth impossible secrets about life in the Copper Age. Now that his stomach has been found, lurking shriveled under his lungs, we know that his last meal was a hefty portion of ibex fat—not the meat itself but the subcutaneous fat that would help him withstand the bitter cold and give him endurance at high altitudes. According to a researcher, ibex meat tastes okay, but ibex fat tastes awful, so that the act of eating it must have been prophylactic, derived from some knowledge of survival strategies.

While it’s unlikely that Ötzi himself came to this information empirically, somebody did—his father, a neighbor, an ancestor. Someone figured out, possibly by dissecting the ibex, that some form of protection against the elements could be gained from the kind of fat layer between the body and the skin. Ötzi could have confirmed this empirically, through his own experience. Then again, the ibex fat, like bacon, might have been easier to carry for a man on the run, like a protein bar for modern millennials on the go.

Empiricism is fundamental to science, especially the natural sciences. It is also the powerhouse that drives every young child finding his way in the world. A mother may warn her child not to touch a hot stove. But the child may also learn the hard way, empirically, when he touches the stove. Infants put all manner of objects in their mouths, this too a kind of empirical process of discovering the properties of an object. Empiricism light.

As a solitary child, I applied my own empirical techniques to solving the conundrums around me. When a school friend suffered a serious allergic reaction in the proximity of poison ivy, I decided to experiment on myself. Finding a cluster of it behind the barn, I tore off the leaves and rubbed them onto my legs from my knees to the ankles just to see what would happen. Suffering for science, I did get a nasty case, but at no time was I ever sick. Seen from today’s perspective, I probably did my immune system a favor. And I learned that one child’s discomfort is another child’s life-threatening event.

Ötzi’s way of life undoubtedly included folk medicine, a slow-motion form of empiricism handed down the generations. In addition to grains, berries and goat meat from an earlier meal, Ötzi’s stomach also contained bracken, a poisonous fern, possibly ingested to treat his worms. The empirical reasoning here might have been: If bracken can kill a man, it can also kill worms. Dosage is everything. Ötzi didn’t die of bracken poisoning, he bled to death from an arrow shot into his shoulder.

Most of us get our information from formal empirical studies that have narrowed down the mysteries of our physical world over the centuries with rigorously structured experimentation and documentation. But mysteries are like molehills in a lawn, crush one, and two more will pop up nearby. Even in today’s highly sophisticated field of immunological therapies against cancer, the unexpected can occur, sending researchers off in a new direction to explore a medical windfall—another new mystery, another new molehill.

With Ötzi, possibly the most probed human being that has ever lived, new discoveries raise new mysteries. Like science itself, he is full of contradictions that cannot yet be explained. Here’s what we know: He was 45 when he died. He has 17 living relatives in the region. His DNA contains Neanderthal genes but also genes found on Sardinia, the island off southern Italy, far from the Alps. The type of helicobacter pylori in his gastrointestinal tract is found only in certain populations in India. He was lactose-intolerant, had atherosclerosis and may have had Lyme disease.

Narratively speaking, his story is rich with dramatic potential. Blood found on his arrowheads belonged to other humans, suggesting that his murder might have been an act of revenge for his own crimes. Or was this just a local war between villages? No empirical method will never uncover the answers to this mystery.

Next on the Ötzi agenda is the Holy Grail of modern biology—his microbiome. Could it yield secrets that might apply to our own dietary, digestive and immunological needs? If so, he may end up being one of the most important men who ever lived–and he’s not even orange, more like copper. Stay tuned.

Where am I?

The geographical ignorance of many Americans is old news. Google the question if Americans are taught geography in school, and the answer is a parochial yes: the geography of one’s own state and in some cases, one’s own country—that’s it. Jimmy Kimmel, the late-night host who regularly exposes the man-on-the-street’s ignorance about our political system or people in the news, has now come up with a geographical question so simple that it’s impossible to believe that anyone could fail to come up with an answer: Can you name a country? See for yourself.

What does it say about a person who doesn’t know where he is in this world? Geography provides a spatial context without which we are merely the center of our own tiny universe, like bees in a hive or ants in an ant hill. Without geography, we are, to paraphrase George W. S. Trow, living Within the Context of No Context. Xenophobia thrives on not knowing the difference between men from the Middle East and men from Mars. Ignorance of geography renders people incapable of relativizing their existence into something greater than themselves or extrapolating about common interests. A place on a map is much more than that: It provides proof of others who share our planet. It tells us where we come from and where we want to go. It evokes our empathy for experiences that are shared and those that are not shared. It fires our imagination.

People in ancient times could be forgiven for not knowing where they were in the world because the world was not yet measured or mapped. For them the world consisted of the terrain they traversed over a lifetime, nothing more. Ötzi’s world may have been only 30 square kilometers, but back then, it’s all he needed to know. Now, thousands of years later, in an era of global interdependency, there are still people who know only the 30 square kilometers they live in—and the rest be damned.

Chill

I’m a sucker for animal videos, so it’s no surprise that I fell for this one—of a man playing Bach and Schubert on the piano for an old blind elephant. What did surprise me is that it brought tears to my eyes, and I’m not sure why. Does it matter if the elephant appreciates what she’s hearing? In the end, we see what we want to see, in this case the quiet grace of two creatures occupying the same frame and the same soundtrack somewhere on the planet—gratifying the anthropomorphic yearning for shared experience between the species. I only wish he could have played this music for Ötzi.

More on Ötzi’s stomach here.