by Brooks Riley

by Brooks Riley

by Dwight Furrow

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists went so far as to call wine writers “bullshit artists”. (The feeling is mutual.)

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists went so far as to call wine writers “bullshit artists”. (The feeling is mutual.)

Even the sommelier-trained author of the bestselling book Cork Dork, Bianca Bosker, has reservations about the accuracy of such language. After taking writers to task for using terms such as “sinewy” and “broad-shouldered” she writes: “It seems possible that what we “taste” in a fine wine isn’t so much its flavor as the qualities of good taste that we hope it will impart to us.” She seems to be suggesting that wine writers just make stuff up to sound impressive.

The general objection is that these descriptors are metaphorical and are therefore too subjective and ambiguous to give readers an accurate, verbal portrayal of the wine. However, these complaints are tilting at windmills. Read more »

by Akim Reinhardt

Stuck is a weekly serial appearing at 3QD every Monday through early April. The Prologue is here. The table of contents with links to previous chapters is here.

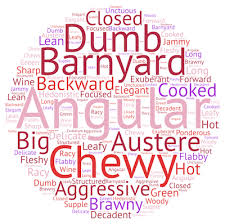

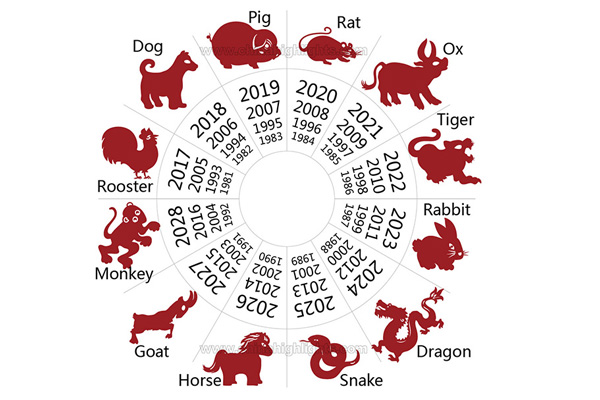

In the Chinese calendar, 2015 was the year of the sheep. I’m a sheep, and I briefly got into it. When you’re a sheep, you gotta own it.

In the Chinese calendar, 2015 was the year of the sheep. I’m a sheep, and I briefly got into it. When you’re a sheep, you gotta own it.

Ain’t no rat gonna cut you no slack.

While singing the praises of sheep and trying to hold my own against dragons, snakes and the like, I made a passing reference to the 1977 pop hit “Year of the Cat” by Al Stewart. Didn’t hear the song, didn’t sing it to myself, didn’t even utter the words. Merely wrote Al Stewart’s “Year of the Cat” in a blog post. And that, apparently, is all it took for the song to get stuck in my head.

Why did “Year of the Cat” trap me with such ease? Possibly because it’s one of the very first songs I ever purchased.

The first two long playing, vinyl record I ever bought were a couple of collections called Music Machine and Stars. It was 1979. I was eleven and a half years old. Both albums were put out by a company called K-Tel.

The brainchild of a Winnipeg, Manitoba knife salesman, K-Tel hit it big in the 1960s by taking to the airwaves and hawking various of odds and ends with an intense but simple “As Seen on TV” sales pitch. They started with all sorts of knives and bladed devices like the Veg-O-Matic and the Dial-O-Matic. It slices, it dices, bla bla bla. Other gadgets that wouldn’t make you bleed soon followed. But during the 1970s, the company was best known for music compilations.

It actually began in 1966 with a record called 25 Great Country Artists Singing their Original Hits. That format, a compilation of hit singles by various artists, was still fairly novel, and K-Tel struck gold when combining it with their high octane TV marketing formula. By the time I picked up my two discs, K-Tel had issued over 500 different albums, mostly collections. Read more »

by Eric J. Weiner

The allure of fresh and true ideas, of free speculation, of artistic vigor, of cultural styles, of intelligence suffused by feeling, and feeling given fiber and outline by intelligence, has not come, and can hardly come, we see now, while our reigning philosophy is an instrumental one. —Randolph Bourne

Schoolteachers across the grades are responsible for teaching their students how to write. Their essential pedagogical role is instrumental. With particular attention paid to format, grammar, spelling, and syntax, students ideally learn to write what they know, think, or have learned. It matters little if the student is in a class for “creative writing” or “composition,” writing is taught and practiced as a way to record thoughts, compose ideas in a coherent manner, and clearly communicate information. A student’s writing is then assessed for how well she adhered to these instrumental standards while the teacher is assessed for how well she adhered to the standards of instrumental teaching.

Schoolteachers across the grades are responsible for teaching their students how to write. Their essential pedagogical role is instrumental. With particular attention paid to format, grammar, spelling, and syntax, students ideally learn to write what they know, think, or have learned. It matters little if the student is in a class for “creative writing” or “composition,” writing is taught and practiced as a way to record thoughts, compose ideas in a coherent manner, and clearly communicate information. A student’s writing is then assessed for how well she adhered to these instrumental standards while the teacher is assessed for how well she adhered to the standards of instrumental teaching.

By contrast, writing to learn re-conceptualizes our relationship to writing from measurable outcomes to critical/creative processes. It moves the epistemological needle from instrumentality to exploration, innovation, imagination, and discovery. Writing to learn supports the development of what Randolph Bourne (1917) called “poetic vision.” Having poetic vision diverts our “creative intelligence” away from “the machinery of life” and redirects our “creative desires” toward enhancing the quality of life. “It is the creative desire,” Bourne writes, “…that we shall need if we are ever to fly” (from Twilight of Idols). Read more »

by John Schwenkler

What is the point of being courteous, kind, and otherwise well-mannered?

I suspect that most of us are inclined toward an answer that parallels Thrasymachus’ view of justice in the early books of Plato’s Republic. For Thrasymachus, what really matters to us where questions of justice are concerned is all on the side of self-interest. We care about justice in others only to the extent that it brings benefits to us and our friends, and we care about embodying justice in our own lives only to the extent that justice wins us friends, while unjust action carries the risk of punishment and social sanction. The attractiveness of this view comes out in Plato’s famous retelling of the myth of Gyges: given the power to act either justly or unjustly without being detected by others, any of us would choose the life of total injustice. In themselves, the demands of justice are at odds with the desires of naked self-interest, and the only thing that motivates us to respect them is the fear of what will happen to us if we don’t.

An analysis along these lines is even more attractive in connection with the traditional demands of courtesy. Many of us will have the sense that there is — or at least could be — something objectively, universally wrong with stealing, lying, murdering, or imprisoning a person without proper cause. By contrast, no such status accrues to the demand to wear a collared shirt to work or put a napkin on one’s lap while eating: customs like these are contingent, local practices a large part of whose purpose is to mark off the one who observes them as a member of polite society. Meanwhile, even those aspects of good manners whose justification seems more fundamental, such as keeping disparaging thoughts to oneself and refraining from interrupting one’s conversational partners, are all such as to be dispensable in certain situations. What force do they have, then, except as the impositions of an oppressive, socially stratified culture? Read more »

by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

1.

It was at the height of Obama’s massive acceleration of George W’s drone program, when city planner Asher J Kohn began imagining his drone-proof “Shura City.” He did this, he said, “Out of the realization that the law had no response to drone warfare.” And so he came up with his concept of Shura City, ostensibly in the hope that by rendering military drones less efficient for “apprehending” targets in the Middle East, the US would be forced to return to police actions under international law.

The reaper drone that carried out the killing of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani on January 2 was part of a military program that had its origins in the pilotless hot-air balloons the Austrians used to bomb Venice in the late 19th century, as well as experimental remote control airplanes developed in the First World War. But, in terms of application and ethical issues, they are mainly seen as an extension of the aerial bombing campaigns of WWII.

Aerial bombing was a game changer in war: no longer would the world watch as two armies faced off on a battlefield–for the future was of indiscriminate bombing of cities from above. The line between combatant and non-combatants was effectively blurred forever with aerial bombing –and, not surprisingly, civilian deaths skyrocketed.

When viewed from this history, targeted drone strikes seem a natural and more efficient way to kill an enemy. Read more »

by Michael Liss

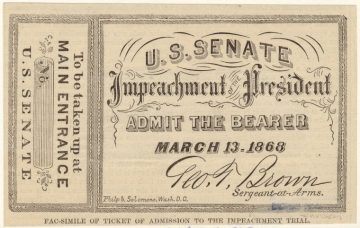

I have an awful confession to make. I haven’t made up my mind about whether President Trump should be convicted and removed from office.

I have an awful confession to make. I haven’t made up my mind about whether President Trump should be convicted and removed from office.

I know that sounds deranged. I am “troubled” by what Trump apparently did. “Disturbed” by the scorched-earth defense strategy put together by the Trump team. “Deeply concerned” about the continuous violations of norms and the virtual certainty they will continue.

All of these things are true, and I’m not even a moderate Republican trying to show my independence to the folks back home before voting to acquit. I’m a Democrat, and every day of the Trump Regime is an excruciating day. Nothing would make me happier than a landslide repudiation of Trump by a thoroughly repulsed electorate. I want him out, and I believe that, applying a probable cause standard, the House voted appropriately to Impeach and send it to the Senate. Nonetheless, I’m not sure that, if I were a Senator, I would vote to convict.

I need evidence. Old fashioned, I admit, but I need it anyway. I need a credible process with witnesses being called and a case being presented in a formal way. I need a sense that the system actually works, as opposed to just being a two-party rumble where few seem to care about facts, and fewer about process.

Three simple questions: What did the President do? Did he have the authority to do it? And, if so, did he abuse that authority beyond the breaking point? Read more »

Dr. Steven Fruchtman is a hematologist with extensive industry experience in clinical research for myelodysplastic syndromes, hematologic malignancies and solid tumors. He is an author of more than 170 lectures, presentations, books, and chapters. Previously, Dr. Fruchtman served as the Director of the Myeloproliferative Disorder Program at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York City and established the Stem Cell Transplant Program there. Dr. Fruchtman currently serves as President, Chief Executive Officer and Director at Onconova Therapeutics, Inc. in Pennsylvania. He is also on the board of The Bone Marrow Foundation.

Azra Raza, author of The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last, oncologist and professor of medicine at Columbia University, and 3QD editor, decided to speak to more than 20 leading cancer investigators and ask each of them the same five questions listed below. She videotaped the interviews and over the next months we will be posting them here one at a time each Monday. Please keep in mind that Azra and the rest of us at 3QD neither endorse nor oppose any of the answers given by the researchers as part of this project. Their views are their own. One can browse all previous interviews here.

1. We were treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with 7+3 (7 days of the drug cytosine arabinoside and 3 days of daunomycin) in 1977. We are still doing the same in 2019. What is the best way forward to change it by 2028?

2. There are 3.5 million papers on cancer, 135,000 in 2017 alone. There is a staggering disconnect between great scientific insights and translation to improved therapy. What are we doing wrong?

3. The fact that children respond to the same treatment better than adults seems to suggest that the cancer biology is different and also that the host is different. Since most cancers increase with age, even having good therapy may not matter as the host is decrepit. Solution?

4. You have great knowledge and experience in the field. If you were given limitless resources to plan a cure for cancer, what will you do?

5. Offering patients with advanced stage non-curable cancer, palliative but toxic treatments is a service or disservice in the current therapeutic landscape?

by Rafaël Newman

When Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016, the poet Nora Gomringer expressed her satisfaction at the recognition thus afforded not only poetry, but in particular songwriting, which she identified as the very wellspring and guarantee of literature, citing in her appraisal such classical forebears as Sappho and Homer. In an article published in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Gomringer mocked the conventional Western view of letters, a canon founded on prose and the novel, and now challenged by the award to Bob Dylan: “Literature is serious, it is beautiful, it is a vehicle for the noble and the grand; poetry is for what is light, for the aesthetically beautiful, it can be hermetic or tender, it can tell its story in a ballad and, if especially well made, can invite composers to set it to music…”. But “such categories”, she went on to suggest, “are stumbling blocks and increasingly unsatisfying, since they have ceased to function”, in part because of the Academy’s willingness to step outside its comfort zone and award the prize to a popular “singer/songwriter”.

When Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016, the poet Nora Gomringer expressed her satisfaction at the recognition thus afforded not only poetry, but in particular songwriting, which she identified as the very wellspring and guarantee of literature, citing in her appraisal such classical forebears as Sappho and Homer. In an article published in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Gomringer mocked the conventional Western view of letters, a canon founded on prose and the novel, and now challenged by the award to Bob Dylan: “Literature is serious, it is beautiful, it is a vehicle for the noble and the grand; poetry is for what is light, for the aesthetically beautiful, it can be hermetic or tender, it can tell its story in a ballad and, if especially well made, can invite composers to set it to music…”. But “such categories”, she went on to suggest, “are stumbling blocks and increasingly unsatisfying, since they have ceased to function”, in part because of the Academy’s willingness to step outside its comfort zone and award the prize to a popular “singer/songwriter”.

The Nobel Committee, according to Gomringer, had thus acknowledged the primordially hybrid nature of literature, the inextricable relationship between sound and sense, meter and message that had from the outset refused to differentiate between music and verse, but rather had created the two simultaneously, a marriage of the Apollonian and the Dionysian that would be variously contested by purists in subsequent generations, but would never entirely disappear.

The Academy’s own rationale for its choice in 2016, however – that Dylan was distinguished “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition” – proposes a slightly different account of the intervening literary history, and a different agenda: an existing musical idiom, it suggested, had been revitalized by the advent of a novel lyrical form. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by R. Passov

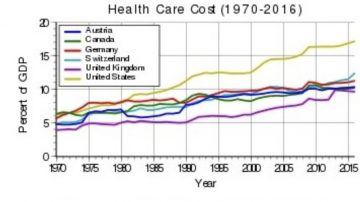

The economics of health insurance is of particular importance today. Health insurance has become a major issue of public policy. Some form of national health insurance is very likely to be enacted within the next few years. —Martin Feldstein 1

Fifty years ago, when healthcare expenditures were a mere 6% of US GDP, Martin Feldstein was afraid that the seemingly imminent adoption of some form of national health insurance would cause health care spending to grow unchecked.

Fifty years ago, when healthcare expenditures were a mere 6% of US GDP, Martin Feldstein was afraid that the seemingly imminent adoption of some form of national health insurance would cause health care spending to grow unchecked.

Turns out, like many economists, he was half right. While a truly national health scheme is still in the making, health care spending is now 18% of GDP, and growing.

Feldstein, known to his friends as Marty, was an interesting guy. For outstanding contributions to economics by an economist under 40, he was awarded the Bates Medal. He was President Reagan’s chief economic advisor, a long-time teacher at his alma matter, Harvard, and managed to retain the presidency and CEO titles at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) from 1977 until his passing in 2019. (He stepped aside from 1982 to 1984 to serve Reagan.)

The NBER describes itself as a private, non-profit research organization and then adds that it has been the source for most leaders of the Council of Economic Advisors. The Council is in fact a government entity, constituting the chief economic advisors to the Office of the President, while the National Bureau, which sounds like it is, is not.

Anyway, fifty years ago, Feldstein took his economics – the ‘markets solve everything’ kind – and reached the following conclusion: The problem with healthcare is Health Insurance. Eliminate insurance wrote Feldstein, and market forces would reign in the runaway price of health services. Read more »

Mark Moffett’s The Human Swarm: : How Our Societies Arise, Thrive, and Fall (Basic Books 2019) is nothing less than a comprehensive review and synthesis of the academic literature on social life in humans and a wide variety of animals, including, among many others, ants, whales, jays, wolves, and chimpanzees. While written for general readers, this book will repay academic specialists of various disciplines in the humanities and social sciences.

It is at heart a work of natural philosophy, an old term not in much use anymore. Moffett is interested in what constitutes society: how do we differentiate between insiders and outsiders? To do so he surveys the animal world and follows the distinction in the evolution of human societies from hunter-gatherer groups to the current day. Though Moffett has the skills and credentials of an academic specialist (he has a Harvard Ph. D.), he has written the kind of book specialists are discouraged from writing. That is all the more reason why those specialists must join interested “civilians” in reading The Human Swarm. For it is in books like this that many narrow specialized understandings are combined and synthesized into a more comprehensive understanding, in this case, understanding of the critically important issue of social identity. Read more »

by Bill Murray

This is Part Two in a series. Read Part One here.

Sooner or later even the best laid plans come full stop at the bureaucrat’s desk. At the entrance to Ngorongoro crater, Tanzania, we pull up short at a moldy branch of officialdom, no less out of place than some forlorn Chinese outpost on the Tibetan steppe. This requires twenty minutes of perfunctory paperwork, at night.

Stamp pads come out, ledgers are opened, numbers and details are transcribed and we will not proceed until the clerks accede. Which finally they do.

Difficult to get our bearings, arriving in the dark. There is only the tiny new moon that heralded Eid-al-Fitr, the end of Ramadan, and there are no lights out there because there is nothing built in the crater. We gaze into the gaping chasm for a while and then go off to eat.

I don’t know about this place. The restaurant is thatch-roofed, and the sound of gentle rain is comfy, but it’s scary how big and full the dining room is.

“We have more than 140 guests,” The server beams. I stare into my rice.

You want to be the only ones, the wilderness, the animals – Africa! – all to yourself. But this place is not like that.

Still, the shower is hot and a candle is provided. Alongside the candle is a matchbox with two, count ’em, matches. “Cleanext” brand tissues. Power goes out sometimes. Then it’s so dark you can’t even begin to see a thing outside. Not one thing. Anywhere. Clouds cover the little moon. Just 100% dark. Totality. Read more »

by Akim Reinhardt

Stuck is a weekly serial appearing at 3QD every Monday through early April. The Prologue is here. The table of contents with links to previous chapters is here.

![]() Back in 2014 I circled the country. It was a very long trip. From late August to early November I drove over 9,000 miles, all of it by myself. For many people, perhaps most, that kind of marathon driving day after day, particularly without someone to talk to, is only made bearable by listening to music. And given my own background, which has includes stints as a radio DJ, music critic, and rankly amateur musician, most everyone I know assumes I fall into that camp. Which is why they’re often shocked to find out that I don’t.

Back in 2014 I circled the country. It was a very long trip. From late August to early November I drove over 9,000 miles, all of it by myself. For many people, perhaps most, that kind of marathon driving day after day, particularly without someone to talk to, is only made bearable by listening to music. And given my own background, which has includes stints as a radio DJ, music critic, and rankly amateur musician, most everyone I know assumes I fall into that camp. Which is why they’re often shocked to find out that I don’t.

In fact, I do most of my long distance driving in silence. No mp3s, no CDs, no tapes, no radio, no singing outloud. Just the sounds of the road.

I love music as much as anyone I’ve ever known, but there is a time and a place for everything. And for me, the open road at 80 miles per hour is usually the time and place when I breath easily and clear my mind. I settle into the groove of the engine and the hum of the rubber rolling over the blacktop. I stare calmly at the world passing by. After a while, driving the contours of America becomes meditative. There’s no knowing what will pass in and out of my mind hour after hour. And when I finally pull over with a few hundred more miles on the odometer, I feel mentally refreshed and damn near at peace.

Often in my travels, there is no space for music roaring from the car speakers. Instead, I mostly crave the quiet, ambient sounds of the road and the magnificent machine that transports me over it.

When I tell people this, they often look at me in horror. Read more »

by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

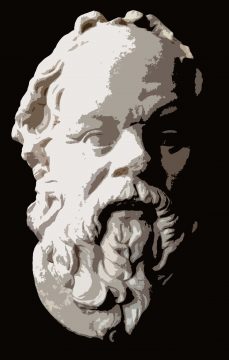

When people talk about Socrates, they typically refer to the leading character in Plato’s dialogues. This is because little is known about the historical Socrates beyond the fact that he wandered barefoot around Athens asking questions, an activity that got him executed for religious invention and corrupting the youth in 399 BCE. The relation between the historical figure and the Platonic character is debatable. In any case, Plato’s Socrates is most commonly read as a staunch anti-democrat. However, once one distinguishes between being opposed to democracy from theorizing the ways democratic society can fail, the relationship between Socrates and democracy grows more complicated.

The depiction of Socrates as an anti-democrat draws largely from the scathing critique he launches in Plato’s masterpiece, The Republic. There, Socrates famously characterizes democracy as the rule of the unwise, corrupt mob. Like children loose in a candy store, the democratic herd pursues pleasure only, rewarding sweet-talkers and flatterers with the power of political office, who in turn exploit politics for their own gratification. The result is injustice. Accordingly, Socrates says, democracy ultimately dissolves into tyranny — a population of citizens dominated by their basest desires, and an opportunistic ruler that manipulates them for personal gain.

Socrates’ critique of democracy is formidable. Notice, however, that Socrates is laying out a vulnerability inherent within democratic politics that no advocate of democracy can afford to ignore. In fact, the tradition of democratic theory is largely focused on identifying ways in which this vulnerability can be mitigated. And popular discussions today about disinformation, corruption, and incivility tend to concede much of Socrates’ case. The point is that giving voice to a standing weakness of democracy does not by itself make one an anti-democrat. One might argue that a crucial part of democratic advocacy is to engage in criticism of extant democratic practice.

Yet in The Republic, Socrates also lays out a vision of the perfect city, the kallipolis, and it is decidedly undemocratic. Kallipolis is an absolute kingship where philosophers rule over a strictly stratified society in which everything is exactingly regulated, from education, production, and conquest to art, diet, sex, and parenting. According to the standard line, that Socrates proposes the kallipolis as the paradigm of justice entails that he is an anti-democrat. Read more »

Two young men greeted a new crew member on a ship’s quarterdeck almost 60 years ago to the day and, in a matter of weeks, by simple challenge, introduced this then 18 year-old who’d never really read a book through, to the lives that can be found in them. —Thank you A. Gaeta and E. Budde for your life-altering tinkering.

… —A night walk to the base library

The bay to my right (my rite of sea and asphalt:

I hold to shoulder, I sail, I walk the line)

the bay moved as I moved, but retrograde

as if the way I moved had something to do

with how the black bay moved

(as if in animation) backward, how it tracked

how it perfectly matched my pace, but

in direction opposed (Albert would have

a formula or two to say about this

if he were here), behind, over shoulder

a steel grey ship at pier transfigured

in cloud of cool white light— a spray

from lamps on tall poles ashore, and aboard

from lamps on mast and yards

among pins of antennae

that gleamed above its raked stack—

an electric cloud, a photon aura edges

feathered into night enveloped it as it lay

upon the shimmering skin of bay,

from here she’s still as the thought

from which she came: upheld steel on water

arrayed in light, heavy as weight, sheer as a bubble,

the line of pier beyond etched clean

as if cut by horizon’s knife

… ahead, a library

… behind, a ship at night

the bay to my right (as I said) slid dark

as the confluence of all nights

the light of low barracks and high offices

of base ahead spread west and skip off bay

each of its trillion tribulations jittering at lightspeed

fractured by bay’s breeze-moiled black surface in splintered sight

ahead the books I aim to read,

books I’ve come to love since Anthony & Ed

in the generosity of their own fresh enlightenment

teamed to bring bright tools to this greenhorn’s

stymied brain to spring its self-locked latch

to let crisp air in fresh as this breeze —and how

that breeze blew across a bay from where to everywhere

troubling Narragansett from then to me here now!

Jim Culleny

12/16/19

by Anitra Pavlico

As I sit here marveling at the inexorability of deadlines, even in the midst of holiday cheer, I consider that I should, in the absence of time for research ventures, write about “what I know.” Isn’t that the default advice for people who don’t know what to write about and don’t want to come across as false? Well, I spend at least half of my time, and most of my psychic energy, on tasks stemming from being a mother. But do I “know” anything about it? For example, how do you get your child to become a good person, and by that I don’t mean compliant or obedient, but ethical? I spend a lot of time fretting about it, but I don’t know if I have any answers.

As I sit here marveling at the inexorability of deadlines, even in the midst of holiday cheer, I consider that I should, in the absence of time for research ventures, write about “what I know.” Isn’t that the default advice for people who don’t know what to write about and don’t want to come across as false? Well, I spend at least half of my time, and most of my psychic energy, on tasks stemming from being a mother. But do I “know” anything about it? For example, how do you get your child to become a good person, and by that I don’t mean compliant or obedient, but ethical? I spend a lot of time fretting about it, but I don’t know if I have any answers.

There are different schools of thought. One uses promises of gifts or other rewards. My husband’s friend has recommended Oreos as a relatively inexpensive behavior modification device. A variant of this philosophy cajoles children into thinking that whenever they act rightly, some outside entity, beyond the family unit, will reward them. Santa Claus is an outcropping of this parenting-out-of-desperation. One problem with this is that, as they grow older, young people soon realize that there is no one who necessarily rewards them when they act in a moral or ethical manner. Who’s to say whether children who became addicted to rewards following right actions might abandon the high road when the rewards stop coming?

Another school of thought relies on the threat of force or other recrimination. Sadly, these methods have waned, but haven’t completely gone out of style. Do this, or I will do that. Don’t do this, or I will take away that. Yet even children are aware that bad behavior is not always punished. After all, if you do something wrong while the strict teacher’s back is turned, there may be no repercussions at all. Instead of a sense of guilt, there is exhilaration at escaping a harrowing punishment. It is hard to see where the learning takes place. Read more »