by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

1.

It was at the height of Obama’s massive acceleration of George W’s drone program, when city planner Asher J Kohn began imagining his drone-proof “Shura City.” He did this, he said, “Out of the realization that the law had no response to drone warfare.” And so he came up with his concept of Shura City, ostensibly in the hope that by rendering military drones less efficient for “apprehending” targets in the Middle East, the US would be forced to return to police actions under international law.

The reaper drone that carried out the killing of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani on January 2 was part of a military program that had its origins in the pilotless hot-air balloons the Austrians used to bomb Venice in the late 19th century, as well as experimental remote control airplanes developed in the First World War. But, in terms of application and ethical issues, they are mainly seen as an extension of the aerial bombing campaigns of WWII.

Aerial bombing was a game changer in war: no longer would the world watch as two armies faced off on a battlefield–for the future was of indiscriminate bombing of cities from above. The line between combatant and non-combatants was effectively blurred forever with aerial bombing –and, not surprisingly, civilian deaths skyrocketed.

When viewed from this history, targeted drone strikes seem a natural and more efficient way to kill an enemy. Read more »

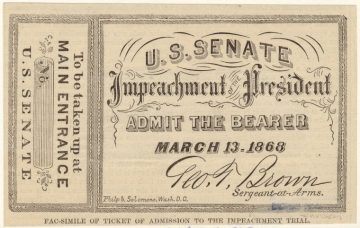

I have an awful confession to make. I haven’t made up my mind about whether President Trump should be convicted and removed from office.

I have an awful confession to make. I haven’t made up my mind about whether President Trump should be convicted and removed from office. When Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016, the poet Nora Gomringer expressed her satisfaction at the recognition thus afforded not only poetry, but in particular songwriting, which she identified as the very wellspring and guarantee of literature, citing in her appraisal such classical forebears as Sappho and Homer. In an article published in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Gomringer mocked the conventional Western view of letters, a canon founded on prose and the novel, and now challenged by the award to Bob Dylan: “Literature is serious, it is beautiful, it is a vehicle for the noble and the grand; poetry is for what is light, for the aesthetically beautiful, it can be hermetic or tender, it can tell its story in a ballad and, if especially well made, can invite composers to set it to music…”. But “such categories”, she went on to suggest, “are stumbling blocks and increasingly unsatisfying, since they have ceased to function”, in part because of the Academy’s willingness to step outside its comfort zone and award the prize to a popular “singer/songwriter”.

When Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016, the poet Nora Gomringer expressed her satisfaction at the recognition thus afforded not only poetry, but in particular songwriting, which she identified as the very wellspring and guarantee of literature, citing in her appraisal such classical forebears as Sappho and Homer. In an article published in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Gomringer mocked the conventional Western view of letters, a canon founded on prose and the novel, and now challenged by the award to Bob Dylan: “Literature is serious, it is beautiful, it is a vehicle for the noble and the grand; poetry is for what is light, for the aesthetically beautiful, it can be hermetic or tender, it can tell its story in a ballad and, if especially well made, can invite composers to set it to music…”. But “such categories”, she went on to suggest, “are stumbling blocks and increasingly unsatisfying, since they have ceased to function”, in part because of the Academy’s willingness to step outside its comfort zone and award the prize to a popular “singer/songwriter”.

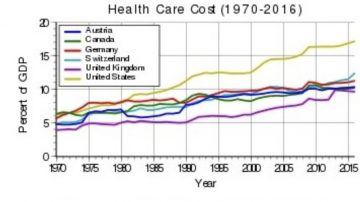

Fifty years ago, when healthcare expenditures were a mere 6% of US GDP, Martin Feldstein was afraid that the seemingly imminent adoption of some form of national health insurance would cause health care spending to grow unchecked.

Fifty years ago, when healthcare expenditures were a mere 6% of US GDP, Martin Feldstein was afraid that the seemingly imminent adoption of some form of national health insurance would cause health care spending to grow unchecked.

As I sit here marveling at the inexorability of deadlines, even in the midst of holiday cheer, I consider that I should, in the absence of time for research ventures, write about “what I know.” Isn’t that the default advice for people who don’t know what to write about and don’t want to come across as false? Well, I spend at least half of my time, and most of my psychic energy, on tasks stemming from being a mother. But do I “know” anything about it? For example, how do you get your child to become a good person, and by that I don’t mean compliant or obedient, but ethical? I spend a lot of time fretting about it, but I don’t know if I have any answers.

As I sit here marveling at the inexorability of deadlines, even in the midst of holiday cheer, I consider that I should, in the absence of time for research ventures, write about “what I know.” Isn’t that the default advice for people who don’t know what to write about and don’t want to come across as false? Well, I spend at least half of my time, and most of my psychic energy, on tasks stemming from being a mother. But do I “know” anything about it? For example, how do you get your child to become a good person, and by that I don’t mean compliant or obedient, but ethical? I spend a lot of time fretting about it, but I don’t know if I have any answers.

In 1885 Mary Terhune, a mother and published childcare adviser, ended her instructions on how to give baby a bath with this observation:

In 1885 Mary Terhune, a mother and published childcare adviser, ended her instructions on how to give baby a bath with this observation:

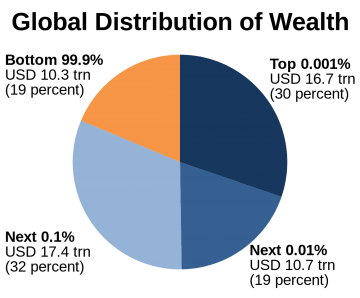

A 2011 survey by Michael Norton and Dan Ariely, of Harvard’s Business School, found that the average American thinks the richest 25% of Americans own 59% of the wealth, while the bottom fifth owns 9%. In fact, the richest 20% own 84% of the wealth, and the bottom 40% controls only 0.3%. An avalanche of studies has since confirmed these basic facts: Americans radically underestimate the amount of wealth inequality that exists – and the level of inequality they think is fair is lower than actual inequality in America probably has ever been. As journalist Chrystia Freeland put it, “Americans actually live in Russia, although they think they live in Sweden. And they would like to live on a kibbutz.”

A 2011 survey by Michael Norton and Dan Ariely, of Harvard’s Business School, found that the average American thinks the richest 25% of Americans own 59% of the wealth, while the bottom fifth owns 9%. In fact, the richest 20% own 84% of the wealth, and the bottom 40% controls only 0.3%. An avalanche of studies has since confirmed these basic facts: Americans radically underestimate the amount of wealth inequality that exists – and the level of inequality they think is fair is lower than actual inequality in America probably has ever been. As journalist Chrystia Freeland put it, “Americans actually live in Russia, although they think they live in Sweden. And they would like to live on a kibbutz.”