by Timothy Don

One of life’s great and illicit pleasures is spying on others. Put it on the list with smoking, gossiping, flirting with a stranger, ordering a cocktail at noon, calling in sick to lie abed for the day—all those small and tasty morsels we surreptitiously nibble when no one is looking that satisfy hidden and obscure appetites. Who does not remember creeping around as a child, poking into the corners of mother’s closet, uncovering brother’s stash of candy, cracking sister’s diary, the thrill of anticipation while easing open father’s desk drawer, the jolt of discovering a secret that someone we know has secreted away? Almost from the moment we realize how strange and foreign others are, especially those to whom we live in closest proximity, we peek and we prod and we dig. We spy on them. We know we shouldn’t, it’s wrong to sneak around, to rifle through papers, to examine dirty laundry, but…let’s take a peek. A small peek. Just a quick peek. It is an undeniable and delicious indulgence to do so.

The pleasure of spying is an erotic one, and not because it is prohibited or because the secrets one learns are sexual in nature. Recall that pornographic sex becomes boring the moment it has penetrated the last crevice, fleshed out the last secret, and left nothing to the imagination. There is no writer that will put you to sleep faster than the Marquis de Sade. Trust me. Spying, like knowledge, is erotic, precisely because it is always unfulfilled. One never actually gains the knowledge that would satisfy the appetite that seeks it. The pleasure lies in the expectation of discovery, not the thing discovered. How quickly one finds that, having reached over the wall and plucked a secret from someone else’s garden, the secret begins to wither and dry, to lose its luster and allure.

Spying, intelligence gathering, learning, gaining knowledge—these are not only synonymous acts. The charge they deliver is the same, and it is erotic. This is why the popular imagination so willingly and uncritically associates Commander James Bond, secret agent, with beautiful and accommodating women, even though we know that most spies are probably flabby, paper-shuffling, number-crunching geeks. Bond is a spy, so he knows things, and his job is to learn more things, and that’s what’s sexy about him. The job itself is sexy because the job is never finished; there is always another secret to be discovered, a mission to be undertaken. It’s not about the running and the jumping and the fighting, the fast cars, the good suits and the fancy gadgets. It’s not the tools that get the girls. It’s the trade.

The artist takes part in this trade too.

Think of da Vinci and his nocturnal dissections, his dark investigations into anatomy: da Vinci was a spy on behalf of humanism. Too much has been written about Velazquez’s Las Meninas, but it undeniably delivers a charge from the secret glance that artist and viewer exchange. Is there any painting in western history that casts the artist more concretely as a spy than Las Meninas? And then of course there is Courbet and L’Origine du Monde. What is most scandalous about the work is not its subject matter—a naked torso, a hirsute pudendum—but that it is presented as evidence of the artist’s experience. The outrageousness of the work lies in that it makes public an intimate secret. The shock is delivered in the claim that Courbet makes and the proof his painting delivers: “I have seen this body. You have not. I have known this body, personally. You have not. Here is the proof.” Whether or not they knew it, artists were always spies, and the best ones functioned as agents for the Republic of Aesthetics. That’s why they have such fun and such sex appeal. Artists dig and they hunt and they know things, about anatomy and power and pulchritude. They spy.

There is a rupture in the iconography of spying that occurs with the advent of photography in the mid-19th century. Apes in frockcoats, early photographers must have marveled and wondered at the tool they held in their hands. They were 19th century men operating 20th century technology, and it transformed and completed them. Almost as soon as they started using it and as soon as they began to understand the power of photography (literally, “light-writing”), something changed. The camera provided an immediacy and a transparency that painting did not. It did not eulogize or apotheosize. Its claim was objective. It captured people and moments. It did not create heroes, it revealed them. In an instant, quick as lightning, fast as a shutter’s flicker, the roles of the artist and the spy were united and fully realized in the person of the photographer.

We can see that unity most clearly today in the work of someone like Trevor Paglen. The subject of his work, broadly speaking, is mass surveillance and data collection, and his methods are those of the spy. He creeps up to within two miles or so of NSA sites, usually in the dark, digs in, hunkers down, pulls out a telescope and a camera with a massive lens, and captures the capturers.

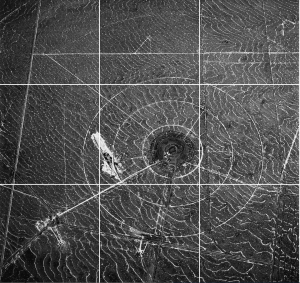

David Maisel climbs into a plane, flies through the air, opens a door, and hangs out from it to shoot American military zones, secret sites that reflect who and what we are and have become, collectively, as a society.

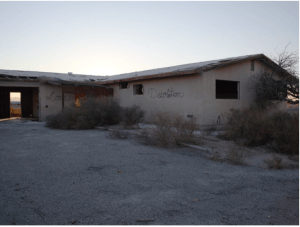

Last I checked, Richard Misrach was driving around the deserts of the American southwest, stealing up to abandoned, blown-out structures quite literally in the middle of nowhere and photographing graffiti left on their walls, gathering material from the pool of despond, a “twitter feed from underground,” as he describes it, that is evidence of a country overtaken in even its most liminal spaces by despair, hatred, grief, and hopelessness.

Each of these artists is doing work that is very different from the other, but all of it is ethereal and chilling, intelligent and important. And each of them behaves like a spy, creeping, flying, digging, and investigating. Finally, they are all spying on the spies. Using the tools of the master to dismantle his house, they complete and expand the circle of spying. But for each of them—and this should go without saying—the art comes first. Their work isn’t agitprop. It is sublime.

Were I to trace the urgency that animates their work and the geneology of the artist-as-spy back to its roots, I would be led through the cold war (a war of spies, if ever there were one) and Jasper Johns’ Target With Four Faces, 1956. I would stop along the way as well and pause over Edward Hopper’s paintings (Night Windows, 1928, in particular, which was the inspiration for Hitchcock’s Rear Window) and the voyeuristic opportunities of modern American cities. Finally, and perhaps arbitrarily, I would come to rest on the photograph below.

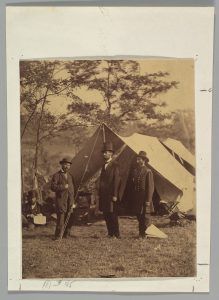

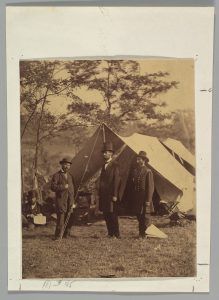

This is where it all begins, to my eye. This is the moment at which the artist, through the technological power of the camera, begins to wrest the activity of the spy out of the secret agent’s hands and reappropriate it as an aesthetic act. At first glance, this is merely a portrait, a record of a meeting among three men: Pinkerton, Lincoln, and McClerland. One can imagine the photographer asking them to stand up, compose themselves, and remain still. One can almost hearing him shouting, “Don’t move!”

But look at the poses his subjects have struck. Lincoln is stock still, embodying a rectitude that is overwhelmingly heavy. He must be exhausted by the metaphysical and psychic weight he is carrying. He is ever so slightly out of focus, as though swaying with tiredness, his knees begging to buckle, his arm hanging lifelessly at his side, a dead limb on this tree of a man who wants nothing more than to collapse. The pole that holds up the tent behind him provides spine, lends a straightness to Lincoln’s sag. General McClerland stands behind and to Lincoln’s left, faithfully mirroring his president’s pose, lending him support, bucking him up, caught between his duties to his leader and the exigencies of the present, expressed in the tension between his simultaneous mirroring of Lincoln’s attempt at straight-backedness and Pinkerton’s nonchalantly tucked hand. Both of them are looking out of the frame, into a past that is irredeemably lost. They look like 19th century versions of a Greek Kouros: stiff, posed, lifeless. Practically grave monuments.

And then there is Pinkerton. One look at him, and you know what is coming: the age of spies. Pinkerton is in control here. He’s got it figured out. The tent’s guy wire separates him from Lincoln and McClerland with the finality of a planar surface, which also functions as a fulcrum between the past and the future. Where Lincoln is stiff and uptight, Pinkerton is lithe and relaxed. Where Lincoln is kouros, Pinkerton is contrapposto. Where Lincoln is looking off camera, into the past, his gaze and posture rearticulated by General McClerland, Pinkerton looks directly into the camera, into the future, his gaze and posture rearticulated by the unnamed man sitting behind him. This photograph is not a record of the past or the portrait of a president. It is an omen of the future, and its subject is the spy, Pinkerton. With this photograph, Alexander Gardner delivers into our hands secret information about the future that is coming. A future that will belong to spies and goons, a future of secret services and black sites, a future of surveillance and data mining. A future whose most powerful pushback will come from artists.

I can only wonder what Alexander Gardner must have thought as he was taking this photograph, and what he felt when he saw it developed. But when I look at it, 156 years and 4 days later, I am struck by the future it presages in the person of Allan Pinkerton, chief of the Secret Service of the United States, and the role that the artist might play as a spy who spies on the spies.