by Emily Ogden

The author learns to like it loud.

A friend of mine has an expression he uses when he isn’t wild about a book, or a show, or an artist. For people who like this sort of thing, he’ll say, this is the sort of thing they like. He’s giving his irony-tinged blessing: carry on, fellow pilgrims, with your rich and strange enthusiasms.

My friend is saying something, too, about being imprisoned by our tastes—or by our conscious ideas about our tastes, anyway. There I am, liking the sort of thing I like. How tiresome. Isn’t there some way out of this airless room? Trapped with our own preferences, we find we don’t quite like those things after all—we don’t like only them, we don’t like them unfailingly. Taste not a duty we can obey, nor will it obey us. It wells up from somewhere. It comes in through the side door. It is, at its best, a surprise.

I don’t like loud music. That at any rate has been the official word for some years. There was reason for doubt. In high school I listened to Nine Inch Nails in my pink-and-cream-colored bedroom, tracking the killer bees of The Downward Spiral as they veered from the right to the left headphone. Later, Venetian Snares drove me out of myself when that was what I needed. (If you don’t know the music of Venetian Snares, it is tinny, relentless, almost intolerable, highly recommended.) Nothing has ever been better than hearing Amon Tobin’s waves of musical and found noise at Le Poisson Rouge in New York, more or less alone. My tolerant friend came along but gently left me to myself after a while, perhaps because being in that basement club felt something like participating in a sonic weapon test. Could the sheer percussive force of a sound wave alter the rhythm of your heart? It seemed as though it might. I was ready to pay the price, and so were a lot of other people I saw standing rapt, alone, looking up.

But such times have been rare, and the last one was a while ago. Silence is OK with me. My spouse turns up Ty Segall. Segall is a rock guitarist, maybe the greatest of his generation. He sounds like a later, rougher, more musically omnivorous Marc Bolan (of T. Rex). For people who like that sort of thing, it is the sort of thing they like. I turn it down. I hate trying to talk over a guitar. We have two-year-old twins, and I’ve been inclined to think that there is clamor enough. By long association, the word my sons use for “bowl” is “broken.” The other day, one of the twins came running to me with four eggs, still intact, cradled in his arms. Besides the refrigerator, they can open the vegetable garden, the gate that lets the dogs out into the street—and the stereo cabinet.

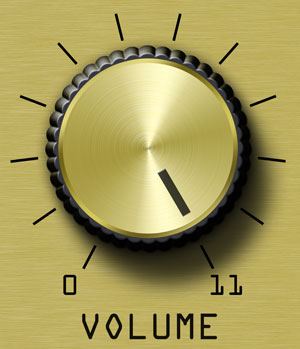

And when they open up the stereo, they play it loud. Very, very loud. As often as not they dial the volume up to eleven, then press power. After a chemical bleat that comes from either inside or outside my head, something musical and terrible turns out to be happening. If it’s Irish folk reels, I want to die. My sons wear their look of solemn, affectless absorption.

One time it was different for me. The blare was as bad as always. Then the flesh of my throat thickened. An aria was playing, a soprano voice. I teared up. It all happened in the space of ten seconds. Seeing one of my sons looking at me crying, I feared he would be frightened. How to explain what this was? What was this? Putting my hand to my heart, I said, opera, meaning, this is being moved to your soul. The simplest description I could think of was a total mystery to my sons, who had never before encountered the emotion, the gesture, or the word. Bop-ra, Thing One said, smacking himself on the chest happily. Bop-ra, said Thing Two, also smacking.

**

Did it have to be loud, did it have to be sudden, to seize me in that way? Possibly. Surprise matters to aesthetic experience. For one thing, it keeps us from deploying that arsenal of ideas we have about the sort of thing we like. These ideas may be accurate enough, most of the time. I’ll probably like this book, and not that one. I might buy a ticket to see a Four Tet concert with the idea that it will move me, and you might buy one to see the Dave Matthews Band for the same reason. Maybe this music once struck us dead, rooted us to the spot, gave us goosebumps, made us cry.

But we can’t bid it to move us again. Now, we’re standing at our concerts, checking to see if we are feeling anything yet, and our predictions themselves are killing our chance at a killer experience. Surprise jolts us out of these deadening frameworks. More than novelty, more than rarity, it tells us that this power isn’t ours, isn’t coming from us. I have seen and heard thousands of mourning doves in my life, and only one barn owl. But I would far rather look out my window and lock eyes, suddenly, with a mourning dove sitting on a wire, than go to a silo where a barn owl is known to live and find him duly peering down at me from a roof strut.

If surprise is so important, should we pick our books, our shows, our songs, at random? Should we ignore our tastes? No. We are not immortal. We are not going to hear all the songs in the world. Choices will have to be made. The trick is to wear the accumulated weight of those judgments lightly. The trick is to commute our own sentences from time to time. People I know who care about any form of art generally have their tastes, but court surprise. They submit themselves to the hazard of browsing a shelf or listening to a free-form radio DJ; they invite an assault on the senses; they take drugs. All these rituals circumvent our predictions, so that a light can flash up from our peripheral vision.

These flashes aren’t surprising simply because they are new. In fact, it may be that they can’t be altogether new if they are to seize us in the way I mean. My twins are arrested, twenty times a day, by a new experience: the movement of an earthworm, the passing of an illuminated tow truck. Their emotional range is fine; the rage of an Achilles pulsates in their little breasts. But beauty has never made their hearts turn piteous within them. What they don’t have yet is a lifetime of transporting experiences, half-remembered, imperfectly integrated. One day they will. And then there will come a moment when these experiences, in a condensed form, will flash up at them in a work of art. That will be a surprise in the sense I mean.

I had no time, before the opera came on, to frame the music deliberately. I didn’t recognize the song, and having looked up the radio playlist later, I still don’t; it was from Beatrice di Tenda, an opera I had never heard. But not all framing is a matter of conscious deliberation—or, for that matter, of curatorial knowledge. A life came back in those ten seconds. The disjointed experiences of liking loud music in spite of myself. The extremity of the first opera I saw, after a night of dancing when someone crossed an ugly line; after an early morning train ride with my best friend from college, hungover, chastened, cold; after a walk through a blazing red velvet lobby; after all those things came the opera itself: the black fabulous beauty of the Tales of Hoffman, suspended all around us in the dark, the squalor of human beings fully remembered in it but transformed.

When the opera came on, those things all returned, those things that amount to a life. Surprise is when the music gives all of that back to you. Surprise is when you don’t expect it, but you ask for it. And the music says, here.

**

The preparation for aesthetic experience has already started in my sons. Illuminated tow trucks have gained significance through encounters too numerous and minor to mention. Both boys seem to fixate, with the beginnings of pity, on pictures in their books of trucks getting stuck. They themselves hate to be stuck. I may have felt the same when I was small. The first work of art I can remember weeping over was my grandmother’s needlepoint Christmas stocking of a bear entangled in popcorn garlands. For the duration of one holiday season, I cried every time I saw that bear. He gathered something up, for me, besides his popcorn strands.

Opera means something to my sons, ever since that day. It may not last. But for now, they turn on the stereo and look up hopefully, smacking their chests: bopra? they ask. The one time the Sunday opera matinee happened to be on the radio again, they were overjoyed. They like to see marked emotion in adults; astonishingly sensitive to a feeling’s intensity level, they are terrible at gauging its affective tone. All transports are hilarious to them. They wanted to see their mother cry.

So did I, apparently. For me, too, something has been collected together of late, not in opera, but in loudness. I was wrong. Loud music is all right. Maybe I found it faintly masculo-hysterical before: men, eternally men, pumping their car stereos on spring days, manspreading. And I suppose those rattling bass beats do invade other people’s space sometimes. But when you play it loud, the car and the ribcage that tremble first of all are your own. You violate yourself. Get in my head, you say to the music. Break open my heart.

I found a CD of Ty Segall’s Sleeper in the back of the car the other day. I couldn’t have told you so a few weeks ago, but Sleeper is a nearly perfect album, with acoustic drives that give way to walls of electric fuzz in which—preposterously, triumphantly—a fiddle sometimes predominates. The atmosphere is harsh, a little ominous, pervaded with irony. And yet Segall goes all in on a song structure you know from every chart-topper you have ever heard: his tracks build from simple to complex, then at the end, they soar. Segall made the last song on the album sound like the last person you would ever expect, just because he could. Who is that person? Woody Guthrie. Believe me, it works. I can tell you all this now because when I put that CD in, I turned up the volume. Surprise me, Ty Segall, I said. And he did.