by Peter Wells

Well, I’ve looked at David Goodhart’s book (The Road to Somewhere – The New Tribes Shaping British Politics: 2017) and I’m obviously an Anywhere. [All quotes are from the Kindle edition]. “They tend to do well at school [Well, reasonably], then usually move from home to a residential university in their late teens [Yes] and on to a career in the professions [Teaching] that might take them to London or even abroad [Yes, indeed] for a year or two [or eighteen!]. Such people have portable ‘achieved’ identities, based on educational and career success which makes them generally comfortable and confident with new places and people [Generally!].”

Well, I’ve looked at David Goodhart’s book (The Road to Somewhere – The New Tribes Shaping British Politics: 2017) and I’m obviously an Anywhere. [All quotes are from the Kindle edition]. “They tend to do well at school [Well, reasonably], then usually move from home to a residential university in their late teens [Yes] and on to a career in the professions [Teaching] that might take them to London or even abroad [Yes, indeed] for a year or two [or eighteen!]. Such people have portable ‘achieved’ identities, based on educational and career success which makes them generally comfortable and confident with new places and people [Generally!].”

My father was lifted out of the conservative background of his family by several years of residential higher education, had a job which caused us to move every three or four years, and wired the house to broadcast BBC Radio 4 (or its predecessor, the Home Service) to every room. My infant toys included female as well as male dolls, and, what’s more, one of the females was a little black girl! (Don’t be condescending – we’re talking the late 40s!) The first black person I met was an African student on homestay with us, who shed light for me on the mysteries of Latin grammar (I returned the compliment by teaching Latin to Zimbabweans five years later!). (Sorry! I meant well!)

So I pass Goodhart’s worldview test: “This [sc. Anywhereism] is a worldview for more or less successful individuals [Check, though rather less than more!] who also care about society [Check]. It places a high value on autonomy, mobility and novelty [Check] and a much lower value on group identity, tradition and national social contracts (faith, flag and family) [Check]. Most Anywheres are comfortable with immigration, European integration and the spread of human rights legislation [Check]. They … see themselves as citizens of the world [Check 110%!].”

The privileges opened up to me by this certification were immense. Repeatedly during my career I was able to enter the ‘alien’ environments of foreign countries, in Africa, Asia and the Middle East – not as a tourist but as a resident, worker, colleague, neighbour and friend. Seeing how people of a different culture live, think, laugh, learn, befriend, commute, pay, greet, and grieve, enabled me to put my own attitudes and presuppositions into perspective. I realised that what had looked to me like a central and obvious norm was just the point of view that I happened to have been brought up with. My wife and I were offered a glimpse of at least five very distinctive ways to live, instead of the sole option that most people are granted. More than anything else, this is what makes working abroad a joy and delight. The elusive quality of a national culture defies stereotyping. Like the flavour of a loved one’s cooking, it is itself. Africans, Arabs, Japanese are not reducible to epithets: they are what they are. A spouse who has had the same experience will know what you mean when you say, “That’s just like Oman / Malawi / Japan, isn’t it.” Our friends have no idea what we are talking about! You can, of course, obtain a similar experience by visiting a different part of your own country, or even someone else’s house, but for the full culture shock you need to change countries! Read more »

According to Donald Trump, in a statement made to MSNBC’s “Morning Joe,” April 11, 2011, about the fake “birther controversy” of President Barack Obama—the opening salvo in Trump’s campaign of political disinformation—Obama’s “grandmother in Kenya said, ‘Oh, no, he was born in Kenya and I was there and I witnessed the birth.’ She’s on tape,” Trump went on. “I think that tape’s going to be produced fairly soon. Somebody is coming out with a book in two weeks, it will be very interesting.”

According to Donald Trump, in a statement made to MSNBC’s “Morning Joe,” April 11, 2011, about the fake “birther controversy” of President Barack Obama—the opening salvo in Trump’s campaign of political disinformation—Obama’s “grandmother in Kenya said, ‘Oh, no, he was born in Kenya and I was there and I witnessed the birth.’ She’s on tape,” Trump went on. “I think that tape’s going to be produced fairly soon. Somebody is coming out with a book in two weeks, it will be very interesting.”

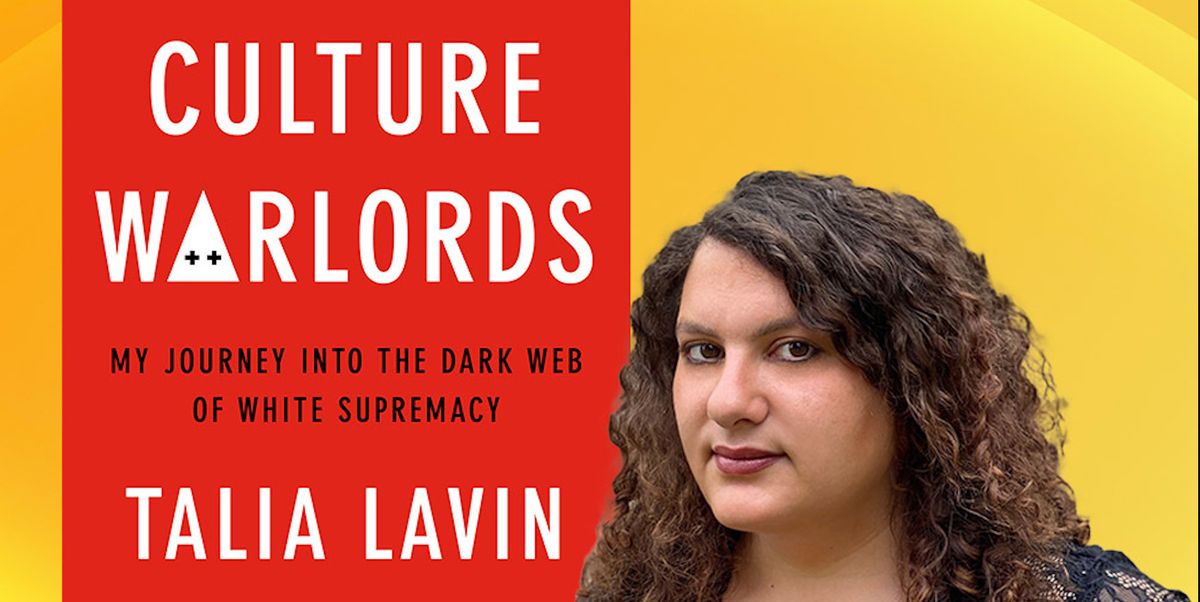

Recent protests in the US by Trump supporters since the election of Joe Biden, highlight just how political ideologies have the potential to tear seemingly ‘stable’ societies apart. A political divide however cannot always be seen as a clear-cut contradiction between the right and the left, as, for example, the way Trump supporters might assert; Biden, and Democrats more broadly, could hardly be seen to represent the left. Likewise, the right has it shades of commitment to conservatism. However, Trump’s 70 million supporters represent a congealing of far-right politics in America identifiable by the policies articulated by Trump that they endorse: anti- immigration, racism, a resurgent nationalism. While there is little doubt that such policies have been magical music to the ears of many right wingers, for others Trump and the Republican Party do not go far enough, and it is these extreme right-wing groups that are the subject of Talia Lavin’s book Culture Warlords: My Journey into the Dark Web of White Supremacists.

Recent protests in the US by Trump supporters since the election of Joe Biden, highlight just how political ideologies have the potential to tear seemingly ‘stable’ societies apart. A political divide however cannot always be seen as a clear-cut contradiction between the right and the left, as, for example, the way Trump supporters might assert; Biden, and Democrats more broadly, could hardly be seen to represent the left. Likewise, the right has it shades of commitment to conservatism. However, Trump’s 70 million supporters represent a congealing of far-right politics in America identifiable by the policies articulated by Trump that they endorse: anti- immigration, racism, a resurgent nationalism. While there is little doubt that such policies have been magical music to the ears of many right wingers, for others Trump and the Republican Party do not go far enough, and it is these extreme right-wing groups that are the subject of Talia Lavin’s book Culture Warlords: My Journey into the Dark Web of White Supremacists.

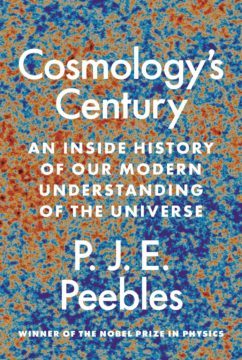

When I was seventeen years old, I took my first college science course, a summer class in astronomy for non-majors. The professor narrated his wild claims in an amused deadpan, calmly showing us how to reconstruct the life cycle of stars, and how to estimate the age of the universe. This course was at the University of Iowa, and I imagine that the professor was accustomed to intermittent resistance from students like me, whose rural, religious upbringing led them—led me—to challenge his claims. Yet I often found myself at a loss. The professor used a soft sell, and his claims seemed somewhere beyond the realm of mere politics or belief. Sure, I could spot a few gaps in his vision (he batted away my psychoanalytic interpretation of the Big Bang by saying he had never heard of Freud), but I envied him. I wished that my own positions were so easy to defend.

When I was seventeen years old, I took my first college science course, a summer class in astronomy for non-majors. The professor narrated his wild claims in an amused deadpan, calmly showing us how to reconstruct the life cycle of stars, and how to estimate the age of the universe. This course was at the University of Iowa, and I imagine that the professor was accustomed to intermittent resistance from students like me, whose rural, religious upbringing led them—led me—to challenge his claims. Yet I often found myself at a loss. The professor used a soft sell, and his claims seemed somewhere beyond the realm of mere politics or belief. Sure, I could spot a few gaps in his vision (he batted away my psychoanalytic interpretation of the Big Bang by saying he had never heard of Freud), but I envied him. I wished that my own positions were so easy to defend. Cosmology is a young science. Maybe the youngest. Some people say it started in the 1920’s when these little glowing clouds visible at certain points in the sky were found, by better and better telescopes, to be composed of billions and billions of stars, just like our own galaxy – the Milky Way – and it was then discovered that no matter what direction you looked they were all rushing away from us. More than one cosmologist has wondered if these galaxies know something that you and I don’t.

Cosmology is a young science. Maybe the youngest. Some people say it started in the 1920’s when these little glowing clouds visible at certain points in the sky were found, by better and better telescopes, to be composed of billions and billions of stars, just like our own galaxy – the Milky Way – and it was then discovered that no matter what direction you looked they were all rushing away from us. More than one cosmologist has wondered if these galaxies know something that you and I don’t. Many decades back when I was teaching at MIT, a senior colleague of mine, Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, a famous development economist, asked me at the beginning of our many long conversations what my politics was like. I said “Left of center, though many Americans may consider it too far left while several of my Marxist friends in India do not consider it left enough”. As someone from ‘old Europe’ he understood, and immediately put his hand on his heart and said “My heart too is located slightly left of center”. A 2015 study by psychologist Jose Duarte and his co-authors found that 58 to 66 per cent of social scientists in the US are ‘liberal’ (an American word, which unlike in Europe or India, may often mean ‘left of center’), and only 5 to 8 per cent are conservative. If anything, social scientists in the rest of the world are on average probably somewhat to the left of their American counterparts. If that is the case, for the world in general social democracy is likely to be an important, though not always decisive, ingredient of their ideology. In European politics and intellectual circles there was a time when social democrats were considered the main enemy of the communists, at least in their rivalry to get the attention of working classes, but now with the fading away of old-style communists, social democrats have a larger tent, which includes some socialists of yesteryear as well as liberals, besieged as they both now are by right-wing populists.

Many decades back when I was teaching at MIT, a senior colleague of mine, Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, a famous development economist, asked me at the beginning of our many long conversations what my politics was like. I said “Left of center, though many Americans may consider it too far left while several of my Marxist friends in India do not consider it left enough”. As someone from ‘old Europe’ he understood, and immediately put his hand on his heart and said “My heart too is located slightly left of center”. A 2015 study by psychologist Jose Duarte and his co-authors found that 58 to 66 per cent of social scientists in the US are ‘liberal’ (an American word, which unlike in Europe or India, may often mean ‘left of center’), and only 5 to 8 per cent are conservative. If anything, social scientists in the rest of the world are on average probably somewhat to the left of their American counterparts. If that is the case, for the world in general social democracy is likely to be an important, though not always decisive, ingredient of their ideology. In European politics and intellectual circles there was a time when social democrats were considered the main enemy of the communists, at least in their rivalry to get the attention of working classes, but now with the fading away of old-style communists, social democrats have a larger tent, which includes some socialists of yesteryear as well as liberals, besieged as they both now are by right-wing populists.

I’m disappointed in my columns so far. Not to say that they’ve been completely without value; I’ve managed to turn out some decent pieces and some kind readers have taken the time to tell me as much. But, taken together, my output exhibits a fault that I had sought to avoid from the outset. It has been far too occasional, too reactive, too of the moment in an extended, torturous moment of which I very much do not wish to be. There are exculpatory circumstances, of course. These are difficult times, and we are weak and vulnerable beings, and I am nothing if not an entrenched doom-scroller with a tendency for global anxiety. This is not an apology, because a core tenet of my approach to writing is a complete disregard for my audience. You’re all lovely people, I’m sure, but in order to write I have to provisionally discount your existence. This is, rather, a confession to the only person whose opinion matters to me as a writer. And that would be myself.

I’m disappointed in my columns so far. Not to say that they’ve been completely without value; I’ve managed to turn out some decent pieces and some kind readers have taken the time to tell me as much. But, taken together, my output exhibits a fault that I had sought to avoid from the outset. It has been far too occasional, too reactive, too of the moment in an extended, torturous moment of which I very much do not wish to be. There are exculpatory circumstances, of course. These are difficult times, and we are weak and vulnerable beings, and I am nothing if not an entrenched doom-scroller with a tendency for global anxiety. This is not an apology, because a core tenet of my approach to writing is a complete disregard for my audience. You’re all lovely people, I’m sure, but in order to write I have to provisionally discount your existence. This is, rather, a confession to the only person whose opinion matters to me as a writer. And that would be myself.

Ariana Reines and Terry Tempest Williams, writers one would never expect to be buddies, but who bonded at Harvard Divinity School, are having a public Zoom discussion in order to sell books. It’s a lovely, friendly discussion, but I’m shocked, shocked to hear that they send each other AUDIO letters. Audio letters? When they are so good at writing? When they have the chance to write to each other? Though, okay, why not? Henry James famously dictated his novels. Reines is amazingly articulate talking off the top of her head. Still, how is the pleasure the same? Williams does mention loving to actually write letters, so perhaps I shouldn’t judge.

Ariana Reines and Terry Tempest Williams, writers one would never expect to be buddies, but who bonded at Harvard Divinity School, are having a public Zoom discussion in order to sell books. It’s a lovely, friendly discussion, but I’m shocked, shocked to hear that they send each other AUDIO letters. Audio letters? When they are so good at writing? When they have the chance to write to each other? Though, okay, why not? Henry James famously dictated his novels. Reines is amazingly articulate talking off the top of her head. Still, how is the pleasure the same? Williams does mention loving to actually write letters, so perhaps I shouldn’t judge.

Well, I’ve looked at David Goodhart’s book (The Road to Somewhere – The New Tribes Shaping British Politics: 2017) and I’m obviously an Anywhere. [All quotes are from the Kindle edition]. “They tend to do well at school [Well, reasonably], then usually move from home to a residential university in their late teens [Yes] and on to a career in the professions [Teaching] that might take them to London or even abroad [Yes, indeed] for a year or two [or eighteen!]. Such people have portable ‘achieved’ identities, based on educational and career success which makes them generally comfortable and confident with new places and people [Generally!].”

Well, I’ve looked at David Goodhart’s book (The Road to Somewhere – The New Tribes Shaping British Politics: 2017) and I’m obviously an Anywhere. [All quotes are from the Kindle edition]. “They tend to do well at school [Well, reasonably], then usually move from home to a residential university in their late teens [Yes] and on to a career in the professions [Teaching] that might take them to London or even abroad [Yes, indeed] for a year or two [or eighteen!]. Such people have portable ‘achieved’ identities, based on educational and career success which makes them generally comfortable and confident with new places and people [Generally!].”

One of the strangest books to come out of Europe in the sixteenth century – and that is saying a lot – is John Dee’s

One of the strangest books to come out of Europe in the sixteenth century – and that is saying a lot – is John Dee’s