by Thomas O’Dwyer

The Nobel Prize season is almost upon us and writers who cover the events are poised as usual to see if the awards ride in on any juicy scandals. In particular, we’re watching you, Peace and Literature. This pandemic year’s winners will have no glitter to adorn their prizes, no lavish dinners, no rubbing shoulders with royalty. Of all the Nobel Prizes, Literature has been the most battered in the 120 years of their existence. The very first prize in 1901 was roundly criticised. It went to a now-forgotten French poet, Sully Prudhomme, instead of to the literary world’s favourite candidate, Leo Tolstoy. And so it has continued, with annual winners variously denounced as too Swedish (seven of them), too obscure, too European, too male (only 15 women out of 101 awards), too white, too unworthy, too shallow (sorry, Bob Dylan). The Nobel Committee itself collapsed in 2018 and awarded no prize after an internal sex and finance scandal. The list of controversies over ignored worthy authors is itself book-length — among them were Henrik Ibsen, Émile Zola, Mark Twain, James Joyce, Graham Green, Robert Graves.

One of the more offensive rejections by the Nobel Committee was in 1962 when Lawrence Durrell was dismissed in favour of John Steinbeck. This was “one of the Academy’s biggest mistakes” wrote one Swedish newspaper. On the day of the award, a critic asked Steinbeck if he deserved it. He replied, “Frankly, no.” Swedish journalist Kaj Schueler in 2013 revealed that Durrell was not chosen because “they did not think that The Alexandria Quartet was enough, so they decided to keep him under observation for the future”. Read more »

The stories in Seiobo There Below, if they can be called stories, begin with a bird, a snow-white heron that stands motionless in the shallow waters of the Kamo River in Kyoto with the world whirling noisily around it. Like the center of a vortex, the eye in a storm of unceasing, clamorous activity, it holds its curved neck still, impervious to the cars and buses and bicycles rushing past on the surrounding banks, an embodiment of grace and fortitude of concentration as it spies the water below and waits for its prey. We’ve only just begun reading this collection, and already László Krasznahorkai’s haunting prose has submerged us in the great panta rhei of life—Heraclitus’s aphorism that everything flows in a state of continuous change.

The stories in Seiobo There Below, if they can be called stories, begin with a bird, a snow-white heron that stands motionless in the shallow waters of the Kamo River in Kyoto with the world whirling noisily around it. Like the center of a vortex, the eye in a storm of unceasing, clamorous activity, it holds its curved neck still, impervious to the cars and buses and bicycles rushing past on the surrounding banks, an embodiment of grace and fortitude of concentration as it spies the water below and waits for its prey. We’ve only just begun reading this collection, and already László Krasznahorkai’s haunting prose has submerged us in the great panta rhei of life—Heraclitus’s aphorism that everything flows in a state of continuous change.

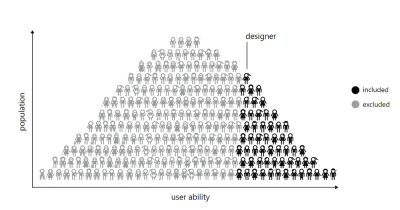

by Callum Watts

by Callum Watts

“Battle of Algiers”, a classic 1966 film directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, seized my imagination and of my classmates as well when it was shown three years later at the Palladium in Srinagar. A teenager wearing bell-bottoms, dancing the twist, I was a Senior at Sri Pratap College, named after Maharajah Pratap Singh, a Hindu Dogra ruler of Muslim majority Kashmir.

“Battle of Algiers”, a classic 1966 film directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, seized my imagination and of my classmates as well when it was shown three years later at the Palladium in Srinagar. A teenager wearing bell-bottoms, dancing the twist, I was a Senior at Sri Pratap College, named after Maharajah Pratap Singh, a Hindu Dogra ruler of Muslim majority Kashmir. I remember as a child watching the made-for-tv movie

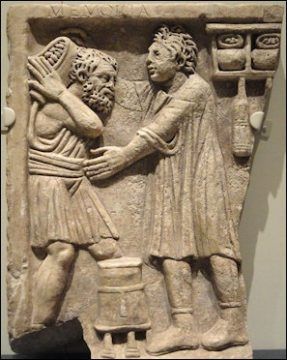

I remember as a child watching the made-for-tv movie  Whether or not a certain line of work is shameful or honorable is culturally relative, varying greatly between places and over time. Farmers, soldiers, actors, dentists, prostitutes, pirates and priests have all been respected or despised in some society or other. There are numerous reasons why certain kinds of work have been looked down on. Subjecting oneself to the will of another; doing tasks that are considered inappropriate given one’s sex, race, age, or class; doing work that is unpopular (tax collector); or deemed immoral (prostitution), or viewed as worthless (what David Graeber labelled “bullshit jobs”), or which are just very poorly paid–all these could be reasons why a kind of work is despised, even by those who do it. One of the oldest prejudices though, at least among the upper classes in many societies, is against manual labour.

Whether or not a certain line of work is shameful or honorable is culturally relative, varying greatly between places and over time. Farmers, soldiers, actors, dentists, prostitutes, pirates and priests have all been respected or despised in some society or other. There are numerous reasons why certain kinds of work have been looked down on. Subjecting oneself to the will of another; doing tasks that are considered inappropriate given one’s sex, race, age, or class; doing work that is unpopular (tax collector); or deemed immoral (prostitution), or viewed as worthless (what David Graeber labelled “bullshit jobs”), or which are just very poorly paid–all these could be reasons why a kind of work is despised, even by those who do it. One of the oldest prejudices though, at least among the upper classes in many societies, is against manual labour.

A life in which the pleasures of food and drink are not important is missing a crucial dimension of a good life. Food and drink are a constant presence in our lives. They can be a constant source of pleasure if we nurture our connection to them and don’t take them for granted.

A life in which the pleasures of food and drink are not important is missing a crucial dimension of a good life. Food and drink are a constant presence in our lives. They can be a constant source of pleasure if we nurture our connection to them and don’t take them for granted. At the beginning of our story—paraphrased from an origin story remembered by a

At the beginning of our story—paraphrased from an origin story remembered by a  There is a minor American myth about shame and regret. It goes like this.

There is a minor American myth about shame and regret. It goes like this.