by Callum Watts

by Callum Watts

Do identity politics and intersectionality clash with the idea of universal principles? There seems to be a rift emerging in left wing politics around precisely this point. On the one hand various organised identity groups are making it increasingly difficult to ignore the real effects of institutionalised prejudice on their lives. It seems like it’s only through the elevation of particular identities that these interests will be protected, and certain progressive goals reached. These movements reproach, often correctly in my view, the champions of universal rights and freedom as being coded as white, cis, able bodied and male. On the other hand there is a real concern that the elevation of particular identities prevents solidarity between different groups who have otherwise shared interests. This seems to be happening top down as politicians seek to exacerbate these identity markers to consolidate their supporters, and also bottom up as individuals see solidarity as being limited to others who belong to their own perceived identity groups.

It’s worth noting that these two views do not logically contradict each other. It is possible that identity based organising is key to raising the visibility of and guaranteeing rights for certain groups, whilst it also being true that doing this can inflame tensions between different groups and obscure shared interests. Whilst this is to be expected in the broader culture war between left and right, in progressive left circles this division is causing both soul searching, and increasingly, acrimony. There appears to be a reaction against identity politics coming from both the far left and the centre left. If we can ignore the concern trolling (of which there is undoubtedly a lot), the centre left seems to worry about losing the centre ground to a right wing movement that is co-opting the language of universal rights. From the far left we see the worry that identity politics undermines the possibility of a class politics which aims at redistribution.

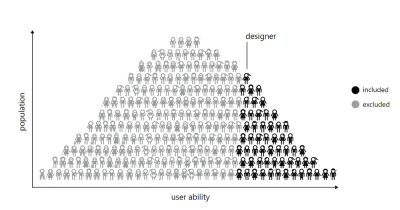

This conflict between universal political demands and the elevation of particular political identities at least creates the feeling of tension between erstwhile political allies, but it strikes me that much of it is misguided. The field of design offers an interesting analogy to think about this conflict. The practice of universal design shows us a methodology where focussing on particular needs can lead to universal solutions. Universal or inclusive design is the idea that objects should be designed so as to be universally accessible to all. This school of thought sees meeting the needs of traditionally excluded users not as a special requirement catering to a minority, but rather as a condition of good design itself. In fact in many cases, focusing on the needs of a particular subset of users can lead to products which are better for everyone. A classic case of this is the OXO good grips range. OXO’s founder, Sam Faber, was focussed on creating kitchen equipment which could be used by people with limited strength and dexterity, motivated by his wife who was suffering from arthritis and found it hard to use existing kitchenware comfortably. Faber was successful in creating a tool which she could easily use. But happily the quality of the resulting design was so good that today OXO’s equipment is just as likely to be found in the hands of a professional chef as in the hands of the users it was initially made for. Here we see how focussing on the most vulnerable user, we end up creating a product which has universal applicability.

There are countless more examples of this sort of success in design. It does not follow that everything can be designed in such a way, but what it does show us that there is no reason to think that the mere fact of focussing on some particular set of users necessarily excludes the interests of others. In fact we might use this kind of metaphor to imagine how focussing on a minority of citizens might itself be an important step to creating social goods to the benefit of everyone. The activist and educator Anna Julia Cooper famously said that “the Black Woman can say, when and where I enter … then and there the whole Negro race enters with me.” Meaning that as the most excluded member of a community, whatever guarantees her inclusion necessarily guarantees the inclusion of everybody else. And thought of this way identities that are at the margin become absolutely central, because by designing systems that are responsive to them, we might stand some chance of designing systems that are responsive to everyone.

In the policy space we can see how BLM’s focus on police reform can be seen as beneficial not just in some communities, but to all communities which suffer from heavy handed policing, and to any other individual who might have a difficult encounter with the police, in other words, to anyone. If we start by trying to understand the challenges and experiences of those who are systematically excluded or mistreated by institutions, it should be possible to design better politics for everyone. In fact policies and institutions designed to be able to support the most vulnerable, say the National Health Service in the UK, often become universally popular because they are able to benefit everybody. The NHS has a low barrier to entry, in that it will cater to someone with no income and no fixed address, and it is the fact that is free at the point of entry and readily accessible which makes it so popular, even by those who are fortunate enough to have the resources to go private.

There are at least 2 lessons here. First, focussing on the interests of those who are traditionally excluded need not come at the material expense of other groups that are slightly less excluded, or even at the expense of more privileged groups. The social and political programmes which benefit these groups can be of universal benefit. Secondly, good design outcomes require really understanding key users, this means engaging with their lived experience. By analogy, people concerned about identitarian political movements replacing universal ideals (of whatever flavour) need not worry too much, in fact doubling down on engaging with the lived experiences and narratives of particular individuals and groups might create the knowledge needed to build the best possible universal programmes. Including important users in the design process, so that design is not something that is done too them, is a powerful way of creating the best solutions, so similarly, a focus on the lived experience of certain groups, and supporting them to drive change, may well be the best way of furthering positive political outcomes for everyone.

I don’t want to claim that it is literally impossible that there be conflict between identitarian/intersectional politics and universal programmes focused on rights or class. And as a point of political strategy for the upcoming US election, it’s worth being careful about how effective this kind of message is as a campaign rhetoric. However I do want to argue that there is no deep philosophical or practical impossibility to being focussed on the needs of certain individuals and identities, and being seriously committed to a universalist programme of some sort. Hopefully looking to other fields like design can give us the tools to imagine what that can look like in the political space.