by Thomas O’Dwyer

The Nobel Prize season is almost upon us and writers who cover the events are poised as usual to see if the awards ride in on any juicy scandals. In particular, we’re watching you, Peace and Literature. This pandemic year’s winners will have no glitter to adorn their prizes, no lavish dinners, no rubbing shoulders with royalty. Of all the Nobel Prizes, Literature has been the most battered in the 120 years of their existence. The very first prize in 1901 was roundly criticised. It went to a now-forgotten French poet, Sully Prudhomme, instead of to the literary world’s favourite candidate, Leo Tolstoy. And so it has continued, with annual winners variously denounced as too Swedish (seven of them), too obscure, too European, too male (only 15 women out of 101 awards), too white, too unworthy, too shallow (sorry, Bob Dylan). The Nobel Committee itself collapsed in 2018 and awarded no prize after an internal sex and finance scandal. The list of controversies over ignored worthy authors is itself book-length — among them were Henrik Ibsen, Émile Zola, Mark Twain, James Joyce, Graham Green, Robert Graves.

One of the more offensive rejections by the Nobel Committee was in 1962 when Lawrence Durrell was dismissed in favour of John Steinbeck. This was “one of the Academy’s biggest mistakes” wrote one Swedish newspaper. On the day of the award, a critic asked Steinbeck if he deserved it. He replied, “Frankly, no.” Swedish journalist Kaj Schueler in 2013 revealed that Durrell was not chosen because “they did not think that The Alexandria Quartet was enough, so they decided to keep him under observation for the future”.

Durrell was also denied the previous year, 1961, according to the committee’s records, “because he gives a dubious aftertaste … because of his monomaniacal preoccupation with erotic complications”. Whatever that obscurity means, it was a flimsy dismissal of the magnificent quartet. Yugoslav writer Ivo Andrić won the 1961 Nobel, later sparking decades of ethnic controversy as the country disintegrated. In a literary coincidence, Durrell had published a popular young adult novel, White Eagles Over Serbia in the same year as Justine, the first volume of The Alexandria Quartet.

Unlike many of the rapidly forgotten “winners”, and despite the occasional sniffy critic wondering “who still reads it?” Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet has never been out of print since he published it in 1957. The centenary of his birth in 2012 raised a flurry of revived interest in Durrell. Indeed the whole Durrell family has been popping up regularly in reprints of Lawrence’s novels and poetry, in his brother Gerald’s popular tales of his “family and other animals,” and in several TV series about their life in Greece on Corfu island in the late 1930s. A BBC interviewer once asked Lawrence about the difference between his writing and brother Gerald’s. He replied: “I write literature. My brother writes books that people read.”

It was an astutely accurate observation. Readership is always limited for novels like The Alexandria Quartet, or his later less-successful Avignon Quintet, or for Anthony Powell’s 12-volume A Dance to the Music of Time, or Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. But all these masterworks have been in print since they were first published and so can claim as dedicated a following as any other popular niche genres.

What is captivating about the Quartet is Durrell’s ability to trap the essence of places, times and people in language that is layered and luscious, like life itself. In such classic literature, the prose does date, the people fade away into sepia prints, events that were once urgent become history’s trivia, the affairs that were passionate and sexy are at best, “what were we thinking?”, at worst, embarrassing. And yet reader after reader, critic upon critic, have told how they keep returning to the Quartet. As a person ages, the fading fictional memories of a Levantine city may burnish and brighten our own memories in our parallel universes. “I return link by link along the iron chains of memory to the city which we inhabited so briefly together,” muses the author on the first page of Justine, the lavishly written first volume that startled the literary world in 1957.

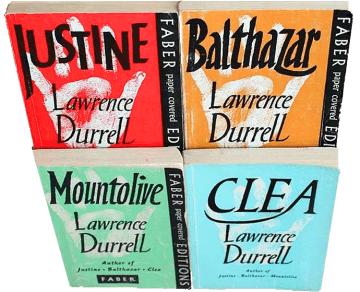

In the late 1970s, I first read Justine in a village house in south Cyprus where I had settled with a wife and young child. Durrell had completed the novel in a similar village in north Cyprus. “I have escaped to this island with a few books and the child — Melissa’s child. I do not know why I use the word ‘escape’. The villagers say jokingly that only a sick man would use such a place to rebuild. Well, then, I have come here to heal myself.” These opening sentences of Justine so startled me that I was hooked in empathy and galloped enthralled (and sometimes appalled) through it and the rest of the series — Balthazar, Mountolive and Clea.

Durrell was obsessed with the “spirit of place” in all his travels so it was no surprise that when asked about the leading characters in the Quartet, he invariably said the only real character was the city itself — Alexandria. He had a unique talent for transmitting that elusive spirit to his readers. Whispering between the crevices of progress, tourism and quotidian dross in countries with long histories but short memories, always we hear and feel in his writing the pneuma, the breath and soul, of voices in Alexandria, or the mythical deities riding the breezes in the Greek islands and Cyprus. Alexandria is now a sad and pedestrian metropolis but it was for centuries a pearl of the Mediterranean.

Alexander founded the city 331 BCE and its spirit remained closer to its northern neighbours than to the shifting sands of the Middle East. Its Pharos lighthouse was one of the seven wonders of the world, its great library of ancient texts was never surpassed. Cleopatra loved first Julius Caesar, then Antony, in her city palace. For Durrell, as for many others, the voice that echoed most enchantingly through the city was that of its greatest poet, the Greek Constantine Cavafy. The 1930s Alexandria of the Quartet is a city of cosmopolitan chaos — “five races, five languages, a dozen creeds,” writes Durrell. Greeks, Italians, Jews, Arabs, French, British, Turks and Armenians all hustle together and wander in and out of one another’s beds and brothels. He quotes Cavafy:

“You tell yourself: I’ll be gone

To some other land, some other sea,

To a city lovelier far than this

Could ever have been or hoped to be.”

The city’s ancient Greek character had faded. Greeks remained the largest European contingent but the travel writer Douglas Sladen had already written: “Alexandria is an Italian city; Italian is its staple language.” That seemed an exaggeration. Arabic was the people’s language, French the commercial and English the diplomatic. Durrell’s multitude of diplomats, teachers, traders, clerks, bureaucrats, journalists and bohemian cliques of writers and artists weave their way through the Quartet’s somewhat contrived literary space-time continuum. Space is filled with orientalist palaces, shabby embassies and consulates, artists’ garrets, workers’ hovels and hustlers’ seedy side-streets. Time shifts backwards, gets reinterpreted and jumps forward, or stands still. No one viewpoint is definitive – one narrator will review the tales told by another, declare them wrong and write a “corrected” version. If they are holding up a giant mirror to the city, it is a cracked one. The fractured images never quite form any coherent mosaic.

We can never know for sure if this Alexandria was ever real, but Durrell created an immortal spirit for such a place to exist. The first novel Justine is told by the writer Darley, a shadowy stand-in for the author Durrell. In Alexandria Durrell had met Eve Cohen, a Jewish Alexandrian who became his second wife and who inspired the character Justine. Darley also narrates the second book, Balthazar, but it completely alters our understanding of the events in Justine, by partially retelling them as edits and footnotes made by another writer (Balthazar).

The third book, Mountolive, retells the whole story from a third-person omniscient viewpoint. It reinterprets the perceptions of the characters by adding a bigger picture of the events unfolding in Alexandria and the wider world as global war approaches. (Mountolive is an ambassador). In the final volume, Clea, Darley returns as author after the war has started and he reveals that we never really knew the characters we have been living with because they are in constant motion, evolving in time and always changing. While much of the language in the Quartet is enchanting, the most common charge against it is of being over-written. To this Durrell pleaded guilty in a 1959 interview with The Paris Review:

“Interviewer: Your prose seems so highly worked. Does it just come out like that?

Durrell: It’s too juicy. Perhaps I need a few money terrors and things to make it a bit clearer — less lush. I always feel I am overwriting. I am conscious of the fact that it is one of my major difficulties.”

Today, Durrell’s prose may appear even more purple, his mahogany sentences over-carved. Yet, as a reader has aged and become used to it and to other distant writers too, it is not hard to cherish some of its lovely evocative passages:

“In the great quietness of these winter evenings, there is one clock: the sea. Its dim momentum in the mind is the fugue upon which this writing is made. Empty cadences of sea-water licking its own wounds, sulking along the mouths of the delta, boiling upon those deserted beaches — empty, forever empty under the gulls.”

Durrell returned to Alexandria in 1977 to help a BBC crew to find remnants of “his” city. They never did, nor will any modern visitor. “The city seemed to him listless and spiritless, its dreary harbour a mere cemetery, its famous cafés no longer twinkling with music and lights,” wrote Michael Haag, who was with the BBC crew, in his book Alexandria, City of Memory (2004). “Foreign posters and advertisements have vanished, everything is in Arabic; in our time film posters were billed in several languages with Arabic subtitles, so to speak.” (Haag’s book is itself an excellent tour of the city’s literary heritage during the first 50 years of the 20th century):

“Durrell’s favourite bookshop, Cité du Livre on the Rue Fuad, had gone, and others he found lamentable. All about him lay ‘Iskandariya,’ the uncomprehended Arabic of its inhabitants translating only into emptiness. … The Alexandria he saw in 1977, a quarter-century on from Egypt’s nationalist revolution, was a monochrome shadow of the city he had immortalized in the Quartet.”

Durrell’s spirit of places was always a flimsy thing, a barely perceived whiff of an exotic scent that fades as surely as a delightful dream. He was never any good at “going back”, not to the Greek islands, not to Cyprus, not to Egypt, not to Serbia, and certainly not to England, a soggy place so devoid of any spirit he called it “Pudding Island.” He came, he wrote, he conquered, and then there was always another Rubicon ahead. Durrell carried on a lifelong correspondence with his close friend Henry Miller in California. Miller’s robust American Tropic of Cancer had shocked a young Durrell out of his tweedy Eng-Lit mentality and in 1935 he wrote to Miller to tell him so. Here he is writing to Miller from northern Cyprus in October 1953:

“I am sorry to have neglected to write you so I’ve snatched these morning moments to do so. For the last two months, we’ve been building my little Turkish house in Kyrenia into something really beautiful. I haven’t even had a table to write on. In addition, I started an arduous job as a teacher which involves getting up at five every morning and working till two. … In addition, I have been working at a new manuscript “Justine” which is something really good I think – a novel about Alexandria – four-dimensional. I’m struggling to keep it taut and very short, like some strange animal suspended in a solution.”

And yet he has time to note the spirit of a Cypriot morning:

“I’m writing this at 4:50 AM. A faint lilac dawn breaking accompanied by bright moonlight appeared. Nightingales singing intoxicated by the first rains. Everything damp. In a little while I take the car and sneak down the dark road towards dawn coming up from Asia Minor like Paradise lost. I think you would like Cyprus in spite of it being so un-Greek — it is the lazy moist sensuality of the eastern Levant, of Egypt and Syria – the mindless sensuality which made the Sybarites. It is dimmed out, autumnal, sleep impregnated. It would not have suited me as a young man but now in my old age at 42 I think it is a good enough place to settle for a few years. Love Larry.”

But he was soon gone, again. World War II had driven him and the family out of Corfu, the end of the war ended his time in Alexandria, and in 1957 the war for Cypriot self-determination ejected him from Cyprus after he narrowly escaped being shot in his village tavern. In 1962, the Swedes dropped his name from the list of Nobel nominations. Durrell finally settled in a small village in Languedoc, France where he completed The Avignon Quintet and lived until his death in 1990. Avignon failed to capture the spirit, or the readership, of The Alexandria Quartet – and Durrell never again caught the eye of the Nobel Literature Committee. The spirit of literary accolades is also a flimsy whimsy.