by Jeroen Bouterse

The most charitable, forward-looking take on the science wars of the 90s is Stephen Jay Gould’s, in The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister’s Pox (2003), a delightful book about dichotomies between the sciences and humanities. His diagnosis is primarily that scientists have taken too literally or too seriously some fashionable nonsense, and overreacted; and if everybody can just calm down already, things will be alright and both sides could “break bread together” (108). Gould saw the science wars themselves as a marginal and slightly comical skirmish, almost a mere misunderstanding. “Some of my colleagues”, he said,

The most charitable, forward-looking take on the science wars of the 90s is Stephen Jay Gould’s, in The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister’s Pox (2003), a delightful book about dichotomies between the sciences and humanities. His diagnosis is primarily that scientists have taken too literally or too seriously some fashionable nonsense, and overreacted; and if everybody can just calm down already, things will be alright and both sides could “break bread together” (108). Gould saw the science wars themselves as a marginal and slightly comical skirmish, almost a mere misunderstanding. “Some of my colleagues”, he said,

“have become legitimately disturbed by a few truly silly and extreme statements from the ‘relativist’ camp, largely made by poseurs rather than genuine scholars, and have mistaken these infrequent sound bites of pure nonsense for the center of a serious and useful critique. Then, falsely believing that the entire field of ‘science studies’ has launched a crazed attack upon science and the concept of truth itself, they fight back by searching out the rare inane statements of a few irresponsible relativists […] and then presenting a polemic defense of science, ultimately helpful to no one”. (99)

Gould saw an example of such “windmill-bashing” in P.R. Gross and N. Levitt’s Higher Superstition: The Academic Left and Its Quarrels with Science (1994). He also saw it in Alan Sokal’s famous hoax: a brilliant and funny parody, which Gould thought did not really prove much beyond the laziness of the editors that he hoodwinked.

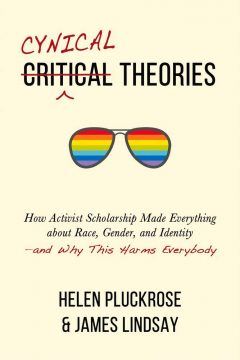

I thought a lot of these 1990s events when I bumped into their 21st-century descendants: first, the ‘Sokal squared’ hoax two years ago, which insisted on taking all the fun out of Sokal’s joke by multiplying it twentyfold. And now Cynical Theories, the equivalent of Higher Superstition, in which two of the same three authors aim their lance at what they perceive to be the heart of intellectual evil: postmodernism. Postmodernism denies reality and universal truth, and thinks that all categories and concepts are therefore functions of group power. These core postmodern motifs have developed (like a “fast-evolving virus”) into actionable left-wing ideas, in the form of a proliferation of cynical, pessimistic and anti-enlightened theories in fields such as gender studies and queer studies. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Light As a Feather. Boston, Sept 2020.

Sughra Raza. Light As a Feather. Boston, Sept 2020.

By the beginning of the 20th century, it had become clear to an influential minority of philosophers that something was badly amiss with modern philosophy. (There had been gripes of innumerable sorts since the beginning of modernity in the 17th century; but our subject today is the present.) “Modern” here means something like “Lockean and/or Cartesian,” where this means … well, it’s not immediately clear what exactly this means, nor what exactly is wrong with it, and therein lies the tale of a good deal of 20th-century philosophy. As with every broken thing, we have two choices: fix it, or throw it out and get a new one; and many philosophers have advertised their projects as doing one or the other. However, as we might expect, unclarity about the old results in corresponding unclarity about the supposedly better new. What’s the actual difference, philosophically speaking, between rehabilitation and replacement?

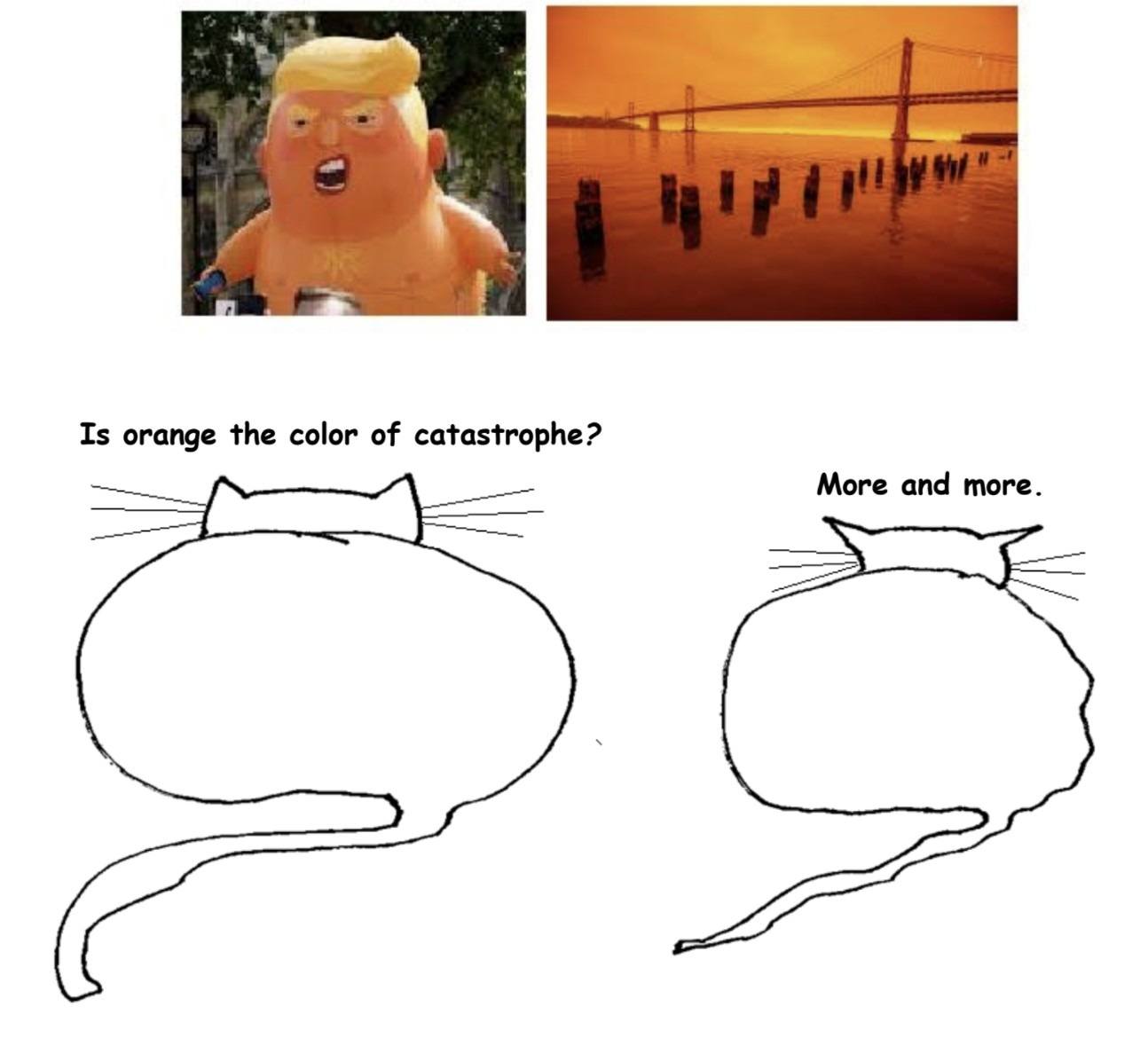

By the beginning of the 20th century, it had become clear to an influential minority of philosophers that something was badly amiss with modern philosophy. (There had been gripes of innumerable sorts since the beginning of modernity in the 17th century; but our subject today is the present.) “Modern” here means something like “Lockean and/or Cartesian,” where this means … well, it’s not immediately clear what exactly this means, nor what exactly is wrong with it, and therein lies the tale of a good deal of 20th-century philosophy. As with every broken thing, we have two choices: fix it, or throw it out and get a new one; and many philosophers have advertised their projects as doing one or the other. However, as we might expect, unclarity about the old results in corresponding unclarity about the supposedly better new. What’s the actual difference, philosophically speaking, between rehabilitation and replacement? Over the course of two days in early September, the Trump administration quietly formalized its commitment to the ideology of white supremacy within the context of schooling and public education. In two separate but parallel moves, both of which would have made Senator Joe McCarthy proud, Trump announced that the Department of Education (DOE) would investigate public schools to determine if they were using the Pulitzer-Prize winning curriculum, The

Over the course of two days in early September, the Trump administration quietly formalized its commitment to the ideology of white supremacy within the context of schooling and public education. In two separate but parallel moves, both of which would have made Senator Joe McCarthy proud, Trump announced that the Department of Education (DOE) would investigate public schools to determine if they were using the Pulitzer-Prize winning curriculum, The

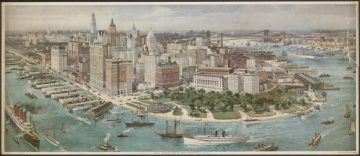

I’ve telecommuted from home for many years now. Before COVID-19, I would rarely turn my camera on when I was on video chats. And if I did, I’d make sure to put makeup on and look somewhat professional and put together from at least the waist up. But since lockdown started in March, I now turn my camera on for almost every video call and I don’t bother to put makeup on or to change my clothes from whatever ratty t-shirt I happen to be wearing. And I don’t care. I sit in my armchair au natural, secure in the knowledge that everyone I’m on calls with is likely dressed casually and taking the call from some room in their home. We’ve seen each other badly in need of haircuts. Then, in some cases, with bad haircuts that we did ourselves or let family members do to us. And we’ve grown familiar with each other’s living spaces, pets, and sometimes family members. I know the view outside of one colleague’s window, the clock on the wall behind another and I always admire the piece of art behind my colleague in Austin. Except for the occasional vacation house rental for a week or two, we’ve all been working out of our homes, living a more lockdown, limited version of the work-life we lived before. It made sense to stay put while lockdown was at its peak. But as it eases up, at least in some places, and while its clear that office life isn’t going back to normal anytime soon, is there a different, new way to live and work?

I’ve telecommuted from home for many years now. Before COVID-19, I would rarely turn my camera on when I was on video chats. And if I did, I’d make sure to put makeup on and look somewhat professional and put together from at least the waist up. But since lockdown started in March, I now turn my camera on for almost every video call and I don’t bother to put makeup on or to change my clothes from whatever ratty t-shirt I happen to be wearing. And I don’t care. I sit in my armchair au natural, secure in the knowledge that everyone I’m on calls with is likely dressed casually and taking the call from some room in their home. We’ve seen each other badly in need of haircuts. Then, in some cases, with bad haircuts that we did ourselves or let family members do to us. And we’ve grown familiar with each other’s living spaces, pets, and sometimes family members. I know the view outside of one colleague’s window, the clock on the wall behind another and I always admire the piece of art behind my colleague in Austin. Except for the occasional vacation house rental for a week or two, we’ve all been working out of our homes, living a more lockdown, limited version of the work-life we lived before. It made sense to stay put while lockdown was at its peak. But as it eases up, at least in some places, and while its clear that office life isn’t going back to normal anytime soon, is there a different, new way to live and work?

We are not dead yet. Battered a little, yes. Frustrated, anxious, wondering about our jobs, our neighborhoods, our schools, absolutely. Definitely not dead.

We are not dead yet. Battered a little, yes. Frustrated, anxious, wondering about our jobs, our neighborhoods, our schools, absolutely. Definitely not dead.

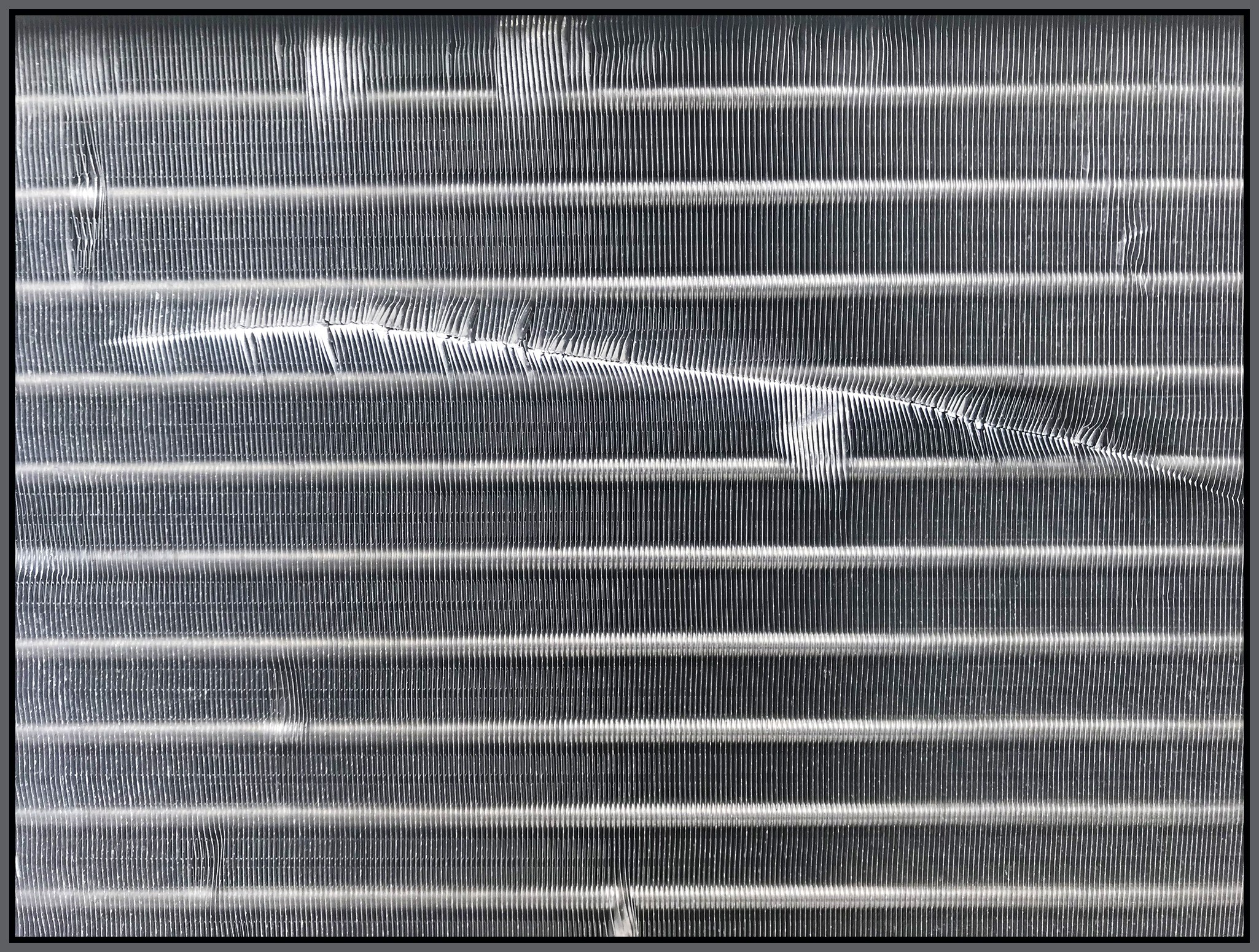

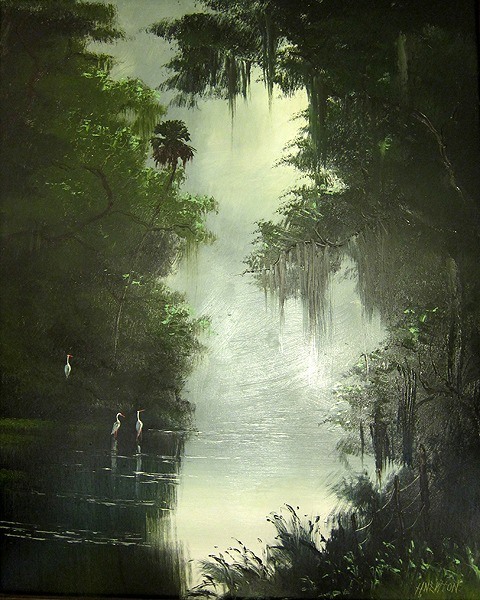

Harold Newton. Untitled, 1960s.

Harold Newton. Untitled, 1960s.

researchers, as well. Indeed,

researchers, as well. Indeed,