by Carol A Westbrook

The smoke of a thousand campfires… That’s what you’d find 600 years ago in the Wyoming Valley of Northeastern Pennsylvania, now the site of Wilkes-Barre and a couple of dozen smaller cities and towns. At the time Columbus visited America, the First People were comfortably settled in this area, which was a permanent home for many tribes, and a winter home for others. The name of this beautiful valley, Wyoming, comes from the Lenape name meaning “at the big flat river.” The big flat river referred to was the Susquehanna, which itself is named for the Susquehannock Indians, who lived along its banks. The Susquehanna is the longest non-navigable river in the US, providing little in the way of commerce and transportation for anything but small boats and canoes.

Don’t get the idea that it was all peace and harmony in the valley. There was friction among the various tribes of Indians, as incoming colonists of the 1700’s competed for resources, while displaced East Coast tribes who were moving in to the area threatened others. The migrating East Coast tribes were primarily Algonquin: Lenape, Delaware, Mahican, Shawnee, and Mohican; they, in turn, displaced the Susquehannock and Nanticoke Indians, peaceful tribes who lived quietly along the river.

And it wasn’t just the native tribes who were threatened. There was also conflict between settlers, as those from Connecticut (Yankees) fought those from Pennsylvania (Pennamites) for land each felt belonged to them, having been included in each colony’s original charter, due to oversight and inadequate surveying. These little-known conflicts, known as the Yankee-Pennamite Wars, were easily as bloody as any of the Indian battles. Fighting continued into the Revolution, though surprisingly both sides agreed to a truce so they could unite to fight the British. Even more surprising is that the conflicts were resolved after the resolution in the courts of law in the new United States of America, without a further drop of bloodshed. Among the few historic markers I found were two markers along the Susquehanna River marking the sites of the Connecticut and Pennsylvania fort, and they are only one quarter of a mile apart!

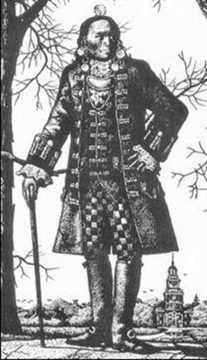

What piqued my interest in the early history of the Wyoming Valley was another historic marker. This one was posted on a lot adjacent to that of my newly-purchased house in central Wilkes-Barre, near the Susquehanna River, at the site of the home of chief of the Delaware, Teedyuscung. Teedyuscung, who died in 1763, was an Indian chief of the Delaware tribe, and by all accounts he was an educated, baptized, and civilized man, known as a great peacekeeper. He was also a dandy in fancy European dress, as you can see. He was killed when his cabin was burned down by enemies.

Like many of the current residents of Wilkes-Barre, I viewed the early Indians as groups of uneducated, uncivilized tribes who were eventually displaced by the Europeans, leaving only place names and relics such as arrowheads, and a few burial sites. After discovering Teedyuscung I changed that perception. I learned that each tribe was unique, each with its own culture, language, and political agenda. Many of the people, like Teedyuscung, were educated and adopted European ways and dress. And these native tribes didn’t just leave; they were forcibly removed by a succession of wars, broken treaties, and genocidal acts. It is a sad and shameful part of the Valley’s history that they our native tribes were treated this way. Perhaps the worst genocidal act was Sullivan’s march.

Sullivan’s march was an incident which occurred during the American Revolution ostensibly in retaliation for the Wyoming Massacre of July 3, 1778. In the Massacre, 360 American patriots, including women, children, and untrained militia, were slaughtered at Forty Fort on the Susquehanna by a ruthless attack of loyalist troops and Mohican Indians, who had allied with the British.

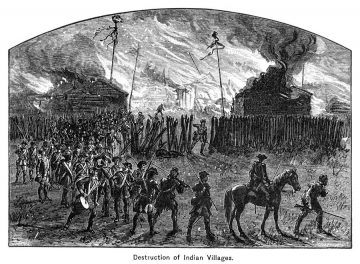

General Washington ordered General Sullivan, later joined by General Clinton, to eradicate the Indian settlements. His orders of May 31, 1779 read,

“The Expedition you are appointed to command is to be directed against the hostile tribes of the Six Nations of Indians, with their associates and adherents. The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements, and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more.”

It is hard to believe that General Washington ordered a scorched earth campaign against the Iroquois without any heed of surrender. Most of the settlements contained only women and children, living at subsistence level. Sullivan’s campaign left hunger and devastation. Many Indians died in the harsh winter of 1779, while others fled to Canada.

Many area residents still feel that this genocide was a justifiable act of war, a retaliation for the massacre at Fort Wyoming. The fact that this retaliation did not include loyalist settlers, but was directed toward defenseless women and children, did not matter. The bravery and sacrifice of the Forty-Fort settlers is remembered every year by a parade of the local residents, but no thought is given to the fate of the Indians, whose slaughter was clearly an act of genocide

Retaliation aside, it was an excuse for Washington to carry out his plans for clearing the land of native tribes to make room for the European settlers. His policy was to acquire Indian lands, by purchase or war. In that he succeeded.

Soon the Valley, and much of the Eastern US, was free of native Americans. The Revolution was over. The Yankee-Pennamite Wars were resolved. Finally there was peace in the Valley, which has lasted to the present day. The War of 1812 and the Civil War bypassed the Wyoming Valley. Though the Valley has abundant food, coal, and even iron nearby, there was no easy way to move these supplies. The Susquehanna River was not of strategic importance as it was unnavigable and could not be used for transport of goods or people, and thus the wars bypassed the area.

However, the Susquehanna played another vital role in transportation–as a part of the Underground Railroad. This shallow river flows from New York to the Chesapeake Bay, and can only be travelled by small boat or canoe. It provides a route for runaway slaves from Baltimore, Maryland, travelling upriver, into the free states of Pennsylvania and New York. It has been estimated that as many as 1,000 runaway slaves passed through Pennsylvania without one apprehension. It is likely that many of their descendants still live in Wilkes-Barre.

The Underground Railroad is another forgotten piece of Wilkes-Barre history. Passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 permitted the forced retrieval of runaway slaves, who would otherwise gain their freedom if they reached a free state, such as Pennsylvania or New York. There was a force of federal commissioners who had the power to pursue these fugitives and return them to their owners, even if they had been free for many years. These commissioners had the right to compel citizens to cooperate with the law.

William Gildersleeve was a pivotal feature in the Underground Railroad in Wilkes-Barre. He was the son of a minister of the First Presbyterian Church, which still stands in downtown Wilkes-Barre. William opened his house on North Franklin street as a station on the Underground railroad, hid them in the kitchen, and at night he shuttled them by wagon to underground stations in Montrose, Scranton and Abington, aided by two fugitive slaves, Lucy Washburn, a maid, and Jacob Welcome a laborer.

At this time, the population of Wilkes-Barre numbered 2,723 residents, of which 121 were blacks. The white population was tolerant of free blacks, but the majority of residents opposed emancipation, fearing the economic disruption it would cause. A document supporting slavery was advanced by Wilkes-Barre’s Democratic Party in 1852 and signed by a number of prominent Wilkes-Barre residents, including owners and operators of the coal mines. Other white citizens feared job competition, and most complied with the fugitive slave law. Harboring slaves was a dangerous undertaking. William Gildersleeve was willing to take the risks.

The only historic marker in town I could find was one near Gildersleeve’s house on East Ross Street, it reads,

“Prominent merchant and ardent abolitionist significant to the Underground Railroad in Wilkes-Barre. He provided refuge to fugitive slaves at his home and business near here. In 1853, Gildersleeve testified in a U.S. Supreme Court case, Maxwell vs. Righter, in which a fugitive, William Thomas, was shot and wounded by deputy U.S. marshals. The case and his testimony received national attention, especially in African American newspapers.” What I find most surprising about the Underground Railroad in Wilkes-Barre is the silence. Like Sullivan’s March, it is barely acknowledged or celebrated in remembrance. There are no tours, no unique museums, few books written.

In a couple of weeks we will celebrate Columbus Day, now known as Indigenous Peoples’ Day. We are learning to re-interpret “history” to take into account the contributions of native Americans and the black populations, often-overlooked groups of people who helped to build the towns of the Wyoming Valley in addition the more widely-celebrated European immigrants who settled here in later centuries to work in the mines. Like much of America, we are coming to recognize that the Valley was built on diversity. And diversity continues, as we acknowledge a strong and willing workforce of newer immigrants including people of color, African Americans, native Americans, Latinos, Europeans and Asians. Many are immigrants from other states, or other countries. All are willing to contribute to the wealth of the town, and deserve acknowledgment and pride.

The Mohicans have the last word. They are extracting their just revenge on the pockets of residents and visitors to the Wyoming Valley at the Mohican Sun, their casino and hotel complex near the banks of the Susquehanna.