by Callum Watts

by Callum Watts

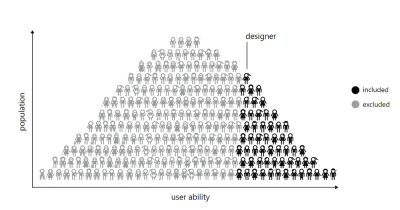

Do identity politics and intersectionality clash with the idea of universal principles? There seems to be a rift emerging in left wing politics around precisely this point. On the one hand various organised identity groups are making it increasingly difficult to ignore the real effects of institutionalised prejudice on their lives. It seems like it’s only through the elevation of particular identities that these interests will be protected, and certain progressive goals reached. These movements reproach, often correctly in my view, the champions of universal rights and freedom as being coded as white, cis, able bodied and male. On the other hand there is a real concern that the elevation of particular identities prevents solidarity between different groups who have otherwise shared interests. This seems to be happening top down as politicians seek to exacerbate these identity markers to consolidate their supporters, and also bottom up as individuals see solidarity as being limited to others who belong to their own perceived identity groups.

It’s worth noting that these two views do not logically contradict each other. It is possible that identity based organising is key to raising the visibility of and guaranteeing rights for certain groups, whilst it also being true that doing this can inflame tensions between different groups and obscure shared interests. Whilst this is to be expected in the broader culture war between left and right, in progressive left circles this division is causing both soul searching, and increasingly, acrimony. There appears to be a reaction against identity politics coming from both the far left and the centre left. If we can ignore the concern trolling (of which there is undoubtedly a lot), the centre left seems to worry about losing the centre ground to a right wing movement that is co-opting the language of universal rights. From the far left we see the worry that identity politics undermines the possibility of a class politics which aims at redistribution. Read more »

“Battle of Algiers”, a classic 1966 film directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, seized my imagination and of my classmates as well when it was shown three years later at the Palladium in Srinagar. A teenager wearing bell-bottoms, dancing the twist, I was a Senior at Sri Pratap College, named after Maharajah Pratap Singh, a Hindu Dogra ruler of Muslim majority Kashmir.

“Battle of Algiers”, a classic 1966 film directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, seized my imagination and of my classmates as well when it was shown three years later at the Palladium in Srinagar. A teenager wearing bell-bottoms, dancing the twist, I was a Senior at Sri Pratap College, named after Maharajah Pratap Singh, a Hindu Dogra ruler of Muslim majority Kashmir. I remember as a child watching the made-for-tv movie

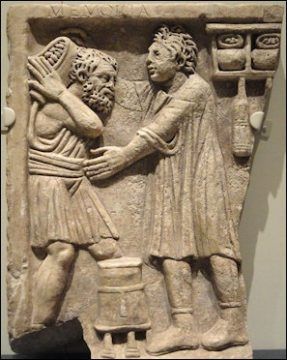

I remember as a child watching the made-for-tv movie  Whether or not a certain line of work is shameful or honorable is culturally relative, varying greatly between places and over time. Farmers, soldiers, actors, dentists, prostitutes, pirates and priests have all been respected or despised in some society or other. There are numerous reasons why certain kinds of work have been looked down on. Subjecting oneself to the will of another; doing tasks that are considered inappropriate given one’s sex, race, age, or class; doing work that is unpopular (tax collector); or deemed immoral (prostitution), or viewed as worthless (what David Graeber labelled “bullshit jobs”), or which are just very poorly paid–all these could be reasons why a kind of work is despised, even by those who do it. One of the oldest prejudices though, at least among the upper classes in many societies, is against manual labour.

Whether or not a certain line of work is shameful or honorable is culturally relative, varying greatly between places and over time. Farmers, soldiers, actors, dentists, prostitutes, pirates and priests have all been respected or despised in some society or other. There are numerous reasons why certain kinds of work have been looked down on. Subjecting oneself to the will of another; doing tasks that are considered inappropriate given one’s sex, race, age, or class; doing work that is unpopular (tax collector); or deemed immoral (prostitution), or viewed as worthless (what David Graeber labelled “bullshit jobs”), or which are just very poorly paid–all these could be reasons why a kind of work is despised, even by those who do it. One of the oldest prejudices though, at least among the upper classes in many societies, is against manual labour.

A life in which the pleasures of food and drink are not important is missing a crucial dimension of a good life. Food and drink are a constant presence in our lives. They can be a constant source of pleasure if we nurture our connection to them and don’t take them for granted.

A life in which the pleasures of food and drink are not important is missing a crucial dimension of a good life. Food and drink are a constant presence in our lives. They can be a constant source of pleasure if we nurture our connection to them and don’t take them for granted. At the beginning of our story—paraphrased from an origin story remembered by a

At the beginning of our story—paraphrased from an origin story remembered by a  There is a minor American myth about shame and regret. It goes like this.

There is a minor American myth about shame and regret. It goes like this. The most charitable, forward-looking take on the science wars of the 90s is Stephen Jay Gould’s, in The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister’s Pox (2003), a delightful book about dichotomies between the sciences and humanities. His diagnosis is primarily that scientists have taken too literally or too seriously some fashionable nonsense, and overreacted; and if everybody can just calm down already, things will be alright and both sides could “break bread together” (108). Gould saw the science wars themselves as a marginal and slightly comical skirmish, almost a mere misunderstanding. “Some of my colleagues”, he said,

The most charitable, forward-looking take on the science wars of the 90s is Stephen Jay Gould’s, in The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister’s Pox (2003), a delightful book about dichotomies between the sciences and humanities. His diagnosis is primarily that scientists have taken too literally or too seriously some fashionable nonsense, and overreacted; and if everybody can just calm down already, things will be alright and both sides could “break bread together” (108). Gould saw the science wars themselves as a marginal and slightly comical skirmish, almost a mere misunderstanding. “Some of my colleagues”, he said, Sughra Raza. Light As a Feather. Boston, Sept 2020.

Sughra Raza. Light As a Feather. Boston, Sept 2020.