by Jeroen Bouterse

The most charitable, forward-looking take on the science wars of the 90s is Stephen Jay Gould’s, in The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister’s Pox (2003), a delightful book about dichotomies between the sciences and humanities. His diagnosis is primarily that scientists have taken too literally or too seriously some fashionable nonsense, and overreacted; and if everybody can just calm down already, things will be alright and both sides could “break bread together” (108). Gould saw the science wars themselves as a marginal and slightly comical skirmish, almost a mere misunderstanding. “Some of my colleagues”, he said,

The most charitable, forward-looking take on the science wars of the 90s is Stephen Jay Gould’s, in The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister’s Pox (2003), a delightful book about dichotomies between the sciences and humanities. His diagnosis is primarily that scientists have taken too literally or too seriously some fashionable nonsense, and overreacted; and if everybody can just calm down already, things will be alright and both sides could “break bread together” (108). Gould saw the science wars themselves as a marginal and slightly comical skirmish, almost a mere misunderstanding. “Some of my colleagues”, he said,

“have become legitimately disturbed by a few truly silly and extreme statements from the ‘relativist’ camp, largely made by poseurs rather than genuine scholars, and have mistaken these infrequent sound bites of pure nonsense for the center of a serious and useful critique. Then, falsely believing that the entire field of ‘science studies’ has launched a crazed attack upon science and the concept of truth itself, they fight back by searching out the rare inane statements of a few irresponsible relativists […] and then presenting a polemic defense of science, ultimately helpful to no one”. (99)

Gould saw an example of such “windmill-bashing” in P.R. Gross and N. Levitt’s Higher Superstition: The Academic Left and Its Quarrels with Science (1994). He also saw it in Alan Sokal’s famous hoax: a brilliant and funny parody, which Gould thought did not really prove much beyond the laziness of the editors that he hoodwinked.

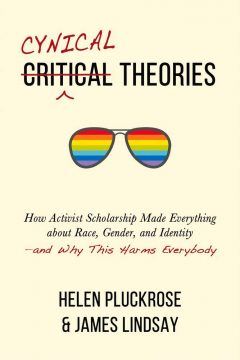

I thought a lot of these 1990s events when I bumped into their 21st-century descendants: first, the ‘Sokal squared’ hoax two years ago, which insisted on taking all the fun out of Sokal’s joke by multiplying it twentyfold. And now Cynical Theories, the equivalent of Higher Superstition, in which two of the same three authors aim their lance at what they perceive to be the heart of intellectual evil: postmodernism. Postmodernism denies reality and universal truth, and thinks that all categories and concepts are therefore functions of group power. These core postmodern motifs have developed (like a “fast-evolving virus”) into actionable left-wing ideas, in the form of a proliferation of cynical, pessimistic and anti-enlightened theories in fields such as gender studies and queer studies.

Like Higher Superstition, Cynical Theories treats postmodern attacks on truth, reality and reason as problems of the left. To their credit, the authors preface this by stating for the record that they have no sympathy for identitarian right-wing nonsense either; they just happen to have turned themselves into experts on identitarian left-wing nonsense. They do think that racism, sexism and bigotry are problems that need to be addressed; just not like this. These protestations of progressive ideals are typical of the genre: we rationalists are so, so eager to join the fight for social justice; how tragic, then, that we are being kept from it by people who spell that term with capital letters. We want to be on your side, but you are making it too difficult with all the woke insanity.

Sokal, too, insisted that of course he was very much committed to left-wing ideals, just not the intellectually repugnant forms they took in the present. “I confess that I’m an unabashed Old Leftist who never quite understood how deconstruction was supposed to help the working class”, he boasted. So how was his elaborate fake article about quantum gravity in an esoteric non-peer-reviewed journal supposed to help the working class, you may ask? Well, because of its role in the political battle against subjectivism, and against postmodernist discourse that insisted “that all ‘facts’ claiming objective existence are simply intellectual constructions.”

This is always the diagnosis, and it sounds suitably principled: yes, no, of course we have to be tough-minded about truth and truthfulness. The authors of Cynical theories keep circling back to that fortress of common sense: postmodernism says that truth is a group construct, and we just can’t have that kind of talk. If we start distinguishing between “my truth” and “your truth”, the authors reason, we get irresolvable social divisions – irresolvable because without appeal to objective reality there can be no bridge between these truths. We are expected to agree that this is dangerous, and so the silliest things can be seen as part of a movement to undermine Western culture, as long as they indirectly betray a tendency towards postmodern relativism. My favorite point in the book is where, without any apparent sense of lack of proportion, the authors refer to an article in the Intersectional Feminist Journal of Politics as an example of “threats to society”, because the article talks of decolonizing hair.

It’s remarkable how much power all these authors ascribe to language. It seems never to occur to them that if social divisions come with incompatible truth-claims, it may be the social divisions that are prior. The authors of Cynical theories see the recent movement in the West to remove imperialist representations from the streets as flowing directly from postcolonial Theory and thus as a clear instance of postmodern anti-Western madness; they never even stop to consider the real facts that this movement may be responding to. Behind left-wing activism they see only discourse and no reality.

I realize, however, that pointing out the irony here does not amount to a rebuttal of the normative argument that, given the existence of different interests, we need to believe in Truth and Reality in order to keep the peace. Perhaps this is an inescapable conceptual truth. Perhaps whoever uses the phrase “my truth” must a priori, without regard for context and without further exercise of judgment, be regarded as a threat to enlightened discourse. The authors codify this belief in a solemn catechism at the end of the book:

“We deny the worth of any scholarship that dismisses the possibility of objective knowledge or the importance of consistent principles and contend that that is ideological bias, rather than scholarship.”

Do people do this – dismiss the possibility of objective knowledge? Gould might have seen this whole line of thought as an inadvertent straw-man, because according to him, metaphysical radicalism was a fringe phenomenon even in the assertive science studies of the 80s and 90s. This may be slightly too easy. Though Gould turned out to be right about the long-term benefits that a more independent and historicizing perspective on science could have, he may have underestimated how relativistic some of the most central voices in science studies were at the time.

How dangerous are relativists and skeptics, then? We need to make a few distinctions here. For example, the authors of Cynical Theories need us all to know that obesity is unhealthy. They read into the body positivity movement a lack of respect for scientific discourse, citing protests against slim advertising models as evidence. This phenomenon is obviously a long way from supporting their point, and is actually compatible with at least three attitudes. In descending order of likelihood: a protester could accept as medical fact that obesity is unhealthy but, in determining their opinion about ‘beach body ready’ posters, weigh this against other facts; they could claim that the medical facts are actually different; or they could, I suppose, deny the existence of medical facts altogether and argue that medical facts are mere group constructs anyway. Only the last of these attitudes would mean that the protester in question is appealing to ‘postmodern’ ideas, as defined by the authors.

I wonder which of these three cases would be most problematic to the authors. I expect that they think that the last case is the worst, because someone who believes in evidence-based medicine can in principle still be convinced if presented with the right data, while someone who denies the very possibility of scientific truth places themselves out of the very conversation. This is in line with their insistence that we need objective truth as a normative ideal in order to build bridges between different perspectives.

This interpretation holds water if we believe that not only are unsympathetic politics driven by willful ignorance about basic facts, but that this is in turn justified by epistemic relativism. The last link in the chain is particularly weak. People can very well be stubborn in their ignorance while buying into philosophical realism, and they can be very open to persuasion by evidence even though they don’t contextualize this evidence in a realist way. The authors’ idea that we can have no peace without scientific realism is like the Christian apologist’s insistence that we can have no morality without God: it has some initial plausibility, but the contrary has already been abundantly proven in practice. Relativists can talk to other people peacefully, and they can build bridges as well as the next person.

Concepts such as truth or objectivity do not suddenly lose all meaning if we regard them as part of social and cultural discourse rather than as somehow standing outside it. They are tricky, but in many contexts they encode attitudes worth spreading. However, like all powerful words, they are open to overstretch and abuse, which may justify resisting their rhetorical force in certain contexts. Postmodern ideas provide a language in which to express such resistance; they do not force those that use this language to have only skeptical and relativistic political opinions, let alone anti-scientific ones. Left-wing opinions on climate change show that progressives are also perfectly capable of appealing to scientific truth, fact and reality.

The authors of Cynical Theories ignore that the same people appeal to our shared humanity, to the reality of a common world, and to plain old scientific fact when campaigning about this and other global issues, while in other contexts they may point out the importance of other identities and the social construction of cultural beliefs. The authors want to read into all left-wing political attitudes they dislike a deep-rooted illiberal, anti-humanist, anti-universalist and anti-enlightened core, but the deep roots prove elusive. To this extent, they are indeed fighting windmills.

We can, however, read their book in another, slightly more charitable and forward-looking way. In their attempts to trace the origins of different “cynical theories”, the more calmly argued parts of the book can serve as a reminder that the amalgam of ideas, intuitions, analyses and morals that constitute what we now intuitively recognize as wokeness has a history, and that it was not always the inevitable, natural unity that not only its detractors but also its adherents sometimes make it out to be. Our current sensibilities are informed by social and political realities, but they are also shaped by cultural modes of interpreting and analyzing these realities. This point, I believe, stands, and even if the authors are hostile chroniclers of it, their attempt at historicizing the ‘social justice metanarrative’ is a valid enterprise. Honest recognition of the historical contingency of our own discourses would serve us well. A little more postmodernism won’t hurt.