by Thomas O’Dwyer

The enigma of the castaway existed long before Robinson Crusoe was published 300 years ago in April 1719, but nothing had ever enthralled the growing reading public of his time like Daniel Defoe’s now classic novel. And, thanks to Defoe, the curse of the desert-island cartoon remains with us – a circular sandbank, a palm tree, a ragged castaway. All that’s required is for a New Yorker magazine funnyman to append an enigmatic or incomprehensible caption. The castaways too – sometimes called Robinsonades but don’t encourage it – are still with us. Tom Hanks communes with a volleyball in a film named, yes, Cast Away, and Matt Damon goes one-up on him in The Martian by claiming to be “the first person to be alone on an entire planet.” New movie variants on the theme have been released almost every year since the 1954 Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, Luis Buñuel’s first colour film.

So who reads the original Robinson Crusoe today? This book has been called the first English novel, or imperialist propaganda, or a textbook of capitalism. Since the nineteenth century, it has been a children’s book – more specifically, a boys’ adventure book, sitting on the same shelf as Treasure Island. A cursory search of Amazon’s statistics yields a surprise. Among many editions still on sale, the novel ranks number 358 in the Classic Action & Adventure genre, number 615 in Children’s Classics, and number 202 in the Kindle store’s Fiction Classics. Those are impressive rankings for an archaic seafaring tale that was first published 103 years after the death of William Shakespeare.

In academia, Robinson Crusoe has long been part of the debate on the origins of the first English novel. Of course, in Western literature, Don Quixote is the outstanding claimant, but Crusoe did set up the English narrative structure that authors have riffed on ever since. When Crusoe’s ink supply runs out on the island, the author noticeably transitions from writing a journal to crafting a novel. John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress was published forty years before Crusoe and was probably the last fictional, albeit devotional, work approved of by the various churches. After Crusoe came the deluge – Moll Flanders, Fanny Hill, Tom Jones, Vanity Fair, and hundreds more. To hell with devotion. The novels teem with flawed and moral castaways who must find salvation within themselves, if ever.

Crusoe is at least the first realistic novel. No one can dispute its importance in the history of world literature or its durability in the popular cultural imagination. It is still surprisingly readable, with a captivating rhythm that is most apparent in some of the audio recordings that are now available. It is a story with a complex and compelling plot, high drama and an emotional impact. It introduced many techniques of novelistic realism – journal entries, descriptions of scenery, quotidian details and believable narratives of its characters’ thinking. Before Defoe, the thoughts of such ordinary people as a sailor and a native American tribesman would not have been deemed worthy subjects for literature.

Of course, there are the jarring elements of the world three hundred years ago that a modern reader must glide past. There is slave trading, cannibalism, the invisibility of half the world’s population. (Of his life after his rescue from the island, Crusoe tells us that he “married a woman.” We know his parrot’s name was Poll, but his wife didn’t merit a name, much less a description). So the book is rife with the assumptions of its time and slavery is fine so long as you convert the savages to Christianity.

As the plot and his battles against adversity carry us along, it is easy to miss that fact that this Crusoe, whose name has been known around the world for 300 years, is a pretty dull fellow. Adventure seems to be his aim, but mediocrity and the accumulation of stuff is his practice. He refers again and again to his father’s Goldilocks philosophy of life, which he admires. “My Father bid me observe it, and I should always find that the calamities of life were shared among the upper and lower classes of mankind; but that the middle station had the fewest disasters, and was not exposed to so many vicissitudes as the higher or lower part of mankind.”

Daniel Defoe was nearly 60 when the novel was published and even he was amazed by its success. Four English editions rolled off the presses and translations into French German, Dutch and Russian followed. The full title of the first edition probably qualifies as flash fiction – a story in itself: The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, Of York, Mariner: Who lived Eight and Twenty Years, all alone in an Uninhabited Island on the Coast of America, near the Mouth of the Great River of Oroonoque; Having been cast on Shore by Shipwreck, wherein all the Men perished but himself. With An Account how he was at last as strangely deliver’d by Pyrates. Written by Himself.

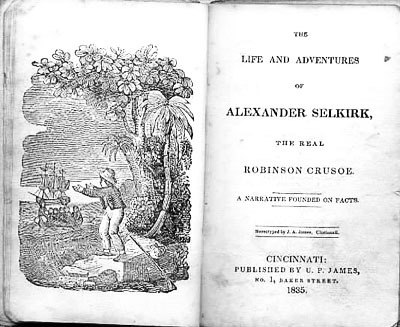

At the heart of the novel is an intersection of three associated characters – Alexander Selkirk, Defoe and Crusoe. In a time of booming sea traffic and multiple shipwrecks, there were plenty of real-life castaway stories Defoe could have drawn on. The most likely was the experience of the Scottish sailor Alexander Selkirk, who spent four years on an uninhabited island in the Juan Fernandez atoll, off Chile. He asked to be put ashore there, after refusing to continue a voyage on a leaky ship. (The ship later sank). Selkirk, the son of a tanner, was unpleasant and quarrelsome from a young age. He eventually went to sea on a pirate ship that preyed on merchant vessels of England’s enemy Spain.

Unlike Crusoe’s island, Selkirk’s was reasonably abundant and he survived at a basic level of existence, making no great effort to improve his situation. An English vessel rescued Selkirk in 1709 and, in 1712, members of the expedition which rescued him published his adventures in A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World and A Cruising Voyage Around the World. His experience mellowed him and the captain who rescued him wrote: “One may see in him that solitude and retirement from the world is not such an insufferable state of life as most men imagine.” The calm didn’t last. Back in England, Selkirk was charged with assaulting a shipworker and was jailed for two years. He returned to a pirate ship and died of yellow fever off the west coast of Africa in 1721. He was buried at sea. In 1966, Chile renamed the Juan Fernandez island as Robinson Crusoe Island – somewhat confusing, since it was Selkirk who was marooned there. The fictional Crusoe was shipwrecked on an unnamed Caribbean island north of Venezuela.

The author Daniel Foe was the son of a London candle-maker. He was a lifelong hack, a hopeless entrepreneur, and a bankrupt. His failed schemes included selling marine insurance (during a war), breeding civet cats, collecting taxes on glass bottles and making tiles and bricks. He changed his name to Defoe to imply a higher social status. Mercantilism was the rising economic force in his time, generating a new spirit of capitalist individualism which is clearly reflected in his and Crusoe’s characters. Defoe produced more than 600 journals, pamphlets and books under many pen names, and for years published The Review, a weekly journal. Robinson Crusoe was his outstanding success, and he capitalised on it with two follow-ups – in 1719, The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, and in 1720, Serious Reflections During the Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe.

He also had some success with two picaresque novels, Moll Flanders and Roxana, but he accumulated massive debts all his life and was often imprisoned for it before his death in 1731. Filtered through Defoe, there is a crucial difference between the real and fictional castaways. Selkirk was a buccaneer, ruthlessly looting and raiding coastal settlements. The economic philosophy of the Crusoe book is the opposite. Pirates raid, loot, rape and frequently drink themselves to death on their takings. Not Robinson – he’s your capitalist imperialist; his world, even in miniature, is one of trade, exploitation and profit. He’s the master of his own domain and Friday, the only other human he meets on the island, is told to call him “Master.”

Now, what on earth has this fiction about a dull merchant stuck on an island got to do with 2019? In one of the masses of scribblings marking the book’s anniversary, The Guardian’s Charles Boyle wrote an article titled Robinson Crusoe at 300: Why it’s time to let go of this colonial fairytale. He wrote: “Defoe’s book has inspired novels, Hollywood movies and games – but the shipwrecked slave-trader should never have become a role model.” But for whom is he a role model? Could it be the white male imperialist capitalist who demeans women and thinks people of colour are savages? Aha! Yes, let’s ditch that one.

And yet, a digitized Robinson Crusoe is now wafting through the cloud. A Google search for the word “Crusoe” returns 18 million hits covering every imaginable topic far beyond books and movies. Now it is most often listed as a children’s book. (Even in the nineteen century, women authors started to write stories of girl Crusoes for the sisters of the little imperialists). Over the years, almost any person of opinion has had something to say about the book and the academic papers would fill a warehouse.

Virginia Woolf said Robinson Crusoe was so ubiquitous that it was “one of the anonymous productions of the race rather than the effort of a single mind”. The American comic writer Will Cuppy mocked Crusoe’s supposed survival skills: “Most people, it seems, think that Robinson Crusoe when he landed on his island had nothing to keep him from starvation or anything else. As a matter of fact, he had twelve raft loads of supplies that he took off the wrecked ship. He had as much food and furniture as if he had had a delicatessen store and Fifth Avenue outside his hut.”

Ah yes, sneered Carlos Fuentes, “Robinson Crusoe! The first capitalist hero, a self-made man who accepts objective reality and then fashions it to his needs through the work ethic, common sense, resilience, technology, and, if need be, racism and imperialism.” Jean-Jacques Rousseau differed: “There exists one book, which, to my taste, furnishes the happiest treatise of natural education. What then is this marvelous book? Is it Aristotle? Is it Pliny, is it Buffon? No. It is Robinson Crusoe.”

Perhaps the desert-island cartoonists will be the first to let us know when Crusoe’s days are finally done, as The Guardian columnist suggested they should be. After all, they quietly killed off the white explorers stewing in cannibal cauldrons in Africa, and we haven’t seen ragged figures crawling towards a desert mirage for some time. Now that we have satellite maps and GPS, have we not squeezed this castaway meme dry? William Shawn, who edited The New Yorker from 1952 to 1987, once banned desert-island cartoons. But they are still here and everywhere, now incorporating useless email messages in bottles (“You have no new mail”), surveillance cameras on the palm tree, and even bemoaning the lack of Wifi.

![I really feel like such a cliché. [Image: Brier]](https://3quarksdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/toon1-1.png)

Mankoff said the original cartoons portrayed isolation from the restrictions of society, especially the moral strictures of the time. “If a man and a woman were on the island in the 30s or 40s, the cartoon probably has sexual content. The woman might be asking the man, ‘How can I be sure you’re a millionaire?’”

Of course he’s a millionaire; he’s the final culmination of Crusoe capitalism.