by Gabrielle C. Durham

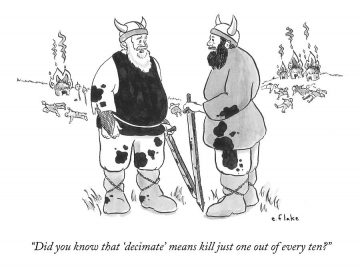

If you took Latin, then you probably have a larger vocabulary than the average bear, and you are more likely to have strong opinions on some words you vaguely remember based on Latin roots (cognates). For example, folks are more commonly using “decimate” to mean destroy or devastate, and it annoys the living materia feculis out of me. Decimate originally meant to kill every 10th person, based on the Latin word for 10 (decem), which is so oddly and satisfyingly specific. “Devastate” and “destroy” are already well known and used, so why do they need another alliterative ally in little weirdo “decimate”?

If you took Latin, then you probably have a larger vocabulary than the average bear, and you are more likely to have strong opinions on some words you vaguely remember based on Latin roots (cognates). For example, folks are more commonly using “decimate” to mean destroy or devastate, and it annoys the living materia feculis out of me. Decimate originally meant to kill every 10th person, based on the Latin word for 10 (decem), which is so oddly and satisfyingly specific. “Devastate” and “destroy” are already well known and used, so why do they need another alliterative ally in little weirdo “decimate”?

Another little sneak is “cleave.” Meaning #1 is to adhere tightly and closely or unwaveringly. Meaning #2 is to divide or split, to separate, or to penetrate a material by or as if by cutting or tearing. The second meaning is where we get “cloven” as in “cloven hoof,” the tool “cleaver,” “cleft” as in “cleft palate,” and “cleavage.” Both versions arose before the 12th century. The first meaning comes from Old English clifian by way of Middle English clevien. The second meaning comes from Middle English cleven from Old English cleofan and likely Old Norse kljufa, meaning to split. How can these words be so close for almost a millennium with polar opposite meanings?

The word “egregious” also has two conflicting definitions, the little dickens. Meaning #1 is remarkably or conspicuously good going back to its archaic meaning of distinguished, as in “Flavio made an egregiously excellent impression on the interviewers at the bank.” Meaning #2 heads in a different direction, as flagrantly bad or shocking. The most common version we would read is the phrase “egregious errors.” Both words have the same root, gargrex, meaning herd or flock, which is also the basis for “gregarious,” meaning volubly sociable. (Similar to the “grammar”/“glamour” connection: Who would have pegged those two words as coming from the same source with such contemporarily incongruous meanings?)

“Nonplussed” can mean surprised and perplexed to the extent that a person is rendered unable to think, do, react, or decide. Its second meaning is unperturbed. The word “nonplus” can be both a noun and a verb because, of course, it can. This linguistic shape-shifter that can mean anything comes from Latin non plus (no more) originating in the 16th century. It probably can stand in for “unicorn,” “washcloth,” or “monocle.” Go ahead and try this ersatz substitution; let me know how it goes.

Another double agent is the verb “peruse,” which means to look or to scan cursorily at a text. This Latinate bad boy is also defined as to examine and read closely and carefully. At least both meanings are transitive, because that would be a whole other pother. “Pother” is an example of many functional meanings crammed into one sausage casing. As a noun, it can mean confused, fidgeting activity; agitated talk over a piece of trivia; a thick cloud of smoke or dust, or mental turmoil. As a verb (transitive) dating back to the late 17th century, it means to put into a pother, and as an intransitive verb, it means to be in a pother. Which pother as a noun is intended in the meaning of the verb? My presumption is the first definition, as a fluttery commotion. That word appears to be quite promiscuous.

Even the slangy British “chuffed” is not immune (should that be mune?). It can mean both very pleased or happy, and it can also mean annoyed or displeased. Both of these adjectival meanings come from the mid-20th century, but the original meaning of “chuff” as a noun to describe a boor or churlish person dates back to the 15th century. The connection over the centuries is not unreasonable.

When in doubt, ask a foreign comedian to really break down the weirdness of English. Watch the Finnish comedian Ismo talk about the word “ass.” It can mean butt, naturally, but it also stands as an intensifier and as a word that can make the word it modifies take an opposite meaning. Who knew this little word was so versatile?

What this all comes down to is that English is psychotic. We have already been scarred by the spelling atrocities, but heaping on the insult of double and triple meanings to orthographic injury just seems needlessly cruel. The sneaky bastards!