by Abigail Akavia

Photo by Gadi Dagon, Courtesy of Batsheva Dance Company

Two weeks ago I celebrated Passover with my family. It was an intimate affair, just four adults and three preschoolers in the small dining room of our rented apartment in Leipzig. Our secular way of life makes Passover, for us, a holiday of light-to-non-existent religious content; nonetheless the richness of the symbolism and of the ritualistic foods is still something we enjoy. Making the Seder palatable to the kids, both the dinner itself and its ritualistic elements, became the central concern for us, their perpetually exhausted parents. The traditional text read in the Seder, the Haggadah, is cryptic in its Aramaic expressions and passages of Talmudic hermeneutics, on which the guests, both young and old, are encouraged to ask questions. But our distaste for the way the myth of Passover resonates in contemporary nationalistic discourse in Israel and elsewhere has brought us to include alternative content in our Seders, stories of other historical struggles towards freedom, which have often been conceived in terms that echo the story of Exodus. This year we read parts of the Hagaddah composed by Rabbis for Human Rights, which was originally read in a detention camp for African refugees in the Israeli desert in 2016, and includes Bob Marley’s Redemption Song. When we lived in Chicago, we told stories of Harriet Tubman and The Underground Railroad.

An Israeli Seder is not dissimilar to American Thanksgiving: a long meal that commemorates the founding of the nation, along with the post-nationalistic reckoning that both holidays can prompt. In both cases, a religious-historical myth becomes incarnated in food. Thus, the matzo, the most important culinary feature of Passover, reminds us of the unleavened bread that the Israelites hastily prepared when they fled their enslaving Egyptians. Every other part of the meal is also meant to symbolize part of the story, that of the Hebrews’ struggle to become a nation. (The series of hardships which the Seder is meant to recall may explain why the Seder meal, while as excessive as a Thanksgiving dinner, is arguably less delicious.)

Our childhood Seders were an elaborate event, an ordeal really. The main feature of the experience was its length, but it was also an exciting ritual with extended family members, for which you get all dressed up. Equally predictable in its fun and boring bits, Seders were always the same. Early on in the evening we read in the Haggadah: Why [Al shum mah] do we eat this matzo? Al shum mah repeats, a catchy turn of phrase in archaic Hebrew, amusing in its foreignness to our colloquial modern language. (Indeed, this year it made my children giggle.) Al shum mah do we eat this haroset, a delicious sticky paste made of fruit and nuts? To remind us of the mortar our fathers used when they worked in construction as slaves in Egypt. Why do we eat this bitter lettuce? Because the Egyptians made the lives of our fathers bitter. Right, of course. It’s a little bit ridiculous. But it’s also virtually the only Jewish text of which I still know parts by heart, having been brought up in an entirely secular household.

This year we did without some of the traditional dishes that are considered staples, chief among them gefilteh fish; also missing from the table was the iconic Seder plate with its shriveled-up chicken wing (“chicken-arm” in Hebrew, placed there to symbolize God’s strength in delivering the Israelites from Egypt) and its hard boiled egg with the greying yolk. No-one remembers what the egg stands for, though as a child the first (and sometimes only) part of your Passover dinner essentially consists of matzo with hard boiled eggs, both equally dry, on which you are allowed to snack while the adults dutifully plough through the reading of the Haggadah. Thankfully, the meal comes in the middle of the ceremonial text rather than its end. In my childhood Seders, we almost never made it to the parts of the Haggadah that come after the meal. However, one of the best-known and most fun Passover songs is found near the very end of the night: Echad Mi Yode’a [Who Knows One]. It is a cumulative song, each verse adding one part and repeating the verses the came before. The song enumerates thirteen principal motifs of Jewish culture from one to thirteen: one God, two Stone Tablets (on which the Ten Commandments were engraved), three Fathers (Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob), four Mothers (Sarah, Rebekah, Leah, and Rachel), and so on. Because of the cumulative structure, the verse “One is our god in heaven and on earth” is sung thirteen times. The song ticks off all the boxes that keep the young ones entertained: a catchy melody, the repetitive lyrics that are sometimes performed progressively faster, and the eponymous question-and-answer participatory nature—Who knows one? I know one! … Who knows two? I know two! Our kids, unsurprisingly, loved it. (As for me, at some point the feeling crept up on me that we should shut the windows lest the noise of us Jews celebrating too loudly upset our neighbors, and on Easter Friday at that. Not that there is much chance that the local Saxons would recognize religious Hebrew songs, but still.)

The next step in our Seder was almost obvious: to introduce the kids to the iconic rendition of Echad Mi Yode’a by Batsheva Dance Company.

A few days later I learned that my parents, whose offspring are spread around the globe and do not fly home for Passover, also held an alternative (gefilte-fish-free) Seder with friends, and spent a part of the evening watching the same youtube video. A family tradition is born.

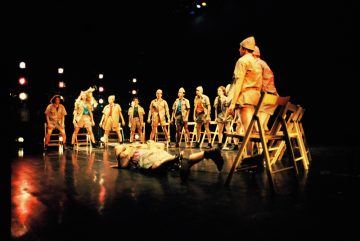

The 7-minute segment was originally part of Kyr [Wall], the first full-length dance piece Ohad Naharin created for Batsheva as the company’s artistic director in 1990, and has been performed countless times since. It appeared in Anaphase [1993], the company’s hugely successful show which toured nationally and internationally all through the ’90s. It was subsequently part of Decadance [2000], a compilation of segments from Naharin’s works from different periods, which reached a similar level of acclaim. It has been performed by other international dance companies as well, including Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Echad Mi Yode’a has reached such fame in the world of dance that it has been ripped off by various performing artists, as in a recent performance in the Country Music Awards and in Chicago-based Lucky Plush’s 2009 Punk Yankees. In both cases Naharin’s work was referenced without credit, though in Lucky Plush’s production, which dealt with sampling and cultural appropriation in the internet age, the move was intentional and self-aware, and there was arguably an expectation that the audience would be at least somewhat familiar with the original.

The iconic status of Naharin’s Echad Mi Yode’a in Israeli culture is of a different dimension. Viewing this piece is a transfixing experience, and especially so for an Israeli Jew. As is often the case with verbal explications of dance, describing the piece will not do it justice. It seems utterly futile to try to delineate in words the actual movement sequence or the quality of Batsheva’s extraordinary dancers (an oft-used adjective, though, is “explosive”). If you’re reading this, I urge you to follow the youtube link above and watch the piece. What can be said of the piece and its core-stirring effect are seemingly obvious things: Here is the incantation-like song which we have known since childhood. It is repetitive. It keeps building up. This chant is the mantra of our cultural existence. It is stripped down to its very essence, but at the same time becomes something else. Stripping down is of course a theme in its own right here. As the dancers ferociously take their suits off and hurl them into the center of the stage, we see their plain grey underclothes. The dissonance between the more stylish exterior shell and the pitiful blandness of the clothing underneath is jarring. Both sets of clothes are similar, though, in how they erase personal identities and force a cohesiveness on the group members. What does peeling the suits off reveal? Who are these suited Jews, moving trance-like on black folding chairs, throwing their limbs all over the place, crying out “One is our god in heaven and on earth”? As my six-year-old asked me, “Why does one of them keep falling down?”

Why indeed.

That Naharin transforms Echad Mi Yode’a from an anthem of Jewish observance into a radical critique of the Israeli nation-state is one way of looking at it. In the earliest version of the piece, the dancers wore khaki work-clothes instead of black and white suits, marking them clearly as Kibbutzniks or pioneer settlers, laborers from the early decades of the Zionist movement in Palestine or the young state of Israel. This identity was continuous with the image created by the sudden appearance of the dancers’ flesh in simple underclothes. Naharin’s later change of costumes allowed for an even more general image of Israeliness to emerge from the work, and one that, moreover, reaches to both before and after the historical moment of early Zionist settlement. The black suits evoke at once (pre-Zionistic) orthodox Jewry and a secular, capitalistic, and cosmopolitan persona. Both stand in contrast to the socialistic ideal of working the soil and building homes with one’s bare hands—in contrast, too, to the physical labor of the dancers performing onstage. But these archetypal Jewish characters, whichever one we choose to see in the piece, are all bound together by their link to the tribe and their relation to the song—which, precisely, embeds this tribal link through ritual music. At each iteration, the dancers stand there, shouting about “our god.” Their identity hovers between religious Jew and Israeli, transforming and dissolving between the two.

Photo by Gadi Dagon, Courtesy of Batsheva Dance Company

Part of what makes Echad Mi Yode’a so powerful, suggests Dr. Tal Kohavi, an anthropologist specializing in Israeli dance, is the versatility of Naharin’s choreography. It could be taken to be dead-serious or lighthearted, seen as fundamentally tragic or as jubilant and celebratory. It is effective when performed by an intimate cast of a handful of dancers; on the large stage of the Israeli Opera House in a gala celebrating Batsheva’s 50th anniversary in 2014, when the piece was performed by dozens of dancers in rows, its ecstatic potential was magnified.

The music that accompanies the dance is performed by Israeli rock band The Tractor’s Revenge (the band’s mere name could suggest the rift between artistic pursuit and the land-tilling ideal of Israel’s early pioneers). Their arrangement, in which Naharin himself participated, was commissioned for Kyr. The pounding drums and the distortion guitar contribute to the escalating ecstasy, and at the same time give it a menacing undertone, a frightening relentlessness. The gravelly tone of the singing voice could not be more Israeli: straightforward and non-beautiful, like singing during military drills. To my eyes (and ears) the soundtrack unavoidably tips the work to a sphere of dread and doom.

This year I was surprised to hear from both my husband and my mother that to them the piece evoked the memory of the Holocaust. I had never before considered this frame of reference for the work, though to a certain extent all Israeli art operates in a post-Holocaust context. To my husband, everything in the work was colored by its Jewishness, including “these folding chairs, like the ones at synagogue.” My mother pointed out the mound of clothing articles that accumulates at the center of the stage: “and the grey underclothes, like prisoners in concentration camps.” Kohavi shares my surprise when I tell her this: “I would have never made that connection on my own, but I see why this association works.” When the outer layer of clothing comes off, the dancers are left with their exposed body in work-clothes, with the suggestion of physical labor taken to the extreme.

And the one that keeps falling down.

In this ecstatic state, in its thrill and danger, its faith and scorn, in its beauty teetering on the edge of the abyss, the group of dancers-chanters returns to its cultural pillars (one God, two Stone Tablets). What Naharin managed to do with his exceptionally suggestive and multivalent interpretation of Echad Mi Yode’a—we can say this now, almost thirty years after it premiered—is to cement his version of the song as another such pillar. And it is now embedded in my family’s Passover tradition, these Jews dancing on the brink of disaster.