by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

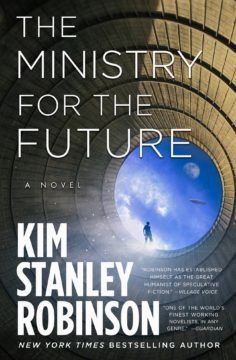

The year is 2025.

Frank, who is an American aid worker living in northern India, is alarmed to wake up one morning to an outside temperature of 103° F with 35% humidity. Things go from bad to worse, when the power grid goes down, and there is no air conditioning. As temperatures climb to 108° F with 60% humidity, people begin dying. They are being cooked to death.

Known as a wet-bulb temperature event, a sustained combination of high temperature plus high humidity exceeding wet-bulb temperature 35 °C (95 °F) will likely cause death, even in a healthy person sitting in the shade with plenty of water to drink.

When things become unbearable, Frank takes refuge with many others in a shallow lake. But the water is too warm –and by morning, everyone in the lake but Frank is dead. He has no idea why he survived –but life will never be the same.

The shock surrounding the event, which saw millions die in Uttar Pradesh, led to the formation of the Ministry for the Future. Part of the United Nation’s Convention on Climate Change, it was founded under Article 14 of the Paris Agreement with an office set up in Zürich.

The people of India are rightly furious. They point out that the Europeans sucked their resources dry for hundreds of years, and by the time they shook free of their colonialist yoke and tried to develop, they were being told by wealthy Europeans that, “Sorry, you are too late to the party. Rising CO2 and all that.” Indian leadership argues that they use far less coal-generated electricity to bring their people out of poverty than the Americans do to live what in America is considered a normal life.

Located in a part of the world that will bear the initial brunt of the crises, India had expected that other members of the Paris Convention would come to their aid.

Drones were seen overhead so the Indian people knew the situation was being monitored, but at the end of the day, they appeared to be left to die.

And so, they decide to take matters into their own hands. Read more »

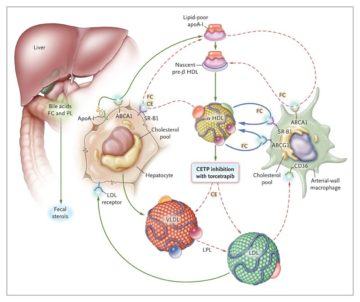

shocking. Torcetrapib, for example, failed at the very end of its phase III trial. So many resources had been expended to get that far in development. Everything spent was lost. All that remained was a big data pile worth virtually nothing, along with pilot plants that were built to supply the drug to thousands of patients across years of clinical trials.

shocking. Torcetrapib, for example, failed at the very end of its phase III trial. So many resources had been expended to get that far in development. Everything spent was lost. All that remained was a big data pile worth virtually nothing, along with pilot plants that were built to supply the drug to thousands of patients across years of clinical trials.

“The American way of life is not up for negotiation.” —George HW Bush to the assembled international diplomats at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, 1992

“The American way of life is not up for negotiation.” —George HW Bush to the assembled international diplomats at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, 1992 Not since the Civil War and Reconstruction has the citizenry in the United States been so divided. In our current

Not since the Civil War and Reconstruction has the citizenry in the United States been so divided. In our current

November 6, 1860. Perhaps the worst day in James Buchanan’s political life. His fears, his sympathies and antipathies, the judgment of the public upon an entire career, all converge into a horrible realty. Abraham Lincoln, of the “Black Republican Party,” has been elected President of the United States.

November 6, 1860. Perhaps the worst day in James Buchanan’s political life. His fears, his sympathies and antipathies, the judgment of the public upon an entire career, all converge into a horrible realty. Abraham Lincoln, of the “Black Republican Party,” has been elected President of the United States.

Back in 1971, I couldn’t have predicted that the release of Joni Mitchell’s fourth album, Blue, would mark the beginning of the end of a friendship.

Back in 1971, I couldn’t have predicted that the release of Joni Mitchell’s fourth album, Blue, would mark the beginning of the end of a friendship.

2020 has been a wild ride, but it’s almost over, and I’m here to tell you it wasn’t all bad, as some great music came out this year – so much, in fact, that we’ll have to have two or even three podcasts this time even for the small taste which is our annual year-end review. Here’s part 1 (widget and link below).

2020 has been a wild ride, but it’s almost over, and I’m here to tell you it wasn’t all bad, as some great music came out this year – so much, in fact, that we’ll have to have two or even three podcasts this time even for the small taste which is our annual year-end review. Here’s part 1 (widget and link below).

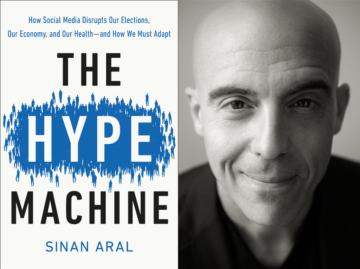

Given where we find ourselves in this late November of 2020, it is hard to think of a book more relevant or timely than The Hype Machine by Sinan Aral. The author is the David Austin Professor of Management and Professor of Information Technology and Marketing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. As one of the world’s foremost experts on social media and its effects, Prof. Aral is the perfect person to look at how this phenomenon has changed the world and the human experience. This is what he sets out to do in his new book, The Hype Machine, published under the Currency Imprint of Random House this September, and with considerable success.

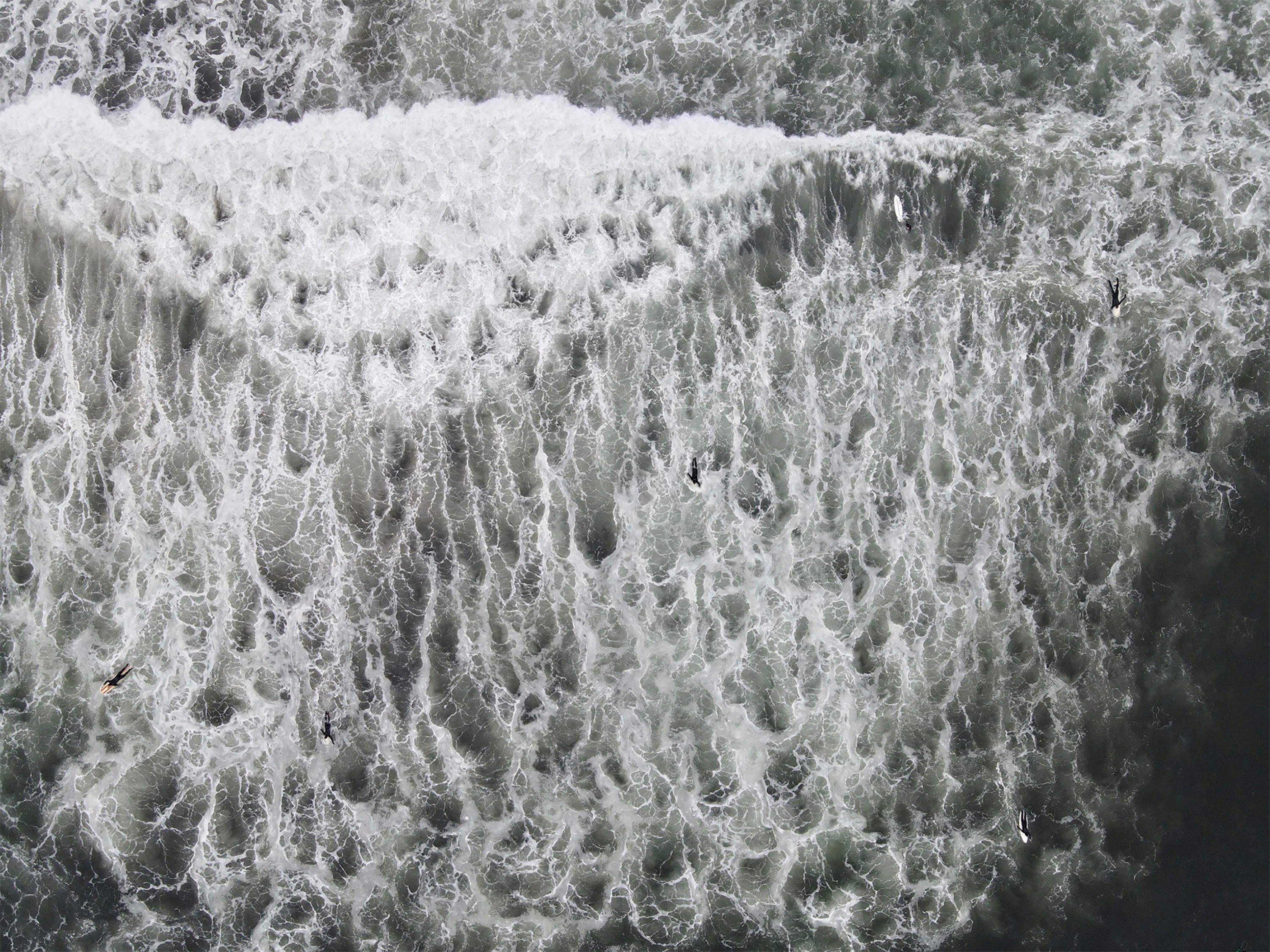

Given where we find ourselves in this late November of 2020, it is hard to think of a book more relevant or timely than The Hype Machine by Sinan Aral. The author is the David Austin Professor of Management and Professor of Information Technology and Marketing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. As one of the world’s foremost experts on social media and its effects, Prof. Aral is the perfect person to look at how this phenomenon has changed the world and the human experience. This is what he sets out to do in his new book, The Hype Machine, published under the Currency Imprint of Random House this September, and with considerable success. Dylan Kwait. Surfers by Plum Island, October 2020.

Dylan Kwait. Surfers by Plum Island, October 2020.

Not long ago there was an article circulating on Facebook about ‘Hating the English’, originally published in a large circulation newspaper. The Irish author says something to the effect that once she thought it was just a few bad ones etc., but now she hates the lot of them. It’s been stimulated, I think, by the repulsive English nationalism that has been raising its head since Brexit, plus the usual ignorance about Ireland, Irish history and Irish interests on the part of your typical ‘Brit’. It’s not a very good piece of writing, and it has a rather slight idea in it. I’d ignore it but for the ‘likes’ and positive comments it’s received, particularly from ‘leftists’. It’s an example of what we could call ‘bloc thinking’ – the emotionally satisfying but futile consignment of entire masses of people into categories of nice and nasty.

Not long ago there was an article circulating on Facebook about ‘Hating the English’, originally published in a large circulation newspaper. The Irish author says something to the effect that once she thought it was just a few bad ones etc., but now she hates the lot of them. It’s been stimulated, I think, by the repulsive English nationalism that has been raising its head since Brexit, plus the usual ignorance about Ireland, Irish history and Irish interests on the part of your typical ‘Brit’. It’s not a very good piece of writing, and it has a rather slight idea in it. I’d ignore it but for the ‘likes’ and positive comments it’s received, particularly from ‘leftists’. It’s an example of what we could call ‘bloc thinking’ – the emotionally satisfying but futile consignment of entire masses of people into categories of nice and nasty.