by Thomas O’Dwyer

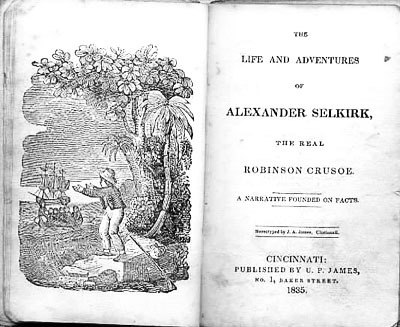

The enigma of the castaway existed long before Robinson Crusoe was published 300 years ago in April 1719, but nothing had ever enthralled the growing reading public of his time like Daniel Defoe’s now classic novel. And, thanks to Defoe, the curse of the desert-island cartoon remains with us – a circular sandbank, a palm tree, a ragged castaway. All that’s required is for a New Yorker magazine funnyman to append an enigmatic or incomprehensible caption. The castaways too – sometimes called Robinsonades but don’t encourage it – are still with us. Tom Hanks communes with a volleyball in a film named, yes, Cast Away, and Matt Damon goes one-up on him in The Martian by claiming to be “the first person to be alone on an entire planet.” New movie variants on the theme have been released almost every year since the 1954 Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, Luis Buñuel’s first colour film.

So who reads the original Robinson Crusoe today? This book has been called the first English novel, or imperialist propaganda, or a textbook of capitalism. Since the nineteenth century, it has been a children’s book – more specifically, a boys’ adventure book, sitting on the same shelf as Treasure Island. A cursory search of Amazon’s statistics yields a surprise. Among many editions still on sale, the novel ranks number 358 in the Classic Action & Adventure genre, number 615 in Children’s Classics, and number 202 in the Kindle store’s Fiction Classics. Those are impressive rankings for an archaic seafaring tale that was first published 103 years after the death of William Shakespeare.

In academia, Robinson Crusoe has long been part of the debate on the origins of the first English novel. Of course, in Western literature, Don Quixote is the outstanding claimant, but Crusoe did set up the English narrative structure that authors have riffed on ever since. When Crusoe’s ink supply runs out on the island, the author noticeably transitions from writing a journal to crafting a novel. John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress was published forty years before Crusoe and was probably the last fictional, albeit devotional, work approved of by the various churches. After Crusoe came the deluge – Moll Flanders, Fanny Hill, Tom Jones, Vanity Fair, and hundreds more. To hell with devotion. The novels teem with flawed and moral castaways who must find salvation within themselves, if ever. Read more »