by Joshua Wilbur

As you read these words, someone (or some thing) could be creeping up behind you.

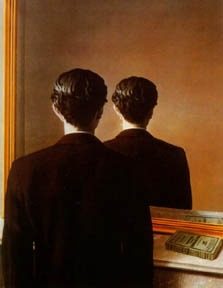

Maybe you’re sitting at your desk. Or at your kitchen table. Or on a half-empty train. Behind you looms an encroaching presence, a silent observer. I picture a middle-aged man in a black suit — a tired and unfeeling assassin— but imagine whatever or whomever you like. A mythical monster, a scorned lover.

Someone might just be there. Right behind you. You won’t know for certain until you look.

* * *

We humans don’t have eyes in the back of our heads. Evolution didn’t budget for that luxury. Some animals—deer, horses, cows—have eyes on the sides of their heads, allowing them a wide field of vision. Other animals—humans, dogs, cats—have their eyes closer together and facing forward, allowing them to better judge depth and distance.

So while grass-grazers enjoy peripheral, panoramic vision their hungry hunters quickly spot them through dense forest. This suggests a simple rule of thumb for distinguishing the skulls of predators from those of prey: “Eyes in the front, the animal hunts. Eyes on the side, the animal hides.”

Eyes in the back, though, would require too many complex mutations, and we do well enough craning our necks to find food. Our bodies have been molded over millions of years to fulfill carnal desires, desperate for what’s in front of us: arms stretching out, noses protruding, mouths gnawing ahead. Biology has determined our fate as forward-oriented creatures and given us a great fear of that which lies outside our perception.

Because the total field of human vision—everything we can see along a horizontal axis— is approximately 200 degrees, much of our environment goes by undetected. Half the world is always out of view. Like a car without mirrors, you have a massive, permanent blind spot. Turn in any direction, and the blind spot shifts with you.

Now, this may sound painfully obvious to you. Of course we can’t see everything. No, there’s not a monster behind me. But, if you let your imagination wander, you might consider the netherworld lurking just over your shoulder.

Horror films certainly have. The wiki site TV Tropes, a goldmine of pop-culture analysis, includes an entry called “Enemy Rising Behind,” dedicated to a particular type of camera shot. It reads:

“Bob is facing the camera. Unknown to him, an enemy is rising up behind him. It may be a giant monster whose head is rising up to his level, an enemy in an aircraft, or a much smaller enemy rising up right behind Bob. The important details are that Bob has no idea of the danger coming, and that the shot is continuously from in front of Bob until he has some inkling of the danger.”

Watching enemies rise behind in the Alien, Jaws, or Jurassic Park movies, we want to shout at the screen: “Look, behind you!” But it’s usually too late. A character’s been gobbled up, and he never saw it coming. This is the danger of the blind spot at its most basic: death from behind. Stay aware, or get eaten yourself, as predator becomes prey.

There’s a great episode of Doctor Who that explores the dread of the unseen from another, Lovecraftian angle. In “Turn Left,” Donna, the Doctor’s time-travelling companion, is assailed by a Time Beetle. This alien creature attaches itself to Donna’s back, sucking away her time energy and creating a parallel universe in which she never meets the Doctor. Mainly, the Time Beetle is a plot device.

It’s also extremely unnerving. Throughout the episode, Donna’s friends catch momentary glimpses of the Time Beetle, which seems to shift between universes. “There’s something on your back,” they tell her. But whenever Donna looks, it disappears. The Time Beetle becomes a part of her, an unconscious beast that manipulates from the darkness. Donna is plagued by the sense that some hidden force is corrupting her life.

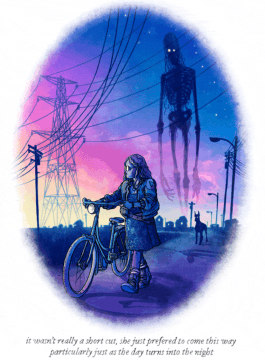

Brian Coldrick, a web artist, has created a webcomic called “Behind You” that often plays on the same idea. In his words, “Each page is simply a character with someone, or something, behind them and one line of text. While some of them touch on well worn horror tropes, none are direct adaptations of existing stories.” The images are fantastic, each one telling a contained story and invoking the uncertain terror of being watched.

This uncanny feeling is familiar to scopophobes. Scopophobia is the fear of being seen or stared at. Freud called scopophobia the “dread of the evil eye” and associated it with the ego’s never-ending project of self-criticism. You are afraid to be seen because some part of you feels ashamed. Cameras, windows, and mirrors become malevolent objects to the scopophobic. For some, the worst possibility of all is being gazed upon without knowing it, as in Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, a circular prison that allows a single watchman to monitor all prisoners without them knowing if they’re being watched at any given moment.

Critical theorists have written at length (at times, incomprehensibly) about the powerful influence of the Other and the strange force of the Gaze. In short, human beings are startled by the fact that we are not only producers of subjective experience—constantly dreaming the world into existence—but also visible objects ourselves. The sensation of being seen unsettles our experience of ourselves, driving a wedge between our mental existence and our physical being. The evil eye reminds us that we are material: for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.

In the meantime, you keep a vigilant watch for the stranger who stares at you, who stands too close, who follows you down the street.

I once had a strange experience walking home from work. It was late at night, and I was alone on an empty avenue. I suddenly had a strong feeling that someone was behind me, no more than a few feet away. I turned around with bated breath.

But, of course, no one was there.