by Akim Reinhardt

Every Democrat, and many independent voters, breathed an enormous sigh of relief when Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump in the November election. Now they are all nervously counting down the days (16) until the last of Trump’s frivolous lawsuits is dismissed, his minions’ stones bounce of the machinery of our electoral system, and Trump is finally evicted from the White House. Only then can we set about repairing the very significant damage that Trump and Trumpism have wrought upon our republican (small r) and democratic (small d) institutions.

Every Democrat, and many independent voters, breathed an enormous sigh of relief when Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump in the November election. Now they are all nervously counting down the days (16) until the last of Trump’s frivolous lawsuits is dismissed, his minions’ stones bounce of the machinery of our electoral system, and Trump is finally evicted from the White House. Only then can we set about repairing the very significant damage that Trump and Trumpism have wrought upon our republican (small r) and democratic (small d) institutions.

Yet at the same time, many savvy Democrats do not want Trump to actually go away. Remain out of office, whether president or dog catcher? Absolutely. But quietly fade into the woodwork as former presidents generally do, and no longer be a presence in American politics? Well, not exactly.

Why? Because here in the waning days of Trump’s presidency, Republicans face a potential crisis. Like a piece of hot iron on an anvil, the party is being bent in two different directions, hammered by a simple question: What comes next?

The answer is no simple matter because Trumpism was not politics as usual for America, and especially for Republicans.

Unlike Republican presidential nominees before him, Donald Trump did not ascended to the top of the GOP by building alliances with party power brokers. Instead of playing nice with them, he actually alienated them. They opposed him, and won despite them by pulling an end around and appealing directly to primary voters. He built up his cult of personality by channeling an excitable brand of right wing populism that partly eschewed Republican orthodoxy.

Trump was perhaps uniquely positioned to do this successfully. Read more »

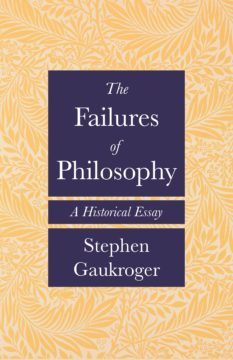

Three times have we started doing philosophy, and three times has the enterprise come to a somewhat embarrassing end, being supplanted by other activities while failing anyway to deliver whatever goods it had promised. Each of those three times corresponds to a part of Stephen Gaukroger’s recent book The Failures of Philosophy, which I will be discussing here. In each of these three times, philosophy’s program was different: in Antiquity, it tied itself to the pursuit of the good life; after its revival in the European middle ages it obtained a status as the guardian of a fundamental science in the form of metaphysics; and when this metaphysical project disintegrated, it reinvented itself as the author of a meta-scientific theory of everything, eventually latching on to science in a last attempt at relevance.

Three times have we started doing philosophy, and three times has the enterprise come to a somewhat embarrassing end, being supplanted by other activities while failing anyway to deliver whatever goods it had promised. Each of those three times corresponds to a part of Stephen Gaukroger’s recent book The Failures of Philosophy, which I will be discussing here. In each of these three times, philosophy’s program was different: in Antiquity, it tied itself to the pursuit of the good life; after its revival in the European middle ages it obtained a status as the guardian of a fundamental science in the form of metaphysics; and when this metaphysical project disintegrated, it reinvented itself as the author of a meta-scientific theory of everything, eventually latching on to science in a last attempt at relevance.

For the past few years, I’ve been taking a fairly deep dive into attempting to understand the physical and ecological changes occurring on our planet and how these will affect human lives and civilization. As I’ve immersed myself in the science and the massive societal hurdles that stand in the way of an adequate response, I’m becoming aware that this exercise is changing me, too. I feel it inside my body, like a grey mass coalescing in my chest, sticking to everything, tugging against my heart and occluding my lungs. A couple of months ago, I decided to stop writing on this subject, to step away from these thoughts and concerns, because of their discomfiting darkness.

For the past few years, I’ve been taking a fairly deep dive into attempting to understand the physical and ecological changes occurring on our planet and how these will affect human lives and civilization. As I’ve immersed myself in the science and the massive societal hurdles that stand in the way of an adequate response, I’m becoming aware that this exercise is changing me, too. I feel it inside my body, like a grey mass coalescing in my chest, sticking to everything, tugging against my heart and occluding my lungs. A couple of months ago, I decided to stop writing on this subject, to step away from these thoughts and concerns, because of their discomfiting darkness.

If one enters the name “Ellen Page” into the search box at

If one enters the name “Ellen Page” into the search box at  Arma virusque cano: Sing,

Arma virusque cano: Sing, This Christmas, I stayed in a Marriott in the town where my kids live. Like most people, my business and personal travel has mostly ground to a halt in the last 9 months. So I was pleasantly surprised by the check-in experience the hotel provided me to allow for social distancing. I’m a long-time Marriot member and have their app on my phone. Using it, I was able to check-in ahead of time, and when my room was ready, they sent me a mobile key.

This Christmas, I stayed in a Marriott in the town where my kids live. Like most people, my business and personal travel has mostly ground to a halt in the last 9 months. So I was pleasantly surprised by the check-in experience the hotel provided me to allow for social distancing. I’m a long-time Marriot member and have their app on my phone. Using it, I was able to check-in ahead of time, and when my room was ready, they sent me a mobile key.  In the early months of 1966, whenever a familiar look of boredom settled in my mother’s eyes at the thought of cooking, I’d suggest, “Why don’t we go out for pizza?”

In the early months of 1966, whenever a familiar look of boredom settled in my mother’s eyes at the thought of cooking, I’d suggest, “Why don’t we go out for pizza?”

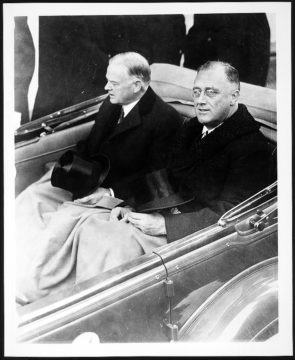

Adlai Stevenson, in the concession speech he gave after being thoroughly routed by Ike in the 1952 Election, referenced a possibly apocryphal quote by Abraham Lincoln: “He felt like a little boy who had stubbed his toe in the dark. He said that he was too old to cry, but it hurt too much to laugh.”

Adlai Stevenson, in the concession speech he gave after being thoroughly routed by Ike in the 1952 Election, referenced a possibly apocryphal quote by Abraham Lincoln: “He felt like a little boy who had stubbed his toe in the dark. He said that he was too old to cry, but it hurt too much to laugh.”