by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

“Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your hair, so that I may climb the golden stair:” the witch sings to the blonde Rapunzel imprisoned in her tower.

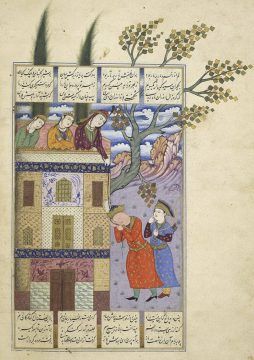

In a legend, Rudabeh, the dark-haired princess of Kabul lets her hair down like a rope for prince Zal to climb up to her tower. She has eyes “like the narcissus and lashes that draw their blackness from the raven’s wing.” Her name is Rudabeh, “child of the river.”

Rapunzel is Brothers Grimms’ nineteenth century retelling of Persinette (1689), which is surmised to be an adaptation of the millennia old Persian legend of Rudabeh, famously recast in Shahnameh, the Persian masterpiece written by the poet Ferdowsi in the eleventh century. Ferdowsi’s lofty praise in his poem set a high bar for the artists who painted the legendary beauty Rudabeh: “about her silvern shoulders two musky black tresses curl, encircling them with their ends as though they were links in a chain.”

The links between such stories from the East and the West emerged first through startling common etymologies in everyday language, songs and stories. As a child tuned in to the world of words, I asked for stories when my mother combed my hair, and caught images and contours of sound in fairy tales in English, the text running from the left to the right and stories of the Alif Laila (One Thousand and One Nights) and Qissa Chahaar Darvish (The Story of the Four Dervishes) in Urdu from the right to left.

Double-sided access to the lexical spectrum of the Indo-European as well as Abrahamic civilizations, was the beginning of a lifelong curiosity about the historical crossovers leading to how I experienced the world at any given time, illuminated more and more from learning about the history of the ancient trade routes known as the “Silk Road,” along and across which goods and ideas have been exchanged, languages have been shaped and legends shared for thousands of years.

The routes were so named (by a German scholar as recently as in 1877) because silk was the earliest commodity known to be traded westwards; in the various civilizations that have been part of this network, and in various hubs of it, however, these routes have been recalled by whatever material, mythic, ideational or mystic association significant to their time and place.

Peshawar, the city of my childhood, was once an outpost of the Silk Road. As one of the oldest, continuous cities of South Asia whose recorded history goes back at least 539 BCE, it appears in ancient Zoroastrian, Buddhist, Hindu, Chinese and Greek texts, as a place significant to their respective histories; a famous geopolitical threshold, the city was an entry point for a slew of outsiders, among them Alexander the Great and Babur, the founder of the Mughal dynasty. In more recent times, Peshawar has been a capital of Sikh and Afghan dynasties and has been under British rule.

Empire and the struggle against it, is part of Peshawar’s mythos; as a child I saw the city eclipsed by the ravages of the Soviet war across the border in Afghanistan and later, as a grownup, the American-led war and its present, ongoing repercussions.

While conquerors continue to write history as they always have, the truer histories come from the brush between cultures when ordinary people interact, trade and talk as individuals. One of the places in Peshawar that held the most fascination for me as a child was the Qissa khwani bazaar (or “market of the storytellers”), one of great relics of the Silk Road era where traders would gather in tea shops and swap stories.

Years have passed since my last visit to Qissa khwani bazaar, which I remember only vaguely, but I do have a vivid recollection of the pied teapots and small ceramic “kehwa” cups I caught sight of (in the windows of tea shops) conjuring the old times when traders staying in caravanserais would drink tea here, enrapt in each other’s stories; the fact that these stories linked the cultural imagination of places as diverse as China, India, Central Asia, Levant, North Africa and Europe, is something that still feeds my sense of wonder. Sadly, there is no combing of hair and telling of stories in my house but my children are growing up in a world dominated by another bustling network and thoroughfare where disparate cultures meet and stories are born: the internet.