by Thomas Larson

It’s Monday, 1:45, and six men and I sit in a circle with our German-trained psychotherapist, an imperious woman who reminds us that she is here to help only if we get bogged down or offer guidance and that we men need to find our own way through our turmoil, which is the point of the group and the point of each of us paying $3000 per year. I’m fairly new, so before I speak, I’m seeking some level of comfort or commonality among us, and every week I come up short. I’m not yet adjusted and unsure what I should be adjusting to.

It’s Monday, 1:45, and six men and I sit in a circle with our German-trained psychotherapist, an imperious woman who reminds us that she is here to help only if we get bogged down or offer guidance and that we men need to find our own way through our turmoil, which is the point of the group and the point of each of us paying $3000 per year. I’m fairly new, so before I speak, I’m seeking some level of comfort or commonality among us, and every week I come up short. I’m not yet adjusted and unsure what I should be adjusting to.

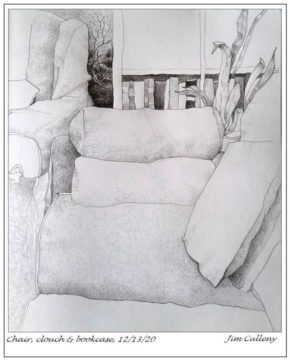

Obviously, I don’t know these men. And I doubt I’d associate with them outside this forum or be in a social situation where we’d meet. Case in point, the tanned man (our real names cannot be shared). The tanned man has the time-clocked sadness my father had at fifty-five, the greying hair above his ears, the loyalty to a global corporation and the ease of leveraged investments about him, a man who regards his goldenness as some golf-cart anhedonia, with his deck shoes, and his velour pullover, and his browning legs and white ankles and baggy, bluish shorts, and his marriage run aground, whose chassis has been scraping the gravel for a couple years now.

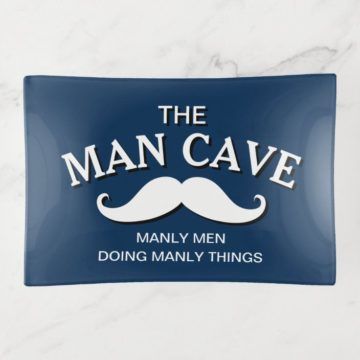

He says everything he’s tried won’t move the needle, that is, between him and his wife. The strangely placid woe he wears into our sessions I find disturbing; he always sits in the room’s lone hard back chair, best, he says, for his sofa-ruined back, telling us, as he did last Monday, that he’s still sleeping on the leather couch in the basement where she sentenced him (hard-on in tow, an adolescent bit of humor) and where nailed above the foot of the stairs a little plaque reads, I’m not kidding, “Man Cave.”

His tortured spine is no better, he says, even after a beach-walk and the treadmill, and yet he seems relaxed becoming, I presume, accustomed to us commiserating with his fraught condition, we his brethren therapists, though there’s wariness and worry in how often his legs cross and uncross as if this is a job interview: Why do I notice all this? Why can’t I concentrate on my own shit? I’ve got plenty of it, guy-wired in me and my partner, a problem with medications. Read more »

We are entering the aftermath. Two of the most epic and wrenching struggles in American history are finally playing out to their conclusions. At last we see a conclusive democratic rejection of a presidency built on systematic lying and racism. At the same time we look just weeks or months ahead for vaccines that will liberate us from our deadly yearlong pandemic.

We are entering the aftermath. Two of the most epic and wrenching struggles in American history are finally playing out to their conclusions. At last we see a conclusive democratic rejection of a presidency built on systematic lying and racism. At the same time we look just weeks or months ahead for vaccines that will liberate us from our deadly yearlong pandemic. A Task for the Left

A Task for the Left

The first time I ever left home without leaving home I was twelve years old, recently back from a winter trip to Mexico. Routinely sent to bed at 8 pm (my parents were old and old-fashioned), always wondering how to fill the inevitable two hours of insomnia, I opted to return to Mexico, not as the sleepless chiquita that I was, but as the fierce guerilla chief I would become in the narrative, leading a band of outlaw Aztecs in raids against a host of injustices from base camp in a desert. No precedents existed for my leadership skills in real life, but within the carefully sculpted storyline of the daydream, I was both charismatic and respected, not merely proficient but also inspired, a warrior queen to rival any Amazon.

The first time I ever left home without leaving home I was twelve years old, recently back from a winter trip to Mexico. Routinely sent to bed at 8 pm (my parents were old and old-fashioned), always wondering how to fill the inevitable two hours of insomnia, I opted to return to Mexico, not as the sleepless chiquita that I was, but as the fierce guerilla chief I would become in the narrative, leading a band of outlaw Aztecs in raids against a host of injustices from base camp in a desert. No precedents existed for my leadership skills in real life, but within the carefully sculpted storyline of the daydream, I was both charismatic and respected, not merely proficient but also inspired, a warrior queen to rival any Amazon. In the summer of 2000, after completing my bachelor’s degree in engineering, I had to decide where to go next. I could either take up a job offer at a motorcycle manufacturing plant in south India, or I could, like many of my college friends, head to a university in the United States. Most of my friends had assistantships and tuition waivers. I had been admitted to a couple of state universities but did not have any financial support. Out a feeling that if I stayed back in India, I’d be ‘left behind’ – whatever that meant: it was only a trick of the mind, left unexamined – I took a risk, and decided to try graduate school at Arizona State University. I hoped that funding would work out somehow.

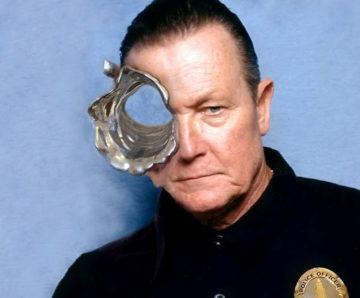

In the summer of 2000, after completing my bachelor’s degree in engineering, I had to decide where to go next. I could either take up a job offer at a motorcycle manufacturing plant in south India, or I could, like many of my college friends, head to a university in the United States. Most of my friends had assistantships and tuition waivers. I had been admitted to a couple of state universities but did not have any financial support. Out a feeling that if I stayed back in India, I’d be ‘left behind’ – whatever that meant: it was only a trick of the mind, left unexamined – I took a risk, and decided to try graduate school at Arizona State University. I hoped that funding would work out somehow. One of the most interesting and memorable characters in sci-fi films is the

One of the most interesting and memorable characters in sci-fi films is the

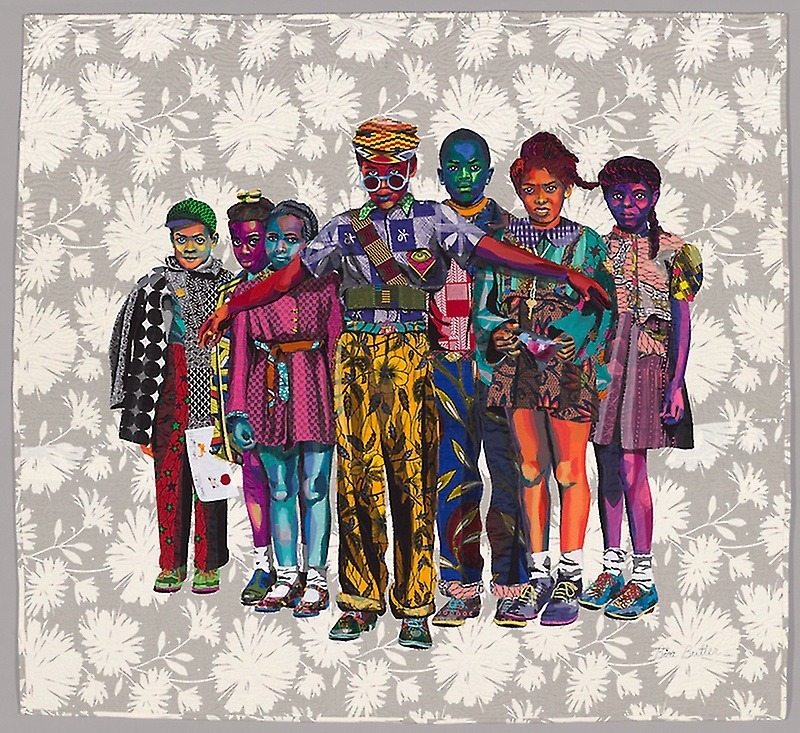

Bisa Butler. The Safety Patrol. 2018.

Bisa Butler. The Safety Patrol. 2018.

On 9 October 1990, President George H.W. Bush held a news conference about Iraqi-occupied Kuwait as the US was building an international coalition to liberate the emirate. He said: “I am very much concerned, not just about the physical dismantling but about some of the tales of brutality. It’s just unbelievable, some of the things. I mean, people on a dialysis machine cut off; babies heaved out of incubators and the incubators sent to Baghdad … It’s sickening.”

On 9 October 1990, President George H.W. Bush held a news conference about Iraqi-occupied Kuwait as the US was building an international coalition to liberate the emirate. He said: “I am very much concerned, not just about the physical dismantling but about some of the tales of brutality. It’s just unbelievable, some of the things. I mean, people on a dialysis machine cut off; babies heaved out of incubators and the incubators sent to Baghdad … It’s sickening.”