Photo taken two days ago of the main church in the town of Welschnofen in the Eggental valley of the South Tyrol.

A Voyage to Vancouver, Part Three

by Eric Miller

Flat cap

For my part, the plank staircase angling by rickety twitches cliff-side down to Wreck Beach reminds me of the steps that stagger toward the Whirlpool below Niagara Falls. Each increment here in British Columbia is too short—each increment there, on the frontier of Ontario, too long. Yet a kind of music accompanies treading down both, we play them like a keyboard, the music of inhibition and the music of extension.

I cannot for the longest time glimpse saltwater. Can you see it? I perceive cedars and arbutus, and observe the adjacent protean precipitousness of tumbling rills, ruffled like fern leaves, rippling like otters. These waters don’t have to flex their knees. Every time we think it’s over the creaking flight continues! I have the time to think of Ontario, and to think of how the British conceived of the Niagara River as a part of the Saint Lawrence, and to think of characters I have conceived, members of the British party going upstream to administer the new province of Upper Canada, the year being 1792. Now, like Dante in La Vita Nuova, let me provide a context for the cameo with which I hope to entertain you as, lurching ourselves a little woodenly, imitating thus the boards of hundreds of discrete steps that support our resolve, we bring ourselves, with luck, onto the sea-level reach of Wreck Beach. There is something prosodic and stirring about staircases is there not? They are symbols of so much! To descend a staircase is not necessarily an anticlimax is it?—in spite of etymology. Read more »

Film Review: “Bliss” Isn’t

by Alexander C. Kafka

The disappointing new film Bliss is maddening in ways both intended and surely unintended. A heady rumination on the nature of reality featuring two bright stars in quirky character roles was an attractive proposition, but it doesn’t pan out.

The disappointing new film Bliss is maddening in ways both intended and surely unintended. A heady rumination on the nature of reality featuring two bright stars in quirky character roles was an attractive proposition, but it doesn’t pan out.

The film sometimes conveys a real sense of dissociation. The script could have been honed with that goal in mind and become a workable study of two drug-addled down-and-outs, Greg and Isabel (Owen Wilson and Selma Hayek), living in a tent city on the streets of L.A.

Alternatively, Bliss could have been a pure sci-fi reverie as we learn that the couple’s gritty misadventures are actually a computer-simulated role-playing game devised in another L.A. of affluence, comfort, and ease. In lounges, players access the virtual reality through tubes up their noses connected to large tanks with floating brains. Take that, Xbox! This provocatively reverses the premise of the Matrix franchise, in that rather than being slaves to technological overlords, humanity has been freed by its own digital prowess, revisiting a synthesized street life only as a reminder of the pollution, poverty, and mayhem civilization has overcome. Read more »

Monday, February 1, 2021

Beyond Equality of Opportunity

by Martin Butler

Both morally and politically, equality is a powerful ideal. Over the last two centuries it has been one of the fundamental demands of most movements aimed at improving society. The French Revolution is the paradigm case. Despite its enduring relevance, however, equality has always been a somewhat vague ideal. It was hardly a problem for the revolutionaries in France, where the difference between the aristocracy and the sans-culottes was so stark that further elaboration was unnecessary. Over the years, however, the question ‘equality of what?’ has become more pressing, and many answers have been highlighted: equal rights, equal pay, equal treatment, equal opportunities, equality under the law, equality of outcome, to name but a few. Rather than just looking at these answers, perhaps we should start by identifying the source of the ideal of equality’s ethical power, and see where this leads us.

Both morally and politically, equality is a powerful ideal. Over the last two centuries it has been one of the fundamental demands of most movements aimed at improving society. The French Revolution is the paradigm case. Despite its enduring relevance, however, equality has always been a somewhat vague ideal. It was hardly a problem for the revolutionaries in France, where the difference between the aristocracy and the sans-culottes was so stark that further elaboration was unnecessary. Over the years, however, the question ‘equality of what?’ has become more pressing, and many answers have been highlighted: equal rights, equal pay, equal treatment, equal opportunities, equality under the law, equality of outcome, to name but a few. Rather than just looking at these answers, perhaps we should start by identifying the source of the ideal of equality’s ethical power, and see where this leads us.

It seems to me that there are at least two powerful ethical justifications, which, although overlapping lead in somewhat different directions. The problem is that one of these has tended to dominate over the other. One source arises from an obvious principle of rationality. It is clearly irrational to treat people differently for irrelevant reasons. Parentage, accent, race, age, wealth, gender, social class, sexual orientation, religious belief, physical attractiveness, etc. are in most cases completely irrelevant to a person’s capacity to play a particular role in society. In the past, privilege, tradition and prejudice have been the main reasons why irrelevant factors have been treated as relevant in the selection of individuals for particular roles, especially those associated with power and prestige. Only with the enlightenment did the irrationality of this tendency begin to be felt, and ever since, there has been slow but steady progress towards disregarding it. Of course, it is rational not to treat people equally with regards to factors that are relevant to that role. We have no problem in discriminating when it comes to giving some people and not others jobs on the basis of their ability to perform those jobs, or giving some people and not others a place on a course of study based on their capacity benefit from that course. But there must be equality of opportunity to be considered for those roles. The irrelevances listed above should not interfere with the process of getting to the starting blocks, even if it is clear that not everyone can win the race.

This compelling narrative of ‘equal opportunities’ has become the pre-eminent expression of the ideal of equality in modern liberal democracies, a conception of basic fairness which is about removing barriers and creating a level playing field. In recent years this has led to a focus on policies that attempt to create this level playing field. This powerful ethical argument is supported by pragmatic considerations. Nobody wants a doctor chosen from a limited pool of candidates. Equal opportunities allow us to get the right people onto the starting blocks so that the one who wins is more likely to be the fastest, rather than the fastest from a skewed and therefore limited selection. Equal opportunities is both fair recruitment and smart recruitment.

However, the story starts to get more complicated if we pursue this ideal further still. Read more »

Views Of Future Earth

by Usha Alexander

[This is the eighth in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

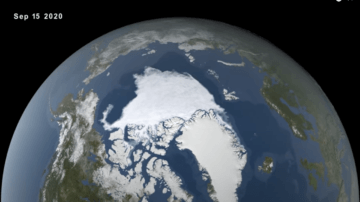

In the late fifteenth century, European seafarers began searching for what they called the “Northwest Passage,” a fabled route across the Arctic Ocean, which would allow them to sail northward from Europe directly into the Pacific in search of fortune. But the Arctic of their time, during the so-called Little Ice Age of the fourteenth to mid-nineteenth centuries, was covered by thick, impenetrable sheets of ice and densely packed icebergs. Nor had they any reasonable expectation that the great mass of ice would soon melt away. That they imagined finding a reliably navigable route through a polar sea seems to me a case of wishful thinking, a folly upon which scores of lives and fortunes were staked and lost, as so many adventurers attempted crossings, only to flounder and often die upon the ice.

In the late fifteenth century, European seafarers began searching for what they called the “Northwest Passage,” a fabled route across the Arctic Ocean, which would allow them to sail northward from Europe directly into the Pacific in search of fortune. But the Arctic of their time, during the so-called Little Ice Age of the fourteenth to mid-nineteenth centuries, was covered by thick, impenetrable sheets of ice and densely packed icebergs. Nor had they any reasonable expectation that the great mass of ice would soon melt away. That they imagined finding a reliably navigable route through a polar sea seems to me a case of wishful thinking, a folly upon which scores of lives and fortunes were staked and lost, as so many adventurers attempted crossings, only to flounder and often die upon the ice.

But now that the Arctic sea ice is melting away, the Northwest Passage has become real in a way the adventurers of old could not have dreamed. Today, nations encircling the Arctic Ocean jockey for control of its waters and territorial rights to newly exposed northern continental shelves, which promise to be full of oil and gas. What had been a deadly fantasy is now a luxury cruise destination flaunting an experience of rare wonder, including opportunities to watch polar bears on the hunt. “A journey north of the Arctic Circle is incomplete without observing these powerful beasts in the wild,” entices the Silversea cruises website, with nary a note about the bears’ existence being threatened by the very disintegration of their icy habitat that makes this wondrous cruise possible. Meanwhile, in China, the emergent northern sea routes have been dubbed the Polar Silk Road, projecting a powerful symbol of their past wealth and influence onto an unprecedented reality.

By now, we’re all aware that the planet is profoundly changing around us: angrier weather, retreating glaciers, flaming forests, bleaching coral reefs, starving polar bears, disappearing bees. Yet how blithely we go on making plans, as though the future will follow as neatly and predictably from today, as today did from yesterday. From buying a new beachside home to booking a cabin in the redwoods a year in advance, the ongoing planetary changes apparently figure little in the plans so many people make. It seems I regularly read articles in which mainstream economists make predictions that entirely disregard the changing climate and collapsing biodiversity, as though these concerns lie beyond our economies. Even governments and corporations who seek to profit from changes like the opening of the Arctic Ocean often presume themselves the drivers of “disruption,” creating new market opportunities in an otherwise stable or predictable world. They don’t seem to recognize that the true nature of what’s upon us might just be greater than they imagine and far more consequential. Read more »

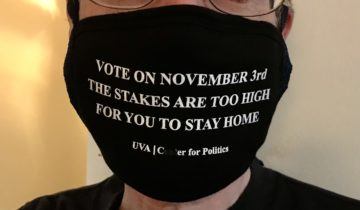

The Third Transition: Trump to Biden and the Return of Politics

by Michael Liss

Some may belittle politics, but we know, who are engaged in it, that it is where people stand tall. And although I know it has its many harsh contentions, it is still the arena that sets the heart beating a little faster. And if it is on occasions the place of low skullduggery, it is more often the place for the pursuit of noble causes, and I wish everyone, friend or foe, well, and that is that, the end. —Tony Blair, ending his last PMQ, June 27, 2007

Yes, that was Tony Blair, the man everyone loves to hate, but in those few short words, he managed to capture the highs and lows of a democratic system. Politics can be rough and tawdry, but debates can be substantive, goals high, and accomplishments, perhaps not as high, but still advancing the good of the many. In the end, you fight like cats and dogs, but you shake hands, accept the verdict, and prepare yourself for the next battle.

This belief, that there is always next time, is predicated on three key assumptions—that, in our system, there is, in fact, always a next time, that even winning coalitions will screw up enough to ensure that the next time may be viable, and that the loser (if the incumbent) will cooperate in the orderly transition of power.

That is the theory, and, for most of our history, that has also been the reality. Winning coalitions stay winning because they deliver policies that a majority support. They fray when internal discipline breaks down (usually because of unsatisfied desires or ambitions), and/or when they become so sclerotic, doctrinaire, or just wrong that enough of the public rejects them. Lincoln’s election in 1860 reflected a reality that the disparate needs of North and South could no longer be reconciled within the status quo. FDR’s trouncing of Hoover was the rational judgment of the voters that Hoover had simply failed, and would continue to fail. Trump’s victory in 2016 was a reminder of not only Hillary Clinton’s flaws as a candidate, but also Barack Obama’s shortcomings as a President. As much as I admired Obama, he didn’t do enough for enough people to earn transferable loyalty during a time when, as my friend Bill Benzon notes, the tectonic plates were moving. The voters really do choose. Read more »

Perceptions

Kosovo at 13

by Rafaël Newman

In the summer of 1977 my father invited me to tea at the Hotel Grande Bretagne in Athens. I had turned 13 that spring, and instead of a bar mitzvah, prohibited by matrilineal descent and an antipathy to organized religion, my father and I were en route to Israel, to visit the kibbutz where he had worked in the mid-1950s. We had flown from Vancouver to Amsterdam, proceeded by train to Rome, and continued by rail across Italy to Brindisi, by ferry to Patras, and by coach to Athens. From there we would eventually embark, at Piraeus, on the crossing to Haifa; for the moment we were enjoying some sightseeing in the Greek capital.

In the summer of 1977 my father invited me to tea at the Hotel Grande Bretagne in Athens. I had turned 13 that spring, and instead of a bar mitzvah, prohibited by matrilineal descent and an antipathy to organized religion, my father and I were en route to Israel, to visit the kibbutz where he had worked in the mid-1950s. We had flown from Vancouver to Amsterdam, proceeded by train to Rome, and continued by rail across Italy to Brindisi, by ferry to Patras, and by coach to Athens. From there we would eventually embark, at Piraeus, on the crossing to Haifa; for the moment we were enjoying some sightseeing in the Greek capital.

We were by now already several days into a three-week trip and I was slowly adjusting to the oddness of being alone with my father in unfamiliar territory. At our first stop the exciting absurdity of the canals in Amsterdam had made up somewhat for nine hours of jetlag; my New World teenage composure, however, was tested by the shared bathroom on the corridor of our Dutch hotel. It was the first of several jarring encounters. On the train bound south from Holland we were interrogated at the German border by a customs guard, who had entered our sleeping compartment and, at the sight of a youth with an older man, their journey having originated in Amsterdam, had me roll up my sleeve so he could check for tracks. Later, in the dormitory of the youth hostel in Rome in which my father’s salary as an assistant professor had billeted us, I awoke in my bunkbed to see a fellow guest naked in the middle of the room, gingerly applying salve to his posterior. Read more »

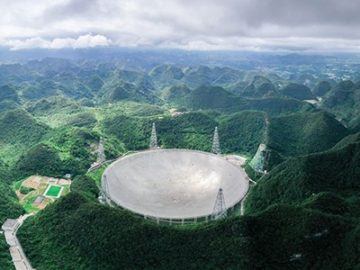

To Arecibo

by R. Passov

I had hand-written a simple essay: My father is in prison, my mother works, welfare helps and I got a 1310 on my SATs. The letter of acceptance from UCLA was short – we’re happy to let you know….

The hill leading to the main quad of the UCLA campus is terraced into three landings by flat, wide brick stairs built in the late 1920’s, depression-era stimulus. By the time I got there, Bel Air, Beverly Hills, and Westwood surrounded that hill.

An old Daily Bruin lay on the ground. Past the comings and goings of Bruin Life, blond and blue, basketball, tennis and good teeth, I found a classified ad: Wanted, cook for a professor’s family, free room and board, walking distance to campus.

I can cook, I thought. Walking distance was a plus. I found a payphone, heard age in the voice that answered along with an English that came from afar and was invited to interview.

I found the house a few blocks into the hills above Sunset Blvd. Dr. Mommarts was tall, slender, newly old, easy. His white-blond hair fell uncombed. His soft brown eyes, protected by wild eyebrows. He spoke with an accent, in proper English, yet his words lacked edge, one ending after the next began.

He assumed I would not have responded to the ad without having knowledge of cooking. I got a brief tour of a modern one-story home anchored by a single hallway whose wall was a long stretch of glass, rimming a flat yard. “Here’s the kitchen,” he said. There were two rooms, one with a sink, counter space, stove, oven. And a second with cabinets, a second sink and a wide wooden table. “And the preparation room.”

From the kitchen we walked down the hallway, past the end of the windows, to a small room with a single bed and a dresser, located near to a bathroom. “Here’s where you’ll stay,” he said and that was it. I was a cook. Read more »

Some Songs from a Fallen Empire

by Philip Graham

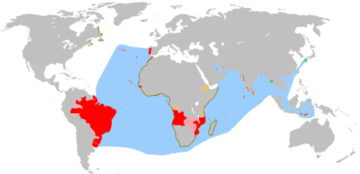

I’ve long been partial to Portuguese culture, so when Portugal transferred its last colonial holding, Macau, back to Chinese rule in 1999 , a friend surprised me with his marveling reaction: “Portugal had an empire? Who knew?”

I’ve long been partial to Portuguese culture, so when Portugal transferred its last colonial holding, Macau, back to Chinese rule in 1999 , a friend surprised me with his marveling reaction: “Portugal had an empire? Who knew?”

Perhaps his reaction shouldn’t have surprised me. In the United States, steeped as we are in the history of the United Kingdom’s “empire on which the sun never sets,” few are aware that the Portuguese accomplished the first European globe-spanning empire, beginning in the 15th century.

When I lived in Lisbon for a year, I noticed that my Portuguese friends wrestled with the legacy of their country’s history. They felt pride at the achievements of their intrepid ancestors’ global reach. But they also felt shame, because while all empires break too much before they reshape the chaos they created, Portugal’s empire was especially bad.

The Portuguese initiated the transatlantic slave trade in 1444, which has bedeviled and tormented much of the world ever since. Sixty years later, the Viceroy Alfonso Albuquerque expanded Portuguese power not only as exploration for economic reasons, but as a brutal crusade against Islam. By 1580, the empire extended from Brazil to Africa, from India to Malaysia and on to the Indonesian island of Timor.

The Portuguese initiated the transatlantic slave trade in 1444, which has bedeviled and tormented much of the world ever since. Sixty years later, the Viceroy Alfonso Albuquerque expanded Portuguese power not only as exploration for economic reasons, but as a brutal crusade against Islam. By 1580, the empire extended from Brazil to Africa, from India to Malaysia and on to the Indonesian island of Timor.

So what happened to this Portuguese empire, which now no longer exists? Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

The Bigger Lie

by Eric J. Weiner

There is never time in the future in which we will work out our salvation. The challenge is in the moment; the time is always now. —James Baldwin

Before the pomp and circumstance of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris’s inauguration officially framed the white supremacist insurrection at the Capitol on January 6 an outlier of U.S. history, an affront to American Exceptionalism, and a brief pause in the Nation’s moral progress, there was a lot of talk about the “big lie” that precipitated it. I expect, with the impeachment trial scheduled to begin next week, that we will again hear quite a bit about the “big lie” and its power to change water into wine. Historically, the big lie, lobbed in concert with many smaller lies, is the one that tips the scale of reason, fuels delusional thinking, and provides the foundation for all kinds of violence and hate. Hitler knew it when he perpetuated the big lie about Jews running a global cabal. And Trump knew it when he repeatedly told the big lie about a rigged and stolen election. Timothy Snyder, the Levin Professor of History at Yale University and author of On Tyranny (2017) says, “There are lies that, if you believe in them, rearrange everything…a big lie is a lie which is big enough that it tears the fabric of reality.” When enough people believe in the big lie, and their beliefs have time to ferment and spread, the big lie becomes a spectacle.

“The spectacle,” as Guy Deborg explained, “is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images… It is a world vision which has become objectified.” Right-wing corporate media and social media platforms, during the past five years, have helped to construct and disseminate the spectacle of the big lie, turning facts into a matter of perspective and words/images into weapons of mass delusion. From the ashes of “the real” arise the rational irrationality of relativistic thinking. The Trumpist cult of mass delusion, aided and abetted by corporate and social media, is unified by the spectacle of the big lie while becoming an integral part of it. But however dangerous the spectacle of the big lie is to democracy, it is not the most pernicious and dangerous lie in America. In fact, Trump’s big lie could not have become the spectacle it did had a bigger lie not preceded it. Read more »

White America Needs to Clean House

by Akim Reinhardt

White Americans get a lot of things wrong about race. And not just the relatively small number of blatant white supremacists, or the many millions (mostly over 50, conservative, and/or Republican) bitter about the supposedly undue attention, sympathy, and “breaks” that minorities receive; who insist actual racism was a problem only in the past, because Civil Rights “fixed” it; who believe anyone complaining about racism is just looking for an unfair edge in America’s level, color-blind playing field; who decry so-called “reverse racism”; who actually believe it is harder to be white in America than to be black or brown; or who simply minimize and downplay the existence racism.

White Americans get a lot of things wrong about race. And not just the relatively small number of blatant white supremacists, or the many millions (mostly over 50, conservative, and/or Republican) bitter about the supposedly undue attention, sympathy, and “breaks” that minorities receive; who insist actual racism was a problem only in the past, because Civil Rights “fixed” it; who believe anyone complaining about racism is just looking for an unfair edge in America’s level, color-blind playing field; who decry so-called “reverse racism”; who actually believe it is harder to be white in America than to be black or brown; or who simply minimize and downplay the existence racism.

Not just them. Even the small majority of whites who recognize that race remains a big problem in America often get it wrong. For example, many (most?) of them think that race is primarily about black and brown people. It’s not. Racism is primarily about white people.

Minorities suffer the effects of racism, and we must acknowledge and work to end that; however, you cannot cure an infection by simply placing a band-aid over the sore. You must clean out the wound thoroughly, surgically if need be, disinfect it, and then attack the infection at its root with antibiotics. In the old days it might have meant cutting off an appendage or limb. Similarly, racism won’t end or even be substantially reduced by strictly focusing on the suffering of its victims and making amends. Those are important and necessary first steps, but they don’t get at the core of the problem. Minority suffering is racism’s result, but racism is caused by what white people think and do.

White people empathizing with black and brown people is important, and it is vitally important that whites listen to minority voices. However, ending or substantially reducing racism will not come about until white people talk to each other and sort themselves out. Because racism is a white problem. Read more »

Waiting for the Messiah: Derrida and the Philosophy of Hospitality

by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

The sound of thousands of clattering stainless steel plates and bowls ripple across the water, as hundreds line up to enter the Golden Temple in Amritsar. Built atop a platform in the middle of a pool of water, this is the holiest shrine of the Sikh religion. Pilgrims arrive at the floating “Abode of God” walking slowly across a very crowded covered-causeway.

Just when you think nothing can be done to repair the world, you stand in awe as thousands are fed in the great communal kitchens of the temple.

The numbers are staggering. An army of volunteers show up every morning to chop vegetables, peel garlic, and fry roti. This in preparation for feeding tens of thousands every day. Known as the Langar, this communal meal is an act of charity and love, open and free to all. And what’s more, you don’t have to travel all the way to Amritsar to experience a Langar, as it is practiced in all Sikh places of worship around the world. Sitting on the ground shoulder-to-shoulder so that all are equal, pilgrims are provided with sustenance, ensuring that none leave the temple hungry.

Anyone is welcome to eat and anyone is welcome to serve.

In her beautiful book, Be My Guest: Reflections on Food, Community, and the Meaning of Generosity, Priya Basil—who herself hails from a Sikh family—feels it is a shame the meaning of the word “hospitality” in English has come to be so firmly associated with the industry of hospitality, something which has conflated acts of generosity with capitalist entertainment. And she rightly asks:

“What does this say about us when a notion that long implied giving without getting any return becomes synonymous with paying for services that promise customer satisfaction or your money back?” Read more »

Monday Photo

On the Road: Sri Lanka Part Two

by Bill Murray

Politics as the family business works out better for some than for others. Last year Turkish President Erdogan had to fire his son-in-law Finance Minister. And the Trumps, well … you know. But things are working out pretty well for the Rajapaksas of Sri Lanka.

The President is Gotabaya Rajapaksa, nickname “the terminator.” The Prime Minister is Mahinda Rajapaksa, his older brother. Basil Rajapaksa, “Mr. Ten Percent,” their younger brother, is a former MP. Their other brother Chamal, a former speaker of Parliament, is a cabinet minister, and Namal Rajapaksa, Mahindra’s son, is an MP and Minister of Sports, representing the next Rajapaksa generation.

When we left our story (Read part 1 here) it was six o’clock in the morning, election day 1999 in Nuwara Eliya, a highland tea-picking town south of Kandy, Sri Lanka. Two loudspeakers played the call to prayer, mounted atop a glass-enclosed Buddha statue just by the traffic circle. The sun hadn’t cleared the hills but it was set to be a glorious morning, birds and dew run riot.

At this hour, Nuwara Eliya served mostly as a regional bus station. People queued for rides and a few stores pushed open their doors. At a milk bar (that’s a name for convenience stores, here to New Zealand) I bought toothpaste and remarked how it would be a nice day. Dazzling smile: “It is election day, sir!” Read more »

Tectonic Tremors, Ghost Dancing, and the Certification Riots

Elizabeth from Knoxville

We haven’t yet settled on a name for the event. I do see “1/6” being used here and there, a formation parallel to “9/11.” However reference to 9/11 is common, well understood, and routine, while the use “1/6” is sporadic. But then the bombing of the World Trade Center is almost two decades old while the certification riots happened only yesterday. We’ve not had time to understand and assimilate them.

We don’t even know what to call them. I just used the word “riot”, but is that what they were? What does that word imply? What about “protest”, “insurrection”, “putsch”, or as Elizabeth from Knoxville said (see the video clip above), “revolution”? One might answer, “semantics, mere semantics, we all know what you’re referring to.” Well, yes, we’ve got the reference. But figuring out just what those events were, that’s not a matter of mere semantics. The legal and institutional implications of those words are quite different. Riots happen all the time, as do protests, insurrection is quite different, no?

Nor do we know just what happened. We’ve seen the videos, we recognize some of the people – how could we forget the Q-Shaman, with his skins, buffalo horns, and face paint? – and we know that five people died. But all those people and events have connections. How far do those connections reach? Who planned to storm the Capitol ahead of time with specific objectives in view and who just went along with the flow? Who talked with whom? Do any of those communication chains reach into Congress or the White House? What did Donald Trump know and when did he know it? What did he intend?

We have a nation divided against itself. Read more »

2020 in review, Silver Lining Edition, part 2

by Dave Maier

Not long ago, a reader complained, politely but firmly, about your humble author’s regrettable tendency to post something called “Blah blah blah pt. 1” and then never get back to it for part two, in particular the post about history, wondering if possibly I thought no one would notice that I had left it hanging. I admit the fault, but I assure my patient reader, or possibly readers, that I do indeed intend to finish each and every one of my multipart posts, and even to make clear how they are related to each other. (That’s the intent, anyway.) So fear not! (I do have to read some more history though … !) This time, though, I finish a different sort of multipart post: my end-of-2020 podcast. Plenty of unfamiliar names, even to me, but some great stuff! As always, widget and/or link below. Read more »

Not long ago, a reader complained, politely but firmly, about your humble author’s regrettable tendency to post something called “Blah blah blah pt. 1” and then never get back to it for part two, in particular the post about history, wondering if possibly I thought no one would notice that I had left it hanging. I admit the fault, but I assure my patient reader, or possibly readers, that I do indeed intend to finish each and every one of my multipart posts, and even to make clear how they are related to each other. (That’s the intent, anyway.) So fear not! (I do have to read some more history though … !) This time, though, I finish a different sort of multipart post: my end-of-2020 podcast. Plenty of unfamiliar names, even to me, but some great stuff! As always, widget and/or link below. Read more »

Monday, January 25, 2021

Do you have a right to own a microwave oven?

by Tim Sommers

Do you have a right to own a microwave oven? To be clear, ideally in a free society, absent a clear showing of harm to others, there’s a presumption that you can do whatever you want and own whatever you can make or buy. So, you do have a basic right to own things – to acquire property, as political philosophers like to say. But it’s consistent with that right for there to be a lot of rules and regulations around what you can own – and even prohibitions on owning certain kinds of things.

Do you have a right to own a microwave oven? To be clear, ideally in a free society, absent a clear showing of harm to others, there’s a presumption that you can do whatever you want and own whatever you can make or buy. So, you do have a basic right to own things – to acquire property, as political philosophers like to say. But it’s consistent with that right for there to be a lot of rules and regulations around what you can own – and even prohibitions on owning certain kinds of things.

Microwave ovens are complicated physical objects, tools or machines, that require pretty advanced technology and technical know-how to make and that almost no one can make all on their own. It would be odd to think of a microwave as the sort of thing you could have a right to. Before they were invented did people have a fundamental, but unexercisable right to own them? They also contain dangerous chemicals and heavy metals and are not entirely safe to discard or recycle. If new information revealed them to be even less safe than we think now, or if changing standards raised the safety bar on all appliances, microwaves could be banned. It’s hard to picture anyone arguing that microwaves couldn’t be banned because we have a fundamental right to own them.

What about cars? They kill a lot of people. But in many places, they are essential, or nearly essential, to mobility and mobility is essential to equality of fair opportunity – and some part of mobility should probably even be counted as a fundamental liberty. Still, we don’t have a fundamental right to own or drive a car – must less an unregulated, unlicensed right to own or drive one. Microwave ovens and cars and guns are just metaphysically the wrong kinds of things to be the object of basic rights, liberties, or political freedoms.

Let’s talk about guns. Read more »

Deep Disagreement and the QAnon Conspiracy Theory

by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

Deep disagreements are disagreements where two sides agree on so little that there are no shared resources for reasoned resolution. In some cases, argument itself is impossible. The fewer shared facts or means for identifying them, the deeper the disagreement.

Some hold that many disagreements are deep in this way. They contend that reasoned argument has very little role to play in discussions of the things that divide us. Call these the deep disagreement pessimists – they claim that many of the disputes we face cannot be addressed by shared reasoning.

There are also deep disagreement optimists. Their view is that deep disagreements are intractable only for contingent reasons – perhaps we have not yet surveyed all the available evidence, or we are waiting on new evidence, or there is some background shared methodological principle yet to be uncovered. With deep disagreement, the optimist holds, it is hasty to give up on rational exchange, because something useful is likely available, and the costs of passing such rational resolution up are too high. Better to keep the critical conversation going.

Disputes among pessimists and optimists regularly turn on the practical question: Are there actual deep disagreements? The debates over abortion and affirmative action were initially taken to be exemplary of disagreements that are, indeed, deep. Later, secularist and theists outlooks on the norms of life were taken to instantiate a divide of the requisite depth. More recently, conspiracy theories have been posed as points of view at deep odds with mainstream thought.

This brings us to QAnon. Read more »