by Shawn Crawford

Preachers at our Baptist church had to ask for an Amen. We weren’t just going to spontaneously let one loose. God can’t drive a parked car, my youth minister would say. Meaning you had to exert your own will as well in the pursuit of a righteous life. When it came to the Holy Spirit, we rarely even tried the ignition.

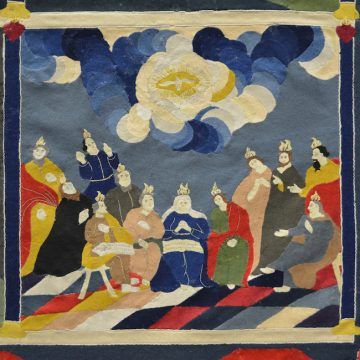

After the death of Christ, the apostles found themselves a pretty sorry lot. Scared and convinced they were the next candidates for execution, most went into hiding. What transformed them was not merely the appearance of the resurrected Jesus, but the gift of the Holy Spirit, and this gift came to them through the sound of a rushing wind and tongues of fire that descended from heaven and “came to rest on each of them” (Acts 2.3). The depiction of this event generally involves little candle flames hovering over the Apostles. As if that wasn’t cool enough, the first thing that happened for the Apostles was the ability to speak in languages they had never known. Which came in handy, because it just so happened Jews all over the world had gathered in Jerusalem for Pentecost, a derivation of a Greek word that means “fifty” and denoted the fiftieth day after Passover and the beginning of the next Jewish holiday Shavuot. Peter gave the first sermon on the need for repentance and baptism, the Christian church began, and the word Pentecost became associated with the Holy Spirit and speaking in tongues, which would eventually spawn a focus on such practices in Pentecostal churches.

* * *

Like most awesome occurrences in the Book of Acts, those things happened then but they probably weren’t happening to you. But they could. But don’t get your hopes up. That explains in a nutshell the ambivalence Baptists felt about the Book of Acts. One the one hand, they were forever going on about how they leapfrogged all the corruption and mistakes of the Catholic Church by returning to the “true” church of Acts, while at the same time having to become sophisticated defense lawyers to explain away all the parts that made them uncomfortable. Tongues had to be contained, but even more so the disturbing economic policies of the early church. The Apostles and their friends were not bastions of capitalist thought. In fact, Comrade, all that “sharing of everything they had” just wasn’t going to do. We weren’t living on a collective outside Minsk. Thank God.

The way out of all these predicaments and uncomfortable demands of the New Testament usually boiled down to this: It didn’t matter whether you shared all your possessions, or loved your enemies, or gave solace to the poor; it was your willingness to do so if asked. “Why certainly I would sell everything in a second and give it to shiftless homeless people, but I’ve just never felt God calling me to do that.” This convenient attitude allowed you to feel justified and good about your faith while simultaneously doing nothing to demonstrate your beliefs.

The strange thing is, the communal living and sharing of resources feels like the most authentic part of Acts. The natural response to a messiah that taught respect and preference for the marginalized would be to behave in just that way. Yet that part of the message always agitated and worried our church the most. Don’t let me create the impression I was some heroic voice in the wilderness, full of sacrifice. I might give condescending lectures to my parents and have hand-wringing discussions with my youth group, but I enjoyed my comfortable house and new clothes and general abundance just fine thank you very much. I thought my superiority resided not in my willingness to give away what I had, but rather in my guilt for not doing so. At the time it seemed like an immensely important distinction.

My grandmother attended the Church of Christ, and they dealt with these issues by simply declaring the Book of Acts a special, limited, one-time offer. The days of miracles and tongues and Jesus blinding you on the road to Damascus or anywhere else had ended. Now you just hunkered down and behaved yourself and hoped for the best. The Church of Christ didn’t allow musical instruments in their services because Jesus and the disciples didn’t have them. But apparently they had carpet and electricity and pews and hymnals. I admire the fact my grandmother held all these contradictions in check while being one of the kindest and most gracious people I ever knew. Then again I was her favorite; she told me so once. All the other grandchildren will have to get over it.

* * *

So speaking in tongues began as a practical gift of communication, but soon grew into an esoteric spiritual practice. People in the early Church began declaring they spoke in “heavenly tongues” that only the angels and God could understand. In a very short time, church services began producing quite a din, with people claiming their tongue more enlightened and closer to true divine utterance. Paul finally gets fed up with all the noise and declares in I Corinthians that unless some can interpret what is being said (another gift of the Spirit), people should just keep their tongues to themselves: “I would rather speak five intelligible words to instruct others than ten thousand words in a tongue” (I Corinthians 14.19). Apparently Paul was the first Baptist.

My favorite Christian Urban Legend, and there is a whole subgenre in existence, tells the story of someone rising to speak in one of these heavenly tongues. Apparently the person had been doing so for quite some time, impressing the congregation with their spiritual depth. One Sunday however a visiting missionary happened to be in attendance. As the tongue-speaker rambled on, the missionary arose shaken and afraid. “Brothers and sisters,” he declared, “this person is speaking in the language of the tribe I work with, and he is blaspheming God!” Not spiritual enlightenment, but rather demonic possession had been taking place. I could only imagine the smug satisfaction of the other church members; that’s what happened when you tried to get all uppity and act superior in your faith. Because there’s no way Mr. Tongues wasn’t lording it over everyone else.

This cautionary tale encapsulated our church’s general attitude toward the Holy Spirit in all things. We gravitated to verses like “the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, will teach you all things and will remind you of everything I have said to you” (John 14.26). The Holy Spirit operated like a nostalgic high school friend: “Remember when Jesus told the parable of the Good Samaritan? That was awesome. Good times. Good times.” And just like your friend, sometimes you remembered things a little differently or grew tired of the constant reminders of the glory days.

Until college, I never had a huge exposure to the more ecstatic forms of the Spirit. Now and then at a national spiritual conference, a contingent of people during a prayer would raise their arms in the air and sway, repeating phrases, “Yes. Thank you Jesus. Thank you.” Someone would utter what I assumed was tongues. This produced less awe and more stifled giggles than anything from me. Cynicism didn’t drive me; I wanted that experience, that feeling of abandonment before the holy. But it always felt contrived for me, a closed door my temperament and fear could never open. What was I missing?

Nothing according to the esteemed elders at my church. People that always harped on the Spirit had a whiff of hippie culture attached to them. Not unlike the Christian coffeehouse we visited in the late 70s and early 80s, featuring bands with hair down to their collars, wearing tinted glasses and playing a sanitized version of Zeppelin guitar-hero rock. My favorite song: “Don’t Get Caught in Carnalville (Don’t you get caught!)”. Great hook, sordid imagery in the name of producing chaste believers. The winning evangelical entertainment formula.

If the Holy Spirit gave you remarkable insights to share at your Bible study that was one thing, but finding yourself subject to a state of uncontrolled ecstasy was quite another. Not to mention that every terrifying act of defiance or heroism in both the Old and New Testaments was usually proceeded by the Champion of Faith being “lead by the Spirit.” This suspect member of the Trinity seemed bent on your peril or incarceration. And supposedly you ended up enjoying it all. In the Book of Acts, Paul and Silas find themselves set upon by a mob and taken to the local authorities:

The crowd joined in the attack against Paul and Silas, and the magistrates ordered them to be stripped and beaten with rods.

After they had been severely flogged, they were thrown into prison, and the jailer was commanded to guard them carefully. When he received these orders, he put them in the inner cell and fastened their feet in the stocks. (Acts 16.22-24)

There’s a lovely ending to that story, because the jailer and his household get saved, but let’s not forget the saga begins with stripping, rods, and severe flogging. Paul and Silas celebrate with a little jailhouse concert, and when offered escape through a divine earthquake, return so the jailer won’t get in trouble. Acts constantly reminds us that no one was more full of the Spirit than Paul. Other than his spectacular conversion on the road to Damascus, we preferred the later, letter-writing Paul. The one wading into petty church disputes and telling women to be submissive and quiet. Less flogging and more bureaucracy; that was our motto.

I knew nothing of the concept of Exceptionalism growing up, but the idea that our relationship with God was a little more special, a little more unique, a little more superior, permeated everything in my church. God the Father would judge others but not us; God the son could save humanity but he had saved us; God the spirit would comfort us and bring us peace as promised (John 14) but had no intention of leading us into floggable situations.

This worldview provided great solace and the sense I would be exempt from the normal suffering and trials others experienced. The end of the world could commence at any moment and would prove harrowing, but that was in the hands of a God who had everything under control. Only later would Baptists and evangelicals begin to wonder if the world was a just a bit more evil that than our God(s) was good. We might need to step in and stem the tide politically or hasten the process to ignite the Apocalypse.