Pati Hill. A Swan: An Opera in Nine Chapters, 1978 (detail from chapter 5).

by Tamuira Reid

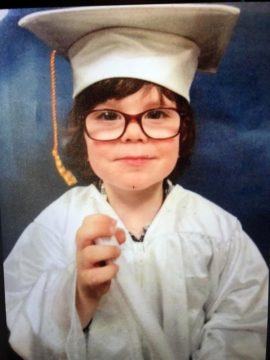

This is my son, Ollie.

This photo was taken five years ago. It’s one of my all-time favorites because of the look of absolute pride on his face. Hard-earned pride. I realize that pre-k graduation isn’t the most celebrated of milestones for a lot of families, but for us it was huge; Ollie was about to go mainstream.

Looking back at that little boy, and reflecting on the kid he is now, I feel lucky that we live in a city like New York. A city that has endless resources, creativity, spirit, hustle. The city that has taught us what it means to be humble, be grateful. A city that has afforded my disabled son access to an equal and appropriate education, and a public school with teachers who have loved and unconditionally supported him. A city that knows how to rally.

This is my son, Ollie.

Currently a proud in-coming fourth-grader, but with the same coke-bottle glasses and wide, generous smile. His backpack is usually absent-mindedly left open, and is stuffed with graphic novels, half-eaten bags of flaming hot Cheetos, a stress ball, and various contraband (slime, hotwheels cars, Skittles to share on the bus with potential friends, Pokemon cards to trade although he hasn’t figured out exactly how). As he passes you during drop-off, he will greet you with a “Good morning!”, maintaining direct eye contact, something that still feels, at times, unnatural to him.

Ollie Duffy doesn’t really walk from point A to point B, because the “electricity” running through his body, as he’d tell you, is hard to control. His movements are a little bit “more slippery” and unpredictable, like a sideways skip/grapevine type of thing, until he inevitably trips over his own feet. And even though he knows where he’s supposed to go, he often forgets mid-journey.

If Ollie sees your child crying, he will try to comfort them. Usually with a hug, sometimes with a Skittle. If that doesn’t work, he’ll sit nearby so they don’t feel alone. If Ollie is in class with a bully, he’ll feel sorry for them because being angry can mean you’re just frustrated, and he knows how that feels.

This is my son, Ollie.

Heart as big as the planet. Read more »

by Emrys Westacott

A friend, knowing that I’ve been learning German, recently sent me a volume of Theodore Fontane’s poetry. Fontane (1819-1898) is best known today for the novels that he wrote in the later part of his life. But some his poems have an affecting simplicity–a simplicity that is perhaps especially charming to those of us who are less than fluent in German. Here is one lyric that particularly caught my attention. It expresses a sentiment that seems most suitable to the present time as we approach the end of a bleak winter and, one hopes, of a devastating pandemic. Naturally, the translation takes some liberties in an attempt to retain something of the feel and spirit of the original.

A friend, knowing that I’ve been learning German, recently sent me a volume of Theodore Fontane’s poetry. Fontane (1819-1898) is best known today for the novels that he wrote in the later part of his life. But some his poems have an affecting simplicity–a simplicity that is perhaps especially charming to those of us who are less than fluent in German. Here is one lyric that particularly caught my attention. It expresses a sentiment that seems most suitable to the present time as we approach the end of a bleak winter and, one hopes, of a devastating pandemic. Naturally, the translation takes some liberties in an attempt to retain something of the feel and spirit of the original.

Trost Consolation

Tröste dich, die Stunden eilen, Be comforted, the hours fly,

Und was all dich drücken mag, Like everything that’s sad and grey,

Auch das Schlimmste kann nicht weilen, Even the worst will pass on by,

Und es kommt ein andrer Tag. And there’ll come another day.

In dem ew’gen Kommen, Schwinden, In life’s eternal rising, falling,

Wie der Schmerz liegt auch das Glück, Happiness lies alongside pain,

Und auch heitre Bilder finden And, like the sunlight, brighter scenes

Ihren Weg zu dir zurück. Will find their way to you again

Harre, hoffe. Nicht vergebens Be patient, hopeful. It may help

Zählest du der Stunden schlag, To count the striking hours away.

Wechsel ist das Los des Lebens, One’s lot in life is always changing,

Und – es kommt ein andrer Tag. And – there’ll come another day.

by Godfrey Onime

I am reminded of an observation made by an African comedian at a wedding reception I once attended in Atlanta. He quipped that the English language tends to identify even the most hideous diseases by the most beautiful names. Names so lyrical, so poetic, so sensuous you almost wish to contract the disease. He rattled off some examples: Hepatitis. Cholecystitis. Syphilis. Cancer. “How beautiful!” he exclaimed.

The jokester contrasted this proclivity with some gruesome names Africans assign to even the most benign conditions, such as with the Yorubas of Nigeria — Lapalapa (for dermatitis); or jedijedi (for diarrhea). The comedian may romanticize the English names for diseases, but not so with most of my patients. Especially not so with the middle-aged woman whom I diagnosed with syphilis a few years back. “You mean my nose could fall off?” seemed to be her biggest fear, explaining that she once heard that syphilis could destroy the “snout,” as she put it.

I scrutinized the woman, taking in her straight nose and high cheekbones. Giggling, I said, “Maybe you get to go back in time and join the ‘No Nose Club’. Perhaps you could find out who Mr. Crumpton really was.”

“Mr. who?”

###

Beautiful or not, it turns out that the origin of the name for syphilis, ironically, came from a poem, written by Girolamo Fracastoro, an Italian physician, scholar and poet. The poem, Syphilis sive morbus gallicus (translated to Syphilis or The French Disease), tells the story of a shepherd boy named Syphilis who angered the Greek god Apollo and was given the disease bearing his name as punishment. Although the affliction was more colloquially called “The Pox,” the term syphilis stuck as the proper name. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Eric Miller

Discovery

Conditions on the ground, if you want the moral of a garden or this excursion right away, are widely discrepant from what they look like from afar. In this respect, naturalists concur with soldiers.

Linnaeus’s Philosophia Botanica, a manual for those with some interest in plant life, tells the eighteenth-century traveller to attend to everything, etiam tritissima, even the tritest, the most well worn, entirely commonplace things. Nowadays we use the word “non-descript” when we want to avoid talking about what is so boring there are no words for it but that adjective. Yet in Linnaeus’s day “non-descript” meant something no one had ever said a word about, in a particular way—a naturalist’s way. Times change but a botanical garden is about philosophy still, it is about discovery don’t you think? Discovery, collection, not to say exclusion are obvious topics once we consent to enter the precincts. How does discovery differ from inventing? Who discovered what? How we discover is naturally a dimension of what we discover. That revelation goes on. We discover meanwhile what we can, there is much we cannot, such is our constitution. Or we discover it, and we forget it. I could not even recount this experience had I not already substantially forgotten it. Obliviousness is the prerequisite of any chronicle. So welcome to Van Dusen Gardens, Vancouver.

Rules for visitors

Do you hear that, too? Could I be right? Yes, it is the voice of a daemon—the Genius of the Place. What could this Spirit be saying? Read more »

by Jackson Arn

They marched us to a room with yellow walls

and tables painted pink, like our uniforms

so we could sit and disappear. We wandered

by tiles and corners, carrying the stink

of desperation. A chair caught me,

because it thought I needed something old

to steady me, and it had the canniness

to offer me a book I used to read

before I got lost. Everything had changed

except the picture on page four, a trout

about to feed a mad king in a bath.

We’d stayed the same size: fish soon to be food,

globe-eyed babyish unthinking gusto,

and me, reading myself back to the flood.

by Dwight Furrow

For many wine lovers, understanding wine is hard work. We study maps of wine regions and their climates, learn about grape varietals and their characteristics, and delve into various techniques for making wine, trying to understand their influence on the final product. Then we learn a complex but arcane vocabulary for describing what we’re tasting and go to the trouble of decanting, choosing the right glass, and organizing a tasting procedure, all before getting down to the business of tasting. This business of tasting is also difficult. We sip, swish, and spit trying to extract every nuance of the wine and then puzzle over the whys and wherefores, all while comparing what we drink to other similar wines. Some of us even take copious notes to help us remember, for future reference, what this tasting experience was like.

For many wine lovers, understanding wine is hard work. We study maps of wine regions and their climates, learn about grape varietals and their characteristics, and delve into various techniques for making wine, trying to understand their influence on the final product. Then we learn a complex but arcane vocabulary for describing what we’re tasting and go to the trouble of decanting, choosing the right glass, and organizing a tasting procedure, all before getting down to the business of tasting. This business of tasting is also difficult. We sip, swish, and spit trying to extract every nuance of the wine and then puzzle over the whys and wherefores, all while comparing what we drink to other similar wines. Some of us even take copious notes to help us remember, for future reference, what this tasting experience was like.

In the meantime, we argue with each other on Twitter fighting over whether a wine is terroir-driven or a technological abomination, typical or atypical, over-oaked or under ripe. We scour Wine Spectator‘s Annual Top 100 looking for who’s up and who’s down and complain about inflated wine scores and overblown wine language.

In other words, we really seem to care about getting it right, identifying a wine’s essence and properly locating it in the wine firmament. We want our judgments to conform to the actual properties of a wine and its relations. Read more »

At the deserted millennium-old abbey at Neustift in the South Tyrol a couple of days ago.

by Alexander C. Kafka

Covid has killed two and a half million people worldwide. A conspiracy-embracing, white-supremacist, fascist cohort of Americans are represented by opportunistic enablers in Congress. Texas diverts attention from its fatal mishandling of a winter storm by prematurely and irresponsibly declaring the end of the pandemic. And after a year, we’re all mostly still isolated at home — that is those fortunate enough to have a home in the wake of financial chaos.

Covid has killed two and a half million people worldwide. A conspiracy-embracing, white-supremacist, fascist cohort of Americans are represented by opportunistic enablers in Congress. Texas diverts attention from its fatal mishandling of a winter storm by prematurely and irresponsibly declaring the end of the pandemic. And after a year, we’re all mostly still isolated at home — that is those fortunate enough to have a home in the wake of financial chaos.

I don’t know about you, but I could use a laugh.

Thus I was looking forward, beyond all measure, to the sequel to Coming to America (1988), that whimsical, goofy, good-hearted John Landis-helmed star vehicle for Eddie Murphy in his prime.

Its successor, Coming 2 America, is, alas, a forced, lavishly produced clunker that tries to make up in guest stars what it lacks in purpose. Directed by Craig Brewer, it has a few chuckles, eye-popping costumes by Ruth E. Carter, some moments of nostalgic glow around its multi-generational cast, and a reprise of amusing prosthetic-job character bits for Murphy and Arsenio Hall. But it mostly wastes its stars’ talents in an overworked and uninspired script. Read more »

by Dave Maier

One problem plaguing contemporary anti-Cartesians (pragmatists, Wittgensteinians, hermeneutic philosophers, etc.) is that it can seem that we are competing against each other, trying to do better than everyone else what we all want to do: get past the dualisms and other infelicities of the modern picture while at the same time absorbing its lessons and retaining its good aspects. We waste our time fighting each other instead of our common enemy. Why is it so hard to see ourselves as all on the same team?

One problem plaguing contemporary anti-Cartesians (pragmatists, Wittgensteinians, hermeneutic philosophers, etc.) is that it can seem that we are competing against each other, trying to do better than everyone else what we all want to do: get past the dualisms and other infelicities of the modern picture while at the same time absorbing its lessons and retaining its good aspects. We waste our time fighting each other instead of our common enemy. Why is it so hard to see ourselves as all on the same team?

One reason is that when push comes to shove, or even before that, we simply follow traditional philosophical practice by providing arguments to show that we are right and they are wrong, thus construing the differences among our views as constituting differences in belief rather than, for example, the practical differences between different tools or perspectives. It is as if we have internalized the traditional criticisms: that we have abandoned objective truth and the objective world it represents in favor of our own subjective purposes. No, we say, watch us talk among ourselves! We care about truth just as much as you! Phenomenology is false and pragmatism is true, as my fully rigorous and entirely professional argument shows! Assent is required, on pain of irrationality!

Even when we’re not fighting among ourselves in this way, that same metaphilosophical ideal can still cause trouble. For instance, I have chosen to present my particular brand of anti-Cartesianism as a characteristically pragmatist philosophy. Naturally I draw inspiration and/or ideas from philosophers who do not identify as pragmatists (after all, we all reject the Cartesian mirror of nature). But in practice this can lead to some discomfort. If while pushing a pragmatist line I help myself to a Wittgensteinian (or Davidsonian or Nietzschean) insight, the question will naturally arise: what entitles me to enlist these people in my cause? Am I saying Wittgenstein or Davidson was a pragmatist? What should I make of the differences between these very different philosophers? Read more »

by Martin Butler

For many years I taught ethics to 16-19 year olds, and was often struck not only by how strongly certain ideas resonated with the students, but how unfamiliar they were with these big ideas, the product of hundreds of years of western culture. Kant and virtue ethics in particular seemed to chime with them. It made me think that these ideas should not be restricted to the narrow group of individuals who happen to have chosen to study philosophy. They are not academic curios but immensely influential and should surely be part of any ethical education. I believe that a knowledge of virtue ethics in particular could help today’s young people navigate the complex and often frightening world that they face.

Traditionally religious education has been the arena where ethical topics are covered, usually with the focus on ethical dilemmas such as euthanasia, abortion, and the status of animals. These are important and interesting topics that need to be discussed but they don’t provide the kind of ethical framework I have in mind. The treatment of ethics at this level can often produce a kind of paralysis of neutralism, a kind of ‘some people say this and others say that – take your pick’ approach, though there are areas where a more assertive line is taken.

No one denies, for example, that we really do have certain rights, this is beyond opinion. In the UK recently there has also been a push to include in the curriculum what are described as ‘British values’ (I have never been quite sure why they are distinctly British.) These comprise the rule of law, tolerance, democracy, and individual liberty. Other values such as equality, respect, diversity, inclusivity are also often given prominence. All of this is important but not enough. It is quite impersonal and abstract and hardly helpful to someone seeking a more direct guide on how their lives might be led. These ethical ideas are also quite static. You either accept them or you don’t, and there is no developmental dimension that could connect with someone wanting to improve their life both ethically and psychologically. Religious belief can give this more personal kind of guidance but there should surely be something that fills this role for those who are not religious. Read more »

by Ruchira Paul

Travelers to India came from all corners of the world through the ages for different reasons. The very first modern humans probably came there in order to escape harsh climate conditions elsewhere in the world. Latter day visitors arrived with varied objectives in mind. Some came seeking material fortune, some for spiritual enlightenment and others merely out of curiosity. A few who came, took what they wanted and left. Others came to conquer and decided to stay and make India their home. Then there were mercenary visitors who looked at India as a vast revenues source for enriching themselves and their own native lands while also seeing an opportunity to instill their religious and “civilizing” values on a foreign nation. They too decided to stay but never thought of India as home. India still attracts visitors from across the world. Most come as tourists to check out its numerous and varied natural and historical vistas (there is always the Taj Mahal). Some may be enticed by more quirky and personal adventures such as chasing the monsoon or seeking the ever elusive spiritual and emotional fulfillment. Scholarly pursuits and business opportunities attract others to the second most populous nation in the world which defines itself as a multi-cultural modern day free market democracy with an ancient checkered past that is a palimpsest of layers upon layers of human foot print left by visitors who crisscrossed its landscape in all directions for many thousands of years.

Travelers to India came from all corners of the world through the ages for different reasons. The very first modern humans probably came there in order to escape harsh climate conditions elsewhere in the world. Latter day visitors arrived with varied objectives in mind. Some came seeking material fortune, some for spiritual enlightenment and others merely out of curiosity. A few who came, took what they wanted and left. Others came to conquer and decided to stay and make India their home. Then there were mercenary visitors who looked at India as a vast revenues source for enriching themselves and their own native lands while also seeing an opportunity to instill their religious and “civilizing” values on a foreign nation. They too decided to stay but never thought of India as home. India still attracts visitors from across the world. Most come as tourists to check out its numerous and varied natural and historical vistas (there is always the Taj Mahal). Some may be enticed by more quirky and personal adventures such as chasing the monsoon or seeking the ever elusive spiritual and emotional fulfillment. Scholarly pursuits and business opportunities attract others to the second most populous nation in the world which defines itself as a multi-cultural modern day free market democracy with an ancient checkered past that is a palimpsest of layers upon layers of human foot print left by visitors who crisscrossed its landscape in all directions for many thousands of years.

The author of “Indians…” Namit Arora is a visitor in his own land. Born and educated in India, Arora left for foreign shores to pursue higher education and later a career as an engineer in Silicon Valley. After two decades of living abroad, in 2013 he returned to India to settle there permanently. This book is the record of his travels through India to the same places first in 2006 and a return visit in 2019. The author speaks both as an insider familiar with India as also an outsider who can examine the country of his birth through the lens of a global perspective. Arora is an enthusiastic and informed world traveler and photographer who periodically took time off from work to visit many far corners of the world. Read more »

a story,

a recollection

of 79 summer solstices

bundled in one thought

of when I was young—a carpenter

with muscles, sweating,

lugging planks from lumber stacks

to half-framed houses, stud walls

proud in sun, precise in ranks

………………………………………. a thought

that segues into a later solstice

down the line, along the way, a solstice

of love and its making, a tale

with science thrown in,

math and passion, geometry, physics—

stuff I’d read somewhere, sometime,

picked up or always known

in helical dreams, stuff that

fits and shifts, all true:

flight and gravity

Jim Culleny

5/13/19, rev:5/25/20

by Usha Alexander

[This is the ninth in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

—Change. Resilience. Where do we start? I’ve got no idea. What happens after this? Listen! The answer is here!—

—Change. Resilience. Where do we start? I’ve got no idea. What happens after this? Listen! The answer is here!—

These words, splashed on posters, jumped out at me from images sent by a friend. The posters were part of an exhibition called We Need To Talk About Fire, hosted at an artists’ gallery along the Nowra River, about halfway between Sydney and Canberra. The Nowra River region had been hard-hit by the catastrophic Australian bushfires of 2019–20, following an unprecedented drought. Fire season in Australia is worsening as the planet warms, just as it is in the western United States, the Amazon, and Siberia. And the 2019–20 Australian season was particularly horrific, igniting a follow-on spate of depression and suicides in the area. What struck me about these posters was the raw simplicity of their messages, which ranged from forceful platitudes to agonized queries.

In their talk about these bushfires of extraordinary fury, worsened by climate change, there’s no mention of technical solutions. No demand for new wind farms or lowered carbon intensity. Instead, the posters surface what so often gets buried beneath the statistics, acronyms, and cost-benefit analyses common in our dialogs on climate and environment. They voice the thoughts of people who narrowly escaped the flames as the sky burned. People who lost pieces of their lives in an incomprehensible inferno—loved ones or homes or a quietude of mind. For me, the posters recalled the millions more, elsewhere, who might also be expressing similar feelings: Survivors of entire towns leveled by fire in the western United States, from Paradise, California in 2018, to the several communities of Detroit, Blue River, Vida, Phoenix, and Talent, Oregon in 2020. Survivors of back-to-back typhoons Kenneth and Idai, the two most powerful cyclones ever to strike Mozambique, which hit within six weeks of one another, in March and April of 2019, fueled by rising sea surface temperatures. Survivors of typhoon Goni, the strongest recorded cyclone ever to make landfall anywhere, which hit the Philippines just days after typhoon Molave had hammered the same region, during the Covid-19 pandemic in October and November of 2020. Others too, for whom the damages and dangers of our rapidly changing planet must already feel immediate, existential, and relentless, eclipsing hopes for a return to “normalcy.” Read more »

by Eric J. Weiner

In 1940, at the height of Hitler’s invasion of Western Europe, Walter Benjamin, from Vichy France wrote, “The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘emergency situation’ in which we live is the rule. We must arrive at a conception of history that is in keeping with this insight.”[1] In our current historical context, his words are instructive for two reasons. First, they were written in the context of Nazi occupation with death breathing down his neck. In spite of these extreme conditions, Benjamin refused to see the emergency situation he was in as historically exceptional; his refusal to turn his back on the dialectic under these circumstances was extraordinary and, as we know now, at least in terms of ideology, prescient. Second, his theses about the concept of history, 80 years after he first conceived them, still resonate today. From the mismanaged pandemic and Trump’s fascistic incitement of a white supremacist insurrection at the Capitol to the continuing systemic assault and murder of African Americans by police, the failure of capitalism to eradicate poverty, growing economic inequality, deepening home and food insecurity, and the broken promise of public education to become the “great equalizer” of opportunity, the United States is struggling through what many people have mischaracterized as an unprecedented national crisis of existential proportions. It appears we have not learned what Benjamin suggested the tradition of the oppressed ought to have taught us: We have still not arrived at a conception of history that allows us to see the web of current crises as the rule, not the exception. Read more »

In 1940, at the height of Hitler’s invasion of Western Europe, Walter Benjamin, from Vichy France wrote, “The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘emergency situation’ in which we live is the rule. We must arrive at a conception of history that is in keeping with this insight.”[1] In our current historical context, his words are instructive for two reasons. First, they were written in the context of Nazi occupation with death breathing down his neck. In spite of these extreme conditions, Benjamin refused to see the emergency situation he was in as historically exceptional; his refusal to turn his back on the dialectic under these circumstances was extraordinary and, as we know now, at least in terms of ideology, prescient. Second, his theses about the concept of history, 80 years after he first conceived them, still resonate today. From the mismanaged pandemic and Trump’s fascistic incitement of a white supremacist insurrection at the Capitol to the continuing systemic assault and murder of African Americans by police, the failure of capitalism to eradicate poverty, growing economic inequality, deepening home and food insecurity, and the broken promise of public education to become the “great equalizer” of opportunity, the United States is struggling through what many people have mischaracterized as an unprecedented national crisis of existential proportions. It appears we have not learned what Benjamin suggested the tradition of the oppressed ought to have taught us: We have still not arrived at a conception of history that allows us to see the web of current crises as the rule, not the exception. Read more »

by Rafaël Newman

Mourning is in season. Newspapers of record these days publish interactive mass obituaries, images of “ordinary” people fallen to “the opioid crisis” or to Covid-19 (the front page of the Sunday New York Times was recently riven down the middle by a monolith composed of thousands of dots, growing denser towards the base, each representing a victim of the virus: the whole reminiscent of the graphic tributes to 9/11). The inauguration of the US president in January featured, in lieu of most spectators, ranks of flags, symbolizing the past year’s losses. The annual observation of International Holocaust Remembrance Day in Germany, held this year as for the past quarter century on January 27 at the Reichstag in Berlin, featured a remarkable ceremony marrying reconciliation with the starkest grief. In his latest book, the memoir-cum-poetics Inside Story, Martin Amis eschews his characteristic charades in a sincere and extended eulogy for Saul Bellow, Philip Larkin, and Christopher Hitchens, three of the central figures in the author’s professional and affective life. And, 15 years after it first appeared, The Year of Magical Thinking, Joan Didion’s essay on death and bereavement, persists on various bestseller lists.

Mourning is in season. Newspapers of record these days publish interactive mass obituaries, images of “ordinary” people fallen to “the opioid crisis” or to Covid-19 (the front page of the Sunday New York Times was recently riven down the middle by a monolith composed of thousands of dots, growing denser towards the base, each representing a victim of the virus: the whole reminiscent of the graphic tributes to 9/11). The inauguration of the US president in January featured, in lieu of most spectators, ranks of flags, symbolizing the past year’s losses. The annual observation of International Holocaust Remembrance Day in Germany, held this year as for the past quarter century on January 27 at the Reichstag in Berlin, featured a remarkable ceremony marrying reconciliation with the starkest grief. In his latest book, the memoir-cum-poetics Inside Story, Martin Amis eschews his characteristic charades in a sincere and extended eulogy for Saul Bellow, Philip Larkin, and Christopher Hitchens, three of the central figures in the author’s professional and affective life. And, 15 years after it first appeared, The Year of Magical Thinking, Joan Didion’s essay on death and bereavement, persists on various bestseller lists.

Public commemoration of the dead famously deploys performative language – that is, it accomplishes what it sets out to do simply by its enunciation. Thus Pericles, in Thucydides’ reconstruction of his funeral oration during the Peloponnesian War, and Lincoln, in his Gettysburg Address, perform the unity of their respective “peoples” by eulogizing battle dead; while the institution of the cenotaph, the tomb of the Unknown Soldier, is such a central feature of the performance grammar of national identity that, according to Benedict Anderson, there is no need to specify the provenance of the particular “ghostly national imaginings” with which each discrete tomb is “saturated”. The grave itself has become an eloquent “speech act”. Read more »

by Jeroen Bouterse

Unfortunately, it is always worth your time to read a book in praise of the humanities. Given the unenviable position of the humanities in public education and in contemporary cultural and (especially) political discourse about valuable expertise, any author that comes to their defense has to find a strategy to shift the narrative, and will thereby almost invariably do something interesting.

Unfortunately, it is always worth your time to read a book in praise of the humanities. Given the unenviable position of the humanities in public education and in contemporary cultural and (especially) political discourse about valuable expertise, any author that comes to their defense has to find a strategy to shift the narrative, and will thereby almost invariably do something interesting.

They move our focus from economic value to democracy and citizenship, for example. Or they argue that there is not actually a mismatch between the skills provided by a well-balanced liberal arts curriculum and the demands of technocapitalism, or that the humanities themselves produce the same kinds of intellectual goods as the natural sciences with which they tend to be contrasted.

These apologies are intellectually creative, though with luck some of them may grow to be new clichés. In their diversity, they also have something in common, which is that they project a rather straightforward view of the knowledge that the humanities and (other) sciences produce. One point on Martha Nussbaum’s agenda in Not For Profit, for instance, is to “teach real and true things about other groups”.

I feel slightly uneasy about this. Maybe this kind of book is not the place to get all difficult about the words “real and true”, but whenever elevator words like those are used with such confidence, part of me is inclined to get difficult about them – to look for the social and cultural interests that put them there, for instance. What is more, the place where I learned to ask those questions was during my history major; they seem to me to point to something that is particular about the humanities, something that gets lost in these defenses. Read more »

by Brooks Riley