by Philip Graham

Whenever I discover a band that sports an accordion in the lineup, I’m ready to listen.

Whenever I discover a band that sports an accordion in the lineup, I’m ready to listen.

But this wasn’t always so.

It all goes back to the mid-1960s, those days of my mid-adolescence, when my father’s favorite cousin, who we called our “aunt” May, came to visit nearly every weekend. The year before, her hard-drinking brother’s liver had finally given up on him, and my father wanted to draw her closer to our family. Aunt May lived alone, unmarried and childless. As if this was a condition that needed explanation, our parents whispered to us a secret we were never to repeat aloud, that she once had a boyfriend, but he’d died in World War II and she never found another man like him.

After the ritual of a Saturday afternoon dinner, the time arrived for the ritual of settling in the living room to watch the latest installment of Aunt May’s favorite program, Lawrence Welk’s musical variety show. My younger brother and I were expected to keep her company. We, too, loved our kind and self-effacing aunt, but to my easily-affronted adolescent self, Lawrence Welk had invented his show to personally torment me. It was a kind of musical quicksand, Stepford Wives music, everything that rock and roll was trying to replace or destroy. Read more »

An empty space sits where I once sat. I miss it. I miss the strangers I shared it with, and a few regulars with whom I achieved a nodding relationship. A couple of baristas I might greet and chat up. Very briefly.

An empty space sits where I once sat. I miss it. I miss the strangers I shared it with, and a few regulars with whom I achieved a nodding relationship. A couple of baristas I might greet and chat up. Very briefly.

There is a story that Clemenceau, the Prime Minister of France, was in conversation with some German representatives during the Paris peace negations in 1919 that led to the Treaty of Versailles. One of the Germans said something to the effect that in a hundred years time historians would wonder what had really been the cause of the Great War and who had been really responsible. Clemenceau, so the story goes, retorted that one thing was certain: ‘the historians will not say that Belgium invaded Germany’.

There is a story that Clemenceau, the Prime Minister of France, was in conversation with some German representatives during the Paris peace negations in 1919 that led to the Treaty of Versailles. One of the Germans said something to the effect that in a hundred years time historians would wonder what had really been the cause of the Great War and who had been really responsible. Clemenceau, so the story goes, retorted that one thing was certain: ‘the historians will not say that Belgium invaded Germany’.

We are not where we were one year ago—or have we just returned?

We are not where we were one year ago—or have we just returned? In the part of my life when I was most actively trying to invent myself as a writer, I was working as a high school teacher and was desperately unhappy. (Notice the way that I put this: “I was working as a high school teacher,” not “I was a high school teacher”; the notion that a job defines a person still disgusts me.) In the evenings, I left work and wrote magazine pitches, not as many, I realize in retrospect, as could have brought me success, but enough to keep me talkative in the teacher’s lounge. I had the impression, back then, that a writer could make a name for himself on the basis of a single strong piece, and since my work was deeply derivative—I was, after all, inexperienced—I hatched a plan.

In the part of my life when I was most actively trying to invent myself as a writer, I was working as a high school teacher and was desperately unhappy. (Notice the way that I put this: “I was working as a high school teacher,” not “I was a high school teacher”; the notion that a job defines a person still disgusts me.) In the evenings, I left work and wrote magazine pitches, not as many, I realize in retrospect, as could have brought me success, but enough to keep me talkative in the teacher’s lounge. I had the impression, back then, that a writer could make a name for himself on the basis of a single strong piece, and since my work was deeply derivative—I was, after all, inexperienced—I hatched a plan.

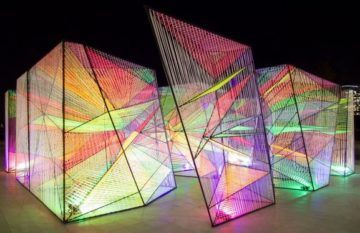

Abstract: This article, written by the Digital Philosophy Group of TU Delft is inspired by the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma. It is not a review of the show, but rather uses it as a lead to a wide-ranging philosophical piece on the ethics of digital technologies. The underlying idea is that the documentary fails to give an impression of how deep the ethical and social problems of our digital societies in the 21st century actually are; and it does not do sufficient justice to the existing approaches to rethinking digital technologies. The article is written, we hope, in an accessible and captivating style. In the first part (“the problems”), we explain some major issues with digital technologies: why massive data collection is not only a problem for privacy but also for democracy (“nothing to hide, a lot to lose”); what kind of knowledge AI produces (“what does the Big Brother really know”) and is it okay to use this knowledge in sensitive social domains (“the risks of artificial judgement”), why we cannot cultivate digital well-being individually (“with a little help from my friends”), and how digital tech may make persons less responsible and create a “digital Nuremberg”. In the second part (“The way forward”) we outline some of the existing philosophical approaches to rethinking digital technologies: design for values, comprehensive engineering, meaningful human control, new engineering education, and a global digital culture.

Abstract: This article, written by the Digital Philosophy Group of TU Delft is inspired by the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma. It is not a review of the show, but rather uses it as a lead to a wide-ranging philosophical piece on the ethics of digital technologies. The underlying idea is that the documentary fails to give an impression of how deep the ethical and social problems of our digital societies in the 21st century actually are; and it does not do sufficient justice to the existing approaches to rethinking digital technologies. The article is written, we hope, in an accessible and captivating style. In the first part (“the problems”), we explain some major issues with digital technologies: why massive data collection is not only a problem for privacy but also for democracy (“nothing to hide, a lot to lose”); what kind of knowledge AI produces (“what does the Big Brother really know”) and is it okay to use this knowledge in sensitive social domains (“the risks of artificial judgement”), why we cannot cultivate digital well-being individually (“with a little help from my friends”), and how digital tech may make persons less responsible and create a “digital Nuremberg”. In the second part (“The way forward”) we outline some of the existing philosophical approaches to rethinking digital technologies: design for values, comprehensive engineering, meaningful human control, new engineering education, and a global digital culture.

Religion has always had an uneasy relationship with money-making. A lot of religions, at least in principle, are about charity and self-improvement. Money does not directly figure in seeking either of these goals. Yet one has to contend with the stark fact that over the last 500 years or so, Europe and the United States in particular acquired wealth and enabled a rise in people’s standard of living to an extent that was unprecedented in human history. And during the same period, while religiosity in these countries varied there is no doubt, especially in Europe, that religion played a role in people’s everyday lives whose centrality would be hard to imagine today. Could the rise of religion in first Europe and then the United States somehow be connected with the rise of money and especially the free-market system that has brought not just prosperity but freedom to so many of these nations’ citizens? Benjamin Friedman who is a professor of political economy at Harvard explores this fascinating connection in his book “Religion and the Rise of Capitalism”. The book is a masterclass on understanding the improbable links between the most secular country in the world and the most economically developed one.

Religion has always had an uneasy relationship with money-making. A lot of religions, at least in principle, are about charity and self-improvement. Money does not directly figure in seeking either of these goals. Yet one has to contend with the stark fact that over the last 500 years or so, Europe and the United States in particular acquired wealth and enabled a rise in people’s standard of living to an extent that was unprecedented in human history. And during the same period, while religiosity in these countries varied there is no doubt, especially in Europe, that religion played a role in people’s everyday lives whose centrality would be hard to imagine today. Could the rise of religion in first Europe and then the United States somehow be connected with the rise of money and especially the free-market system that has brought not just prosperity but freedom to so many of these nations’ citizens? Benjamin Friedman who is a professor of political economy at Harvard explores this fascinating connection in his book “Religion and the Rise of Capitalism”. The book is a masterclass on understanding the improbable links between the most secular country in the world and the most economically developed one.

Tragically, President Biden’s 21-page “

Tragically, President Biden’s 21-page “