by Bill Murray

Thirty years ago this week two million people joined hands forming a human chain across 676 kilometers of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Known as the Baltic Way, the visually arresting stunt was a cinematic cri de coeur for freedom.

Thirty years ago this week two million people joined hands forming a human chain across 676 kilometers of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Known as the Baltic Way, the visually arresting stunt was a cinematic cri de coeur for freedom.

In time freedom was theirs. The Russian military fled, sometimes trashing their barracks and looting along the way the way. As a measure of the state in which the Soviet Union left the Baltics, still now, thirty years on it takes around seven hours to travel by train between Tallinn and Riga, the capitals of two European countries separated by scarcely 200 miles. Imagine.

The Estonian and Latvian railways have finally co-ordinated their timetables, but you still have to walk across the platform to change trains at the border. By contrast, the drive takes perhaps four and a half hours, and, as both are now Schengen countries, your vehicle breezes through the abandoned border post without slowing down.

Much of that drive, after the tidy Estonian border town of Parnu, takes you south along the coast of the Gulf of Riga. Estonia and Latvia are lovely during this early bit of Baltic autumn, grasses with full summer growth waving in fields skirting Baltic shores.

•••••

The next time you’re in Tallinn, make time to visit the well done KGB Museum atop the Viru hotel. From a perch on the hotel’s top floor, the KGB spied on guests. The lifts stop at the 22nd floor and to get to the museum you proceed through locked gates to 23, a secret lair of surreptitious surveillance so needlessly paranoid the whole display veers toward the camp.

Funny the needless paranoia. Funny what they did. Funny only in retrospect, I’m sure, and from a considerable remove.

From the Viru’s opening in June of 1972 until May of 1991 when the spies hastily abandoned their post, ripping out planted microphones in guest room phones but leaving behind other incriminating items, they would mark out a restaurant table at which to seat a suspect foreigner, more often than not some poor sod Estonian immigrant back to visit family from the west.

The table’s ashtray (photo) contained a microphone (remember, this was 1980s and everyone smoked). If the guest put the ashtray on the next table, a waiter would sweep by to put it back. Plates like the one in the photo also had microphones in false bottoms.

The table’s ashtray (photo) contained a microphone (remember, this was 1980s and everyone smoked). If the guest put the ashtray on the next table, a waiter would sweep by to put it back. Plates like the one in the photo also had microphones in false bottoms.

The KGB spied on the help, too. Top-floor apparatchiks would leave a purse (the red one in the photo) on a table once in a while, and if a worker was tempted to open it in search of hard currency they’d be dye-bombed with red dye and immediately fired. Which was problematic, because unemployment was illegal, and could land you a spell in jail if you had a troublesome past.

Officially illegal unemployment produced unlikely jobs. The Viru, one hotel, mind, sustained 1080 jobs (for which 4000 applied). A job at the Viru brought proximity to hard currency and a scent, if nothing more, of the wider world. You’ve heard the wry old East Bloc joke about how the state would pretend to pay and the workers would pretend to work. At the Viru, you could make a career as a Food Weigher. There were to be 82 grams of chicken meat in chicken Kiev and 75 grams in à la carte versions.

A planned economy had to be planned and somebody had to do it. While potatoes, flour and meat were rationed via the Trade Board of the city council, more exotic orange juice, necessary for foreign hotel guests and high-ranking apparatchiks on holiday or “educational meetings,” was ordered from Moscow.

A Viru job meant access to forbidden goods. Tickets to the variety shows staged there and Viru bakers’ cakes, both could be traded; both were good as currency. Stockmann, the Helsinki-based department store with branches in Estonia, Latvia and Russia, still sells cakes using the recipe of then-Viru chef Kuno Plaan. His cakes, tradable for, say, auto parts, were a wild favorite, with people queueing from before dawn every day. The museum claims that Plaan’s liver paté could sell 100 kilos/day.

All of the Soviet Union’s tourist hotels were operated by Intourist, which at its height handled 145 hotels all the way to Vladivostok. Guests could expect the treatment the museum at the Viru depicts, all across the land. A floor lady, a hall monitor on each floor, recorded every client’s visitors, contacts, comings and goings. These ladies were usually older on the assumption that they wouldn’t meet a tall, dark foreign stranger and flee the country.

The hotel reception collected guests’ passports. At Tallinn’s Viru most visitors, almost all of them Finns, arrived on the ferry from Helsinki in tour groups, as in the visa-free trip to Vyborg, Russian Karelia I described in a previous article, where they still, this summer, keep your passport.

With the opening of the Viru in 1972 Finns flooded across the Gulf, and to their mild surprise, found themselves money changers and traders. YLE, the Finnish state broadcaster, says they came with suitcases full of everyday needs for Estonians:

“While useful, even vital to Estonians, the trade also reminded them of their reduced circumstances. ‘Yes, it burdened the Estonians,’ remembers Eva Lille, who led tours to Estonia in Soviet times. It exhausted them, the load of gratitude that came from it.”

In a 2013 article titled A Finnish Trojan horse in Soviet Tallinn, YLE wrote:

“Viru was, in addition to the centre of tourism in Tallinn, local prostitutes’ most visible parade. They came from all over the Soviet Union, and many learned passable Finnish, as it was the main language used with customers.

Sofi Oksanen, a Finnish-Estonian author, tells … of a flight of stairs behind the sofas in the lobby. It allowed prostitutes to flash the soles of their shoes—on which they had written a price—to those sitting on the sofas without raising suspicion.”

•••••

Latvia’s KGB museum, down the coast, depicts a situation far less madcap and much more malign. At the corner of Brīvības and Stabu streets in Riga they weren’t running a covert unit, some mishap-riddled mad scientist routine like the Viru, but an office of interrogation and incarceration, complete with 44 basement cells and an execution room where, in six months in 1941, at least 141 people were shot or bludgeoned to death. Officially Internal Investigation Prison #1, it came to be known to residents as the Corner House.

Latvia’s KGB museum, down the coast, depicts a situation far less madcap and much more malign. At the corner of Brīvības and Stabu streets in Riga they weren’t running a covert unit, some mishap-riddled mad scientist routine like the Viru, but an office of interrogation and incarceration, complete with 44 basement cells and an execution room where, in six months in 1941, at least 141 people were shot or bludgeoned to death. Officially Internal Investigation Prison #1, it came to be known to residents as the Corner House.

From the museum:

“Occasionally, the prisoners would be taken, one cell at a time, to the small ‘exercise yard.’ There they could walk for approximately twenty minutes – single file, in a circle, hands behind their backs – no talking, no stopping, no sitting.

The yard had metal grating covering the top, and an elevated walkway was built so that an armed guard could observe the prisoners. In the winter, snow was removed from the yard so that prisoners could not hide notes in the snow.

Despite these conditions, visits to the exercise yard were welcomed, as they were the prisoners’ only contact with daylight and fresh air, as well as an opportunity to move about and escape the confines of the cell.

The execution area, the museum says,

“consisted of a large room fitted with garage doors in which trucks could back up. An adjoining small room was lined with timber and padded to muffle sounds. The walls were covered with a black, rubberized fabric. A drain for blood was installed in the corner of the tiled floor. During executions, truck engines would be turned on to drown out the noise of the shots. … A small calibre (6.35 mm) pistol was used to prevent excessive spattering of blood and brain matter; often more than one shot was needed to kill the prisoner. … [T]he Museum … has knowledge of at least 186 victims.”

Visit for a tour of the cells downstairs, and a continuous loop of remarkably feisty first-person video testimony from now-elderly survivors of the cells in the basement.

•••••

Where Tallinn is tiny, Riga spreads across either side of the Daugava river, a sprawling polyglot of a city. A former Hanseatic trading cousin of Gdansk and Visby Island and Stockholm, from the 13th century Riga has brokered commodities from the hinterland in the direction of Smolensk and Belarus for manufactured western Baltic goods.

Today, Latvians only outnumber ethnic Russians 44% to 37%, with attendant squabbles over questions of citizenship and language. The pro-Russian Mayor Nils Ušakovs was sacked in a corruption scandal back in April, around which time a survey showed “80 percent of Latvian-speaking readers favoured the dismissal whereas 70 percent of Russian readers opposed it.” Credit a city so divided for supporting (largely through grants and volunteers), a KGB museum.

Preferring just to look past the whole Soviet era, the Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation presents Riga from prehistory until an abrupt end in 1940, the year the Soviets invaded. Latvia made much of 2018 as the centenary of its statehood after World War I.

•••••

There is a hint of the pagan in Latvia, a lingering mysticism kin to the flourishing Icelandic Ásatrú. It’s seen in the pre-Christian themes of Latvia’s ancient folk songs, the Dainas, typically little four line musical poems, a sort of Latvian haiku, like this:

Trim kārtām zelta josta

The golden belt has three layers

Ap resno ozoliņu

Around the fat [giant] oak

Ne tam līda svina lode

No lead plumb touched it

Ne tērauda zobeniņis

Nor any sword of steel

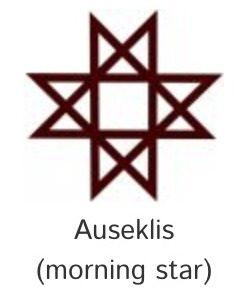

The Auseklis, or Morning Star, is the very rough medieval equivalent of the Turkish Evil Eye, used to ward off trouble. It became identified as a symbol of Latvian national reawakening in the 1980s, at the time when the entire former East Bloc gradually began to stir.

The Auseklis, or Morning Star, is the very rough medieval equivalent of the Turkish Evil Eye, used to ward off trouble. It became identified as a symbol of Latvian national reawakening in the 1980s, at the time when the entire former East Bloc gradually began to stir.

The dominant theme in the Riga Cheka Museum (the KGB was called the Cheka at the time it used the Corner House) is open defiance of the Soviet order. Contemporaneously, the audacious 1979 visit of the first Polish Pope, John Paul II to eight Polish cities led to the rise of the Solidarność movement, and no visitor can miss the unsettlingly tall Solidarność monument outside the Gdansk shipyard where the movement flourished. But in southern Poland resistance operated more covertly.

In Wrocław, a cozy little restaurant just off Solny Square also bills itself a “historical education center.” In a nice touch, covertly placed behind a cabinet at Konspira is a repository of artifacts from the Solidarność uprising, walls lined with newspaper accounts, surreptitious communications gear (how outdated it looks now!), riot shields and helmets.

In Wrocław, a cozy little restaurant just off Solny Square also bills itself a “historical education center.” In a nice touch, covertly placed behind a cabinet at Konspira is a repository of artifacts from the Solidarność uprising, walls lined with newspaper accounts, surreptitious communications gear (how outdated it looks now!), riot shields and helmets.

Konspira’s clever menu explains the state of affairs in Poland at the beginning of the 1980s and claims that “the symbol of ‘dove of peace’ was created in Hotel Monopol in Wrocław where, on a restaurant napkin in 1948 it was sketched by the then member of the French Communist Party … Pablo Picasso.” Konspira claims that in his spirit “The Freedom and Peace Movement was created by activists … primarily involved in protecting recruits refusing to serve or take the oath of ‘faithful service to the Soviet Army’” in occupied Poland.

Honorable Mention: in Kiev, drop by Остання Барикада (The Last Barricade), or “OB” beneath Maidan Square, the locus of the students revolution in 1990, Orange revolution in 2004 and what they call the Revolution of Dignity that ousted President Viktor Yushchenko in 2014. Behind an unlikely entrance door (photo), OB requires a kitschy password to enter (email me) and serves up mementos from Ukraine’s revolutions, along with traditional pelmeny, salo, and locally produced sausages and cheeses.

Honorable Mention: in Kiev, drop by Остання Барикада (The Last Barricade), or “OB” beneath Maidan Square, the locus of the students revolution in 1990, Orange revolution in 2004 and what they call the Revolution of Dignity that ousted President Viktor Yushchenko in 2014. Behind an unlikely entrance door (photo), OB requires a kitschy password to enter (email me) and serves up mementos from Ukraine’s revolutions, along with traditional pelmeny, salo, and locally produced sausages and cheeses.

•••••

Photos © Bill Murray Voices, Inc. except top photo of the Baltic Way protest in Lithuania, courtesy Wikimedia Commons and Rimantas Lazdynas [CC BY-SA 3.0]