by Eric Miller

Tickets

How apt that the person responsible for handling tickets to a Museum of Anthropology should herself sit in a vitrine! You cannot get in for free to an exhibition, how else could the museum sustain itself? It is an enterprise. Compensation is fair. History being what it is, we do not have paper tickets, we have electronic ones. But, behind her laminations of glass and transpicuous plastic, the ticket woman has trouble scanning with her hand-held device our shyly displayed, ephemeral glyph. Only the diligent device can verify it, this woman herself could not puzzle it out any more than we can. Shaped to please the palm that enfolds it, the mechanical keeper of the threshold emits an intelligent-looking, candy-coloured beam. How photodynamic the act of entry has become! I have noticed, however, and on more than one occasion, the speed of light is hard to match in daily life. True, that standard (or rather that hope) is a shade unrealistic. At present, a brilliant little ray, unbending, as thin as a wire, concentrating hard, is only supposed to okay an insignia flashed upon our opposing screen.

Exasperated with the impasse and with the beam—which, to be fair, looks credibly intense—, the ticket woman sighs, sighs, snaps at us and glares. Her eyes are more lancing than a laser. Her glance stings like splashed vinegar. No, we cannot possibly really possess the tickets we say we have. Then a beep like a nuthatch’s, a synthetic syllable blurted by her scanner, deems us, none too soon, to be admissible after all. Passing thus is always a relief, I began to mistrust us myself. Who knows what we were up to! Did you ever work a fair? I was still a kid when I worked, not very hard at all, at a Maytime fair. Read more »

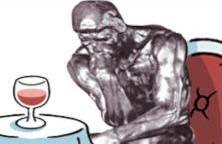

Philosophy has been an ongoing enterprise for at least 2500 years in what we now call the West and has even more ancient roots in Asia. But until the mid-2000’s you would never have encountered something called “the philosophy of wine.” Over the past 15 years there have been several monographs and a few anthologies devoted to the topic, although it is hardly a central topic in philosophy. About such a discourse, one might legitimately ask why philosophers should be discussing wine at all, and why anyone interested in wine should pay heed to what philosophers have to say.

Philosophy has been an ongoing enterprise for at least 2500 years in what we now call the West and has even more ancient roots in Asia. But until the mid-2000’s you would never have encountered something called “the philosophy of wine.” Over the past 15 years there have been several monographs and a few anthologies devoted to the topic, although it is hardly a central topic in philosophy. About such a discourse, one might legitimately ask why philosophers should be discussing wine at all, and why anyone interested in wine should pay heed to what philosophers have to say.

Every Democrat, and many independent voters, breathed an enormous sigh of relief when Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump in the November election. Now they are all nervously counting down the days (16) until the last of Trump’s frivolous lawsuits is dismissed, his minions’ stones bounce of the machinery of our electoral system, and Trump is finally evicted from the White House. Only then can we set about repairing the very significant damage that Trump and Trumpism have wrought upon our republican (small r) and democratic (small d) institutions.

Every Democrat, and many independent voters, breathed an enormous sigh of relief when Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump in the November election. Now they are all nervously counting down the days (16) until the last of Trump’s frivolous lawsuits is dismissed, his minions’ stones bounce of the machinery of our electoral system, and Trump is finally evicted from the White House. Only then can we set about repairing the very significant damage that Trump and Trumpism have wrought upon our republican (small r) and democratic (small d) institutions. Three times have we started doing philosophy, and three times has the enterprise come to a somewhat embarrassing end, being supplanted by other activities while failing anyway to deliver whatever goods it had promised. Each of those three times corresponds to a part of Stephen Gaukroger’s recent book The Failures of Philosophy, which I will be discussing here. In each of these three times, philosophy’s program was different: in Antiquity, it tied itself to the pursuit of the good life; after its revival in the European middle ages it obtained a status as the guardian of a fundamental science in the form of metaphysics; and when this metaphysical project disintegrated, it reinvented itself as the author of a meta-scientific theory of everything, eventually latching on to science in a last attempt at relevance.

Three times have we started doing philosophy, and three times has the enterprise come to a somewhat embarrassing end, being supplanted by other activities while failing anyway to deliver whatever goods it had promised. Each of those three times corresponds to a part of Stephen Gaukroger’s recent book The Failures of Philosophy, which I will be discussing here. In each of these three times, philosophy’s program was different: in Antiquity, it tied itself to the pursuit of the good life; after its revival in the European middle ages it obtained a status as the guardian of a fundamental science in the form of metaphysics; and when this metaphysical project disintegrated, it reinvented itself as the author of a meta-scientific theory of everything, eventually latching on to science in a last attempt at relevance.

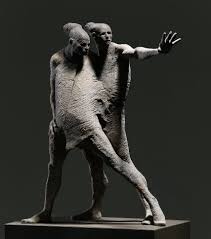

For the past few years, I’ve been taking a fairly deep dive into attempting to understand the physical and ecological changes occurring on our planet and how these will affect human lives and civilization. As I’ve immersed myself in the science and the massive societal hurdles that stand in the way of an adequate response, I’m becoming aware that this exercise is changing me, too. I feel it inside my body, like a grey mass coalescing in my chest, sticking to everything, tugging against my heart and occluding my lungs. A couple of months ago, I decided to stop writing on this subject, to step away from these thoughts and concerns, because of their discomfiting darkness.

For the past few years, I’ve been taking a fairly deep dive into attempting to understand the physical and ecological changes occurring on our planet and how these will affect human lives and civilization. As I’ve immersed myself in the science and the massive societal hurdles that stand in the way of an adequate response, I’m becoming aware that this exercise is changing me, too. I feel it inside my body, like a grey mass coalescing in my chest, sticking to everything, tugging against my heart and occluding my lungs. A couple of months ago, I decided to stop writing on this subject, to step away from these thoughts and concerns, because of their discomfiting darkness.

If one enters the name “Ellen Page” into the search box at

If one enters the name “Ellen Page” into the search box at  Arma virusque cano: Sing,

Arma virusque cano: Sing, This Christmas, I stayed in a Marriott in the town where my kids live. Like most people, my business and personal travel has mostly ground to a halt in the last 9 months. So I was pleasantly surprised by the check-in experience the hotel provided me to allow for social distancing. I’m a long-time Marriot member and have their app on my phone. Using it, I was able to check-in ahead of time, and when my room was ready, they sent me a mobile key.

This Christmas, I stayed in a Marriott in the town where my kids live. Like most people, my business and personal travel has mostly ground to a halt in the last 9 months. So I was pleasantly surprised by the check-in experience the hotel provided me to allow for social distancing. I’m a long-time Marriot member and have their app on my phone. Using it, I was able to check-in ahead of time, and when my room was ready, they sent me a mobile key.  In the early months of 1966, whenever a familiar look of boredom settled in my mother’s eyes at the thought of cooking, I’d suggest, “Why don’t we go out for pizza?”

In the early months of 1966, whenever a familiar look of boredom settled in my mother’s eyes at the thought of cooking, I’d suggest, “Why don’t we go out for pizza?”

Adlai Stevenson, in the concession speech he gave after being thoroughly routed by Ike in the 1952 Election, referenced a possibly apocryphal quote by Abraham Lincoln: “He felt like a little boy who had stubbed his toe in the dark. He said that he was too old to cry, but it hurt too much to laugh.”

Adlai Stevenson, in the concession speech he gave after being thoroughly routed by Ike in the 1952 Election, referenced a possibly apocryphal quote by Abraham Lincoln: “He felt like a little boy who had stubbed his toe in the dark. He said that he was too old to cry, but it hurt too much to laugh.”