by Eric Miller

Tickets

How apt that the person responsible for handling tickets to a Museum of Anthropology should herself sit in a vitrine! You cannot get in for free to an exhibition, how else could the museum sustain itself? It is an enterprise. Compensation is fair. History being what it is, we do not have paper tickets, we have electronic ones. But, behind her laminations of glass and transpicuous plastic, the ticket woman has trouble scanning with her hand-held device our shyly displayed, ephemeral glyph. Only the diligent device can verify it, this woman herself could not puzzle it out any more than we can. Shaped to please the palm that enfolds it, the mechanical keeper of the threshold emits an intelligent-looking, candy-coloured beam. How photodynamic the act of entry has become! I have noticed, however, and on more than one occasion, the speed of light is hard to match in daily life. True, that standard (or rather that hope) is a shade unrealistic. At present, a brilliant little ray, unbending, as thin as a wire, concentrating hard, is only supposed to okay an insignia flashed upon our opposing screen.

Exasperated with the impasse and with the beam—which, to be fair, looks credibly intense—, the ticket woman sighs, sighs, snaps at us and glares. Her eyes are more lancing than a laser. Her glance stings like splashed vinegar. No, we cannot possibly really possess the tickets we say we have. Then a beep like a nuthatch’s, a synthetic syllable blurted by her scanner, deems us, none too soon, to be admissible after all. Passing thus is always a relief, I began to mistrust us myself. Who knows what we were up to! Did you ever work a fair? I was still a kid when I worked, not very hard at all, at a Maytime fair.

There were spools of tickets the size of small wheels, purple, red, blue, white, all colours, with perforated edges and you tore them free. There was too little to do to foster slacking off. Candyfloss, that extravagant seasonal mould, clung to a Neapolitan field of dying ice cream and durable dandelions, the iceless skating rink was piled with rows of second-hand books for sale many of them perverse yet without, sadly, illustrations. True there always impended the fear of losing the precious tickets: sometimes, too, the perforation was too tenacious and the pigmented ticket ripped severely. But here was a favour you might brandish, considering meanwhile how the same ticket might get you pink cream-filled cookies which you knew in advance you would eat too many of too fast, or you could ride on a pony pinioned like Ixion. The animal trod a tight circle like the horses (I have read) who powered an early—a paddlewheel—ferry, the Peninsula Packet, across Toronto harbour. That was the nineteenth century. Some tickets, to go back to that fairground I was just talking of, were crushed under heels in swathes of unlucky grass flattened like lengths of a new-grown, natural tinsel and as soon as the booths were folded, festivities over, all the tickets were trash instantly. You would come across a ticket years later and think, Now I wonder which fair, concert or play that went with: for the format of all such tickets was identical (ADMIT ONE they said). Were we enterprising we might even have sneaked in to entirely different events with the same tickets but now, let me remind you, we are heading—entirely legitimate I don’t need to insist, surely?—where helpful signs promise us Kent Monkman’s exhibition.

Beavers

Have beavers figured in your life? I have not avoided them and I love beaver-ponds, if possible, even more than beavers themselves. This feeling has affinities to how I like art, sometimes, more than I do people. By the way, when a beaver swims it gets the appearance of being really wet. Were it a dog it would shake the drench off on the shore but I do not believe I have witnessed a beaver shake itself in this manner or for this reason. In respect of the factor of sodden-ness, at least, a beaver coming out of the water resembles a cormorant, a stringy-looking fish-eating bird that soaks completely. Just the other day I saw several cormorants standing upon stumps lifting from the shallows of a lake (named what else than Beaver Lake) hanging their laundry wings out to dry and, to hasten this end, vibrating them slightly—as a Venetian blind buzzes before a breezy open window. Whereas after a loon dives, a creature in sleek contrast to a beaver and a cormorant alike, it emerges dry-looking at once, as though it had no acquaintance with water even while it paddles with ebon, hidden feet through that very medium. The oil from the bird’s uropygial gland, distributed dotingly by the bird itself over the entirety of its lovely body, operates as a hydrofuge. Is that the word? One of my favourite beaver-ponds—or series of beaver-ponds (immemorial, castorial terracing debouching into a bay off a bay off Georgian Bay)—hosted amid its alders, its poplars, its rushes and its upright stubs nests of Chestnut-sided Warblers, American Redstarts, Yellowthroats, Kestrels, Hooded Mergansers, Tree Swallows, Flickers, Black-billed Cuckoos, Eastern Kingbirds, Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers, White-throated Sparrows, Song Sparrows, even Lincoln’s Sparrows (a rarity under the circumstances, bedded on saturated sphagnum that rippled fragrantly as though pleased and suppressing that pleasure). Those were the days! So are these ones, I am happy to add, to allay any anxiety you may feel on that account.

What the Baron said

It so happens I was translating an old German named Johann Georg Sulzer and he went so far as to translate an old Frenchman Baron de la Hontan who, discussing the beavers of la Nouvelle-France, advanced the following, broadly plausible claims: Beavers seek out a place with some superfluity of their preferred nutriment. It lies where water runs and gives these creatures the opportunity of developing a reservoir in which they may swim without vulnerability to molestation. To fashion a dam is the first labour that confronts them. Along the dyke, they erect the wattle and daub of their hutch, its threshold flush with the surface of the pool they have projected. The dam’s base attains a breadth of ten or twelve feet. Where it faces the filling basin the dam slopes, the inclined mass stoutly buttressed into the ground beneath. Its farther side stands perpendicular, as do our walls. The structure everywhere tapers toward the top, until it measures just two feet across. Wood and coarse clay comprise the majority of the materials. With an appearance of reason, the animals cut branches to sizes answering specific architectural requirements. A man’s arm gives a good idea of the average circumference of the lumber they use. They fix one end into the earth, cramming the gaps between trunks and boughs with petty stuff. But because the stream could still force a way through—and their intended lake remains dry—they stop up the frame or lattice-work inside and outside with the clay they manage so artfully. To alter the level of their managed flood, beavers adapt the height of the bulwark as necessary. If high water overtops the dyke—or hunters rupture a portion—repairs to that sector are expeditiously wrought. Vigilance scans, craft ramifies, and patience fortifies the whole.

Reader, don’t you love a turn of phrase such as “a man’s arm gives a good idea of the average circumference”? That is how to do it, my dear Baron: so precisely imprecise! What resource do we have but this palpitant unit of measurement, this body? Let us go walking, arm in arm, past the sweet gale, round the juniper with its spiral arms and its purple berries, and underneath the stately sugar maples, wiping away (like tears) each other’s mosquitoes.

Old masters

It has fallen to Kent Monkman, an artist of Cree and Irish parentage born at Interlake in Manitoba in 1965, to teach his viewer the history he reconsiders. It is not that we haven’t known these things before, it is that we fail to retain them. The mind, though it pools, holds less than a beaver-dam—mine does, at any rate. The mere present is so awesomely persuasive. Monkman recalls for us (among other things) that Canada, from the standpoint of those who lived in these parts before Europeans arrived, emerged from the freak fusion of a pair of monomanias, for a single God and for beavers. Monomania, say the diagnosticians, is a form of melancholy. How sad therefore the Company of Adventurers of England Trading into Hudson’s Bay, how distrait la Compagnie des Cent-Associés and the Nor’Westers! The monomaniac desires yet once more (can you believe?) to convert strangers to the assistance of an irremediably lonely God: the monomaniac desires to divest that beaver again, and again, and again of its intimate pelt. The passion! Can’t leave either alone. Can’t give either up. A monopoly (on the one hand) of negation and (on the other) of affirmation. How pleasant to address a prayer somewhere (the cold exhalation hovering like incense before the lips of the worshipper): how pleasant (alternatively) to stroke the rind of a palpable beaver. God keeps evading the trap (don’t worry, a martyr always stands ready to take his place), whereas once we have extirpated the rodent locally, the land no longer bearing the one true fur, we persist, we wester, we shuffle and we fire after the retreating train of the homely waffle tail.

In a word, the public is no less deviant than the private. Never forget! If a solitary man behaved thus, we would call him crazy. We live as though there were no tomorrow and as if there were no yesterday, either. We are present, and unaccounted for. At least a history painting, whether it features Benjamin West’s James Wolfe or Monkman’s Miss Chief Eagle Testicle, makes plain its perennially restless refutability and irrefutability. Like God and like a flayed beaver, there it is: as taut as can be upon a frame. We have the freedom to see what we happen to see. A gallery, then, is a humane trap-line of a kind, what is caught this morning is not what was caught last week or last month or last year, we are captivated yet we are freed.

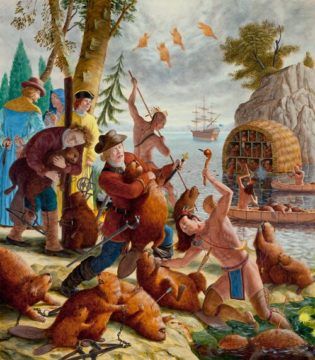

The first room of Monkman’s exhibition plays on what became Canada’s early, close-coupled obsessions: a divinity, rodents. Ever and again a cross wracks God, a hoop excruciates a beaver-skin. In this connection, you have to know how Matthew, the evangelist, says Herod the Great, fearing (a little like Kronos in his time) to be dethroned by Jesus Christ, ordered the killing of all boys under the age of two in the neighbourhood of Bethlehem. And this fabulous ordinance or its consequence got called throughout Christendom the Massacre of the Innocents, and painters such as Bruegel the Elder and Raphael and Rubens depicted it. But (in Monkman’s rendition) the innocents in question are beavers, harried for their pelts. Teeming beaver-souls, multitudinous in demise, levitate into heaven, released from their lives less valuable than their fur. Monkman catches the expression of faces of people who think they have managed to catch something for good for themselves, and stop it, and turn it to their ends, which they think clear. Got you now. Acts of persuasion and of self-persuasion! Back then, people would not let up any more than they let up these days. We all proceed by gross overemphasis, don’t we? Till what we emphasized no longer exists in a sufficiency answering to our strange, outrageous purpose. Me, I own not a thing confected of a beaver. I did hanker, as a kid, to try on a beaver hat. Now let me confess, I do not consult here what Monkman himself says in explanation of his art, I improvise on the instrument his kindness and his skill has provided. What I love, what I love him for, is the opportunity of contemplation he tenders us—without monomania, without it (I say) though he offers profuse a gift munificent to us. Puzzled, furious, horny, drolly ab integro past ages he renews. In each piece, he is like the augur who marks out with a staff an open place for observation, he opens in fact that clearing or he makes it apparent. My father, aged six, the Great Depression as hard as the snowpack around him, kept a trap-line, the licence must have descended from his late father to his father’s widow, he consulted this system lone on morning snowshoes (there was the hope of snaring painful money), a lynx stalked him as was, it may be, fair. He never liked, as long as I knew him, ever killing a thing. In this sense, you may say the ambitious lynx got him: but they feed in truth almost exclusively on hares.

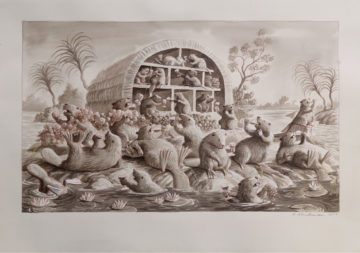

Beaver Bacchanal

Mark Elbroch tells us some beaver dams stretch the breadth of a whole mile: or what we votaries of the metric system will call a kilometre point six. Early etchings of beaver lodges, however, make them appear like the insulae or city blocks of Ostia. Monkman laughs a multifarious laughter in the gap between misprision—itself a truth—, and nature and, glancing aside at Renaissance images of revelry, depicts in “Beaver Bacchanal” the artful rodents lodged just before the moment of their historical eviction, standing in and around their stratified hutch, cups brim with red wine—much as their dam detains the forest’s lymph, topping it up. The idea of wine intoxicates more than the liquor. Bacchus is spirit equally, and spirits. I am inebriated by the thought of drunkenness, rarely have I ever been drunk. This is a common relation to all possible deities and appetites. A concept suffices for the most part, the sip that is the taste of the god. I happily lap the god to the point when the tongue ceases to register the adult acerbity of the grape, taste is over too soon is it not? Beavers build here and there Melancholy’s sovereign shrine and sovereignty, assuredly, is a meaningful matter is it not? Blithe Monkman shows the reciprocity of drinking with urinating, we become fountain statuary there at the pent edge of the reservoir, the happy, happy rodents taste and piss, piss and taste. Alas, a famous rite of Bacchus is σπαραγμός, “sparagmos,” rending, tearing, mangling: which fierce trade in furs in due course visited on the nations of men and women as well as of animals. It is not breast-beating or idle mortification to say so. These things, among other things, happened.

Merchants of Montréal

I have been writing a prose epic of sorts, and one topic I treat is the fur trade. It is 1792, let us visit now with a characteristic fur trader of that late date:

Try to find in Mr. Joseph Frobisher of Beaver Hall classical proportions. Search yields none. The scanning eye has difficulty, as scouting a rumoured portage where there appears no admission to the brush. The puzzling insubordinations of what its frontiers must confirm as the area of his face disrupt from the start any conception of the man. Can you quite see him? No. Pursuing their bent, his lips writhe: even they elude each other. “Twisted” would sound too much like a moral judgement. You could not comprise the wryness easily into a kiss. No part of this man partakes of a parity of form or dimension. His nostrils do not match. That incoherence, his visage, situates in him or his vicinity a beaver-like hutch of enduring dilapidation. Crooked timber lasts best, his grimace stretches like a skin curing. His pent eyes spill with restraint into a world beneath his level. They do not precisely see. They push forward, supplying in their turn a sight the receiving world cannot quite con. The man has no classical, let alone neo-classical, features.

His seeing—like the sight of him—is so opaque that it dims ours to irrationality. Then he himself appears reasonable, very reasonable. Certainly more reasonable than any of us. We keep trying to pin our faces upon him. How blunt the tacks of our eyes are. We lapse into little fits of failed generalization. Generalization is our hasty substitute for the idealizing impulse that cannot usurp Mr. Frobisher’s countenance, though it submits to improve the looks of most everyone else. “Ugly” will not do. I do want to use it, it just will not stick. We must multiply unlikenesses, though through them we do not succeed. The pins sink into our own flesh. He has stressed us out of shape. He is reasonable. What is it that surprises his wide eyes? Their resolution: the resolution. Yes. That is perhaps the continual surprise.

For him, given his physique—I mean the shape of his mind—rejection is the chiefest kind of acceptance to come his way. He stands it in front of him, and he backs it up behind him. He knows it will arrive. The result of this prudent presagement pours from his gaze, like water over the brim of a beaver-dam—coppery, both warm and bitter in hue even when it runs thin, runs cold, sweet, light as a bird-whistle. The birds love a beaver-pond. A beaver knows that she only stalls, she cannot keep: but her act of prevarication, of temporizing, fills the pool of which she is the hairy nymph. Like the aquatic animal, Mr. Frobisher has developed a system. At even the thought of such plenty, an always returning surprise laps him and buoys him. Stubbornness—the emblem is a dam—makes him affluent. What he has to hold, since no one will take it from him, deepens. It pours superfluous dark braids down the dyke. The frustration of being turned away, turning in on himself, turning back, banks his wealth. Behind his eyes, in other words, extends the whole of his North-West Company as far as Lake Superior: in fact, much farther.

Yet he does not behave superior. He is all reason, of a kind. His brinkmanship on the dam’s precipice is like amazingly not losing your footing. Diligent as a beaver, he heaps up the sadness of his thwartedness. That rubbish builds the very bulwark of what makes him Mr. Frobisher. It keeps amassing. Is a forest classical? His triumphant disappointment detains a body as great as Superior itself.

Grand portage by negligible, Mr. Frobisher’s Company sings. Voyageurs call the most colourful songbirds “little beasts.” Like les fauvettes, beasts as bright and bulkless as the sunlight that these sylvan warblers shun, the Company sings. Wrens are no less longwinded than the North-West Company. Like les troglodytes (tail and beak raised to the identical sixty degrees), it sings. Choral thrushes are Pindaric, the Company is no less so. Like les grives tremolo, diminuendo, setting the swamp sugar bush to strophe, to antistrophe, it sings. Or like insatiate flycatchers swarmed by their speck-like diet, it sings. What stings human beings, feeds them. They turn a besieging enmity into plangent suggestion. Short flights of the larger insatiables gulp down those less sizeable. Any kind of wing (like a paddle in water) delves a path in the air. Song signs the air. One singer subsumes another. Swallowing music, they transmit music. So the North-West Company sings: it turns into music. Rough men make fine music. That is what men are for, what men are: only turn into music. Underbrush turns obstruction into fragrance, turbulent men turn into music. We would think Mr. Frobisher led the wilderness in a choir that had awaited the epoch of his tutorial. No one has the means to preserve the songs. The voices vary to match the guilds of wingèd singers. Birds assert an aboriginal right expressed in their music, and by their music. They have been born to certain tastes, and their songs are their law. They have a concept of property. Nature believes in it. They turn it all into music, or they seem to. Nature dictates sharing. In the orchestra, instruments cooperate: but at the end of the performance each is distinctly itself, a form and a weight, a possession. The carol stretches till it strikes its own echo (rock, sand, mud, pebble, or marsh). Does Mr. Frobisher hear his Company singing? No maxim will bear less examination than that Trade should be left to itself.

He handles the brim of a beaver-hat, twists it round as though navigating. He spends half his time at Grand Portage. He steers the North-West Company. The upturned brim of the hat, twisted, turns. It is confected from the floss of a beaver’s guard hairs. Nitrate of mercury, gum Arabic, alder-bark and verdigris have soaked it. At some time that hat swam and where running water gushed, scraped silt and gnawed sticks to construct its own facility: a dam. In flooded stubs, the martin (voluble) and merganser (elegant) and kestrel in her parrot colours lined acridly cavitied each a nest, using one another’s feathers to buffer their sunless clutch. Mr. Frobisher’s cup runneth over, he drops the hat on Miss Sone’s head. Rakish the tilt, he snugs it down. He hesitates (pinched thumb and forefinger) before letting go the brim. The brim! His eyes pour their auburn waters onto the woman, her hair likewise a dark waterfall. Cock up your beaver, she adjusts the set and ravishes the firelit room. But her host wails, I cannot. I cannot stand it.

The Scream

What is it like to obey orders? We have all followed instructions, sometimes it is difficult to do so because they are incomprehensible. Often my forehead has wrung itself grievously, my hands have shaken when a figure in authority has asked me to perform a sequence of actions some of which make no sense whatever to me. You know already! is the commonest reproach I have heard on such occasions. But here I take a stand beside Socrates, sir, ma’am, I know that I do not know. If in fact you can perform some series of imperative actions my congratulations, faithful reader: for isn’t it that we are not to ask the reason why? Ours but to do, and die—or that’s how the rhyme goes. Rhyme is a kind of destiny. How resistible is it?

Soldiers and police especially follow orders, sometimes in fact they conceive of them, they allow civilians moreover to do things at their discretion, “You may do this, it is okay with us,” but soldiers and police of course are answerable eventually for the decisions they make and impart to one another and to civilians. They are not the end of authority, that is supposed to be found elsewhere. Long after a Benjamin West’s pigment has clotted, a Kent Monkman takes up paintbrushes. It’s hard to get away with anything isn’t it? The length of time is important to note, justice, a kind of grammarian, a kind of calculator, calls that “sentencing” or proportionality. Speaking of civilians, I remember one saying something à propos around 2005 when I was visiting the Maritime Museum of Victoria (since closed) and standing with my kids, then four and seven or so, in front of an exhibit consisting of some old safes, their thick doors flung open. A velvet rope defended these safes from us. A gentleman came rather too close to me (I could surmise the condition of his teeth) and he confided, “The police have okayed the pirates you know.” I did not rejoin with a Socratic, “No I don’t know” (never say a word) but as in many such cases (I mean many) I sketched the smile I could not readily fetch onto my features. I have a weakness for cutlasses as objets I freely acknowledge but, consulting history, I protest they had many uses, not all of them piratical. Rare is the pirate or constable today in whose hands you will find a cutlass! Then there was the guy, glasses, moustache, short, slight, hair weakly ginger, aura of a spiteful actuary, whom I kept meeting, it began in 2003, it was usually when I was en route to a recurrent appointment, who would infallibly declare, “Fine weather for ducks!” regardless of circumstances obtaining in the sky. If you say so, inevitably reappearing personage! We all know people like that. Oh no, I should not presume about knowledge or about people. Funny what enters your head. Still, hospitality to the strange and stranger is, of old, our devoir. There is more to this world than God and beavers, cops and pirates. It is our obligation (I will not call it sacred), and our inexpressible relief, to say so.

Kent Monkman may have been punning on the first syllable of his name when he called a painting “The Scream.” Munch means no less than “monk,” after all. Edvard Munch heard, he said, a shriek throughout nature. It rang out in the late nineteenth century. Volcanic Krakatoa obliged the painter by supplying the shrill bloody tropospheric palette to support the daubing of this cry, lofting Indonesian dust high enough into the whole planet’s sky that it reached where the temperature ceases to fall and emboldened Munch’s unusual colour scheme. On site—the Sunda Straits—far Krakatoa, blown like a black rose, all largesse, subsequently offered free lessons in plant-succession to the attentive: a monster as wise in its way as the fabled centaur Chiron.

So Munch’s painting is nature painting that is what it is, called by him “Skrik” or “Der Schrei der Natur.” As for Monkman, his painting features a woman of close to our day screaming, an ecclesiastic has seized a toddler, likely hers, the kid might be five or two or somewhere inbetween: I cannot guess, we recede as quick as tides from the ever-changing palpabilities of paternity undergone, a miraculous sort of drudgery. I recall well how it felt to hoist such a child, incredible as when, once, I pushed a porpoise out from the surf. A couple of Mounties help separate the woman from her offspring. One grips her black hair and her blue dress, the other her arm and a shoulder. At least these gentlemen have the mercy to let her know what is happening, that is not always the case with such gentlemen, they like a little obliquity, sometimes they cherish it for their own reasons. It takes courage here to be so visibly cowardly, but no one should get used to it. The scene transpires on a reservation, the occasion is national education not to be refused, the woman embodies the virtue of στοργή, “storgé,” parental affection. Oftentimes this drive receives the warrant of approval, for example Gilbert White, an early natural historian and (it is true) a bachelor, reproaches the European cuckoo for lacking it, invading other birds’ nests, as it does, and leaving an egg whose chick, when hatched, elbows out the proper residents altogether, who perish. The cuckoos of Canada, I should add, like Mourning Doves and many others, may be slight builders, but they care, as Hal H. Harrison assures us, in their “loosely interwoven” home, for their own brood.

Monkman’s mood is less subjective than Munch’s, observe the birds however, raven, buteo and their activity. Don’t be frightened, offended or triumphant. Neither Munch nor Monkman does more than paint a picture, we know there was a before and an after, we know that authority is there and is not there, we know there is style and history, we are to contemplate, it is possibly the highest pleasure. (Don’t even whisper the word pleasure.)

Occupation

Does the state have a warrant to enter a dwelling in loco parentum? These are our children not yours. It is not that we are the best parents, it is not that we love our children unambiguously, it is not that we do not make mistakes. But suffice to say they are our children, not yours. To which what answer? Anything we say you said will be held against you. We will take a place in your bed too, by the way.

What is it like to obey orders? I have always had a hard time doing that—not from cheekiness or conviction always, it could even be a disorder or so the orderly might deem it (of course they would, we all endorse our own strengths). Perhaps it is invincible ignorance as others (more magnanimously) might call it. Orders are honourable, sometimes. Sometimes, they are dishonourable. Someone issued them: how modest to avert rightful credit! Someone followed them out, shy (likewise) of fame. It’s a wonder but true, sometimes people are both bashful and powerful, or were powerful and are now bashful.

A portion of the sum of orders begins ignoble or plain wrong. That needs adjustment! To ruin a family under the name of rectifying it has been a common public yet intimate employment. The colour of reason has to be worked up while the years pass. They pass. Years on years! It is not even the same people who obey the descendants (if you will) or the remnants of original orders, for those people have aged out of this submission. It is new recruits, who have no idea of the grounds. Kids grow fast. Interfere with them when they are toddlers soon you are interfering with them when they are adolescents and the next thing you know, you are interfering with them after they have achieved womanhood or manhood. Now I was discussing knowledge. People do know what they do not know, their bodies sense it sidelong, centrally and they embody it, the presence of those in the house of their life by whom, if in no other way, they are, in this way, invaded and transmuted. For they incorporate the state. It dyes every cell of their selves. Cell, what a word. The public voice, sometimes extraordinarily—rousingly—unanimous, broadcasts it was for everyone’s good. Everyone is, luckily, no person in particular. I look forward to meeting everyone. But isn’t it a fact a crowd that denounces us can move us with the frail glamour of its frightened, abusive unity? The spectacle even raises our morale. Immortal pleasure!

The demi-possession of a tepid conscience can itself exacerbate the will to protract the infliction of a longer distress. I don’t like to do this so I will do it until I forget why I am doing it. An occupier is properly besieged as time passes that is fair isn’t it? Residential, what a remarkable adjective. A jail cell is often enough an exemplification of the desire to shut people up. It is amazing how many and who can be got superficially to go along with guard duty. A civic triumph who could doubt? A triumph of some kind.

To assimilate is to make like but a simile, as the sons and daughters of Aristotle instruct us, respects the distinction between the vehicle (a red, red rose) and the tenor (my love). In English “like” is a preposition, and the only stable sameness surviving from this comparison to that. It is hard to assimilate in any case to something imponderably metamorphic, onto which the name of the nation is slapped, not indelibly. (Have you heard the slap of a beavertail? This signal abridges distances of water and of time. Leaves flat on water toss, flip up here, there, curled by a gust coincidental, not proceeding from the percussion: a rail rails in the reeds, a bittern—all resourcefulness—draws up depth wells cannot sound: a black tern extends the dimensions of the cove into the humid air above it: a water snake writhes over gneiss-like banded reflections of the shores that skip like stones made to flit bouncing low over wobbling stripes trustworthier than the feignings of stasis. We ourselves undergo a distortion that adonizes us when we lean to see it, the lake a painter obviously, and the sated mosquitoes even keep for the moment to their cloud.) I am glad Kent Monkman came along. I don’t expect the feeling to be mutual.

Défense de fumer

We step outside again, having met at the exhibition, as fate directs we must, a specialist in stained-glass windows. When we visited Castle Howard and stood beside the Temple of the Four Winds, a woman who specialized in stained glass also spoke with us, she had come from Montréal, she had intensity as though she too coloured the world densely wherever she stood: a human prism, in fact, to complement the swarm of bees that depended from a cornice of the Temple as thick, sweet and toxic as the leaden statuary that (impersonating sibyls) took on prophetic lightness—the future’s—, and prophetic heaviness, also the future’s. Today, however, we meet a man who seeks out small churches across Canada and discovers in them neglected, surprising tableaux.

A handsome man, self-deprecatory, his breath savours attractively, yes attractively, of tobacco: a rarity these days, conjuring, in our anthropological context, a now-disposed-of world of nicotine’s associated artifacts. Once upon a schoolday, every friend’s reeking home featured crystalline ashtrays in many configurations, also ashtrays ceramic and metallic, the lares and penates of the roost. Guests, we encountered piquant variety of receptacles heaped with soft invariant smothering cinders, as though smoking were no habit, but rather an admonition that pulvis et umbra sumus, what are we but ash and shade? Altars posed in every room and (after all) tobacco was a sacred plant and remains such for some, though sweetgrass and sage diffuse a more delicious scent. My mother stooped in her youth for a season to tend sandy tobacco fields on the north shore of Lake Erie, it was what young people did in those days to get by. Yet who would not confess one of the most depressing shapes that aftermath can take is cremated cigarettes? Noisomely they scatter, noisomely adhere. I do not smoke and have never smoked, but the gestures associated with the practice prickle my eyes only irritated by love, just as do the marks by which I recognize the flight of a given bird or the tossing of a particular tree. Strange that the strategies by which people soothe themselves, even harm themselves, may be seducing, or I find them so. Yes, homeliness itself blazes with riveting beauty. Cupid’s flame irradiates many vessels. On the site of the Museum of Anthropology (I should note as we take our leave) there stood a Musqueam fort, the garrison surveyed the shining water for war, there is no history, none, stirring whose ashes you will find the absolute absence of the wavering shades of fiend and friend.

Wreck Beach

A beguiling guide, her company as warmly fine as August sand, Carellin Brooks tells us, in her book of the same name, Wreck Beach derives that name from the deliberate sinking offshore, by way of a breakwater, of vessels belonging to the Pacific Tug and Barge Company, in 1928. This enterprise wanted partway to impound tranquil waters for the mustering of logs and, with that in view, scuttled three barges and a floating grain elevator. It might have been fun, this sabordage. We like to go down.

Shouldn’t there be a genre, not bucolic, not georgic, not epic, a little Sapphic assuredly, Anacreontic I would insist, called the littoral? Not the piscatorial, please. Not a hint of Izaak Walton, no hooks, no nets. The circumstance does partake of idyll, for when we tread a beach, following the bare feet of a sibyl such as Ms. Brooks, we become a pining Polyphemus, wheel-eyed, uncouth, wooing sleek Galatea, and frustration—O saline, O hyaline sheen!—is revealed to be, itself, the dizziest of accomplishments, on the coast of everlasting. Languor dallying with stark instinct, we refine from one another most excellent figures. Thus the firm, agreeable activity of renunciation prospers a sentiment of gay abandon, polychromatic reverie. There is none of us, none, not desired by someone or by something—be it only the thirsty air, that wants the wet from our pelts. Ms. Brooks is perfectly honest, she knows that, against any manifestation of the beatitudinous littoral zone, there draw up its deathless enemies: too much and too little rule, those identical ugly twins; and development, worst use of genius possible, hastening to bind the vilest occlusion onto the only thing we have and we are, our bodies—that is to say, our naked senses, their passing opportunity. The wisdom of beaches is this: to refrain is to indulge. Only let us have that from which we must abstain! When she swims Ms. Brooks says she feels “naughty and pure,” that will do for now. Here Kent Monkman’s oeuvre too has pertinence, perched as it is today, acropolis-like, on the bluff above Wreck Beach. Ms. Brooks canvasses the vendors she meets (beer and mushrooms are popular), but among them she makes no place for the monger of scandal or for the camera-man who imagines himself, what folly, invisible. Don’t think evidence is not transitive, every camera points both ways.

And here perhaps we could witness the defeat of surveillance, here we are redeemed by our visibility, we leave off the quest for youth (after all, even youth finds it elusive) and we crave to live every phase of our figure and everyone’s figure, there never was room for a secret, all is simply visionary and the one who would expose others is exposed. This is all I am and this is all you are. It is the only information we were given, and we will ever get. Risibly small life is, yet so much pleasure in it! Step round that calmly contorted stub and the clustering driftwood. Not cormorants there or beavers, but look! that Tacitean villain, the eternal Delator himself, usually so circumspect, surprised in flagrante delicto with the Remorse he always denies he feels, or feels up. Fine weather for ducks, pirate! we might say. Dear reader! Dear reader, let us step into the falling and rising sea, it accepts you, all is acceptable, all admitted, what you were, what you are, what you will be.

But we grow so airily philosophical, and we have not even descended the steps to the shore!

The illustrations are Kent Monkman’s “Beaver Bacchanal” (displayed at the artist’s website); “Les castors du roi” (collection of the Montréal Museum of Fine Arts); and “The Scream” (collection of the Denver Art Museum).