by Dave Maier

If one enters the name “Ellen Page” into the search box at en.wikipedia.org, it redirects to an entry entitled “Elliot Page” (and informs you that it has done this). This is because on December 1, 2020, as the entry itself tells us in the section marked “Personal life,” that person, an accomplished and popular actor nominated for the 2007 Best Actress Oscar for their performance in the film Juno, “came out as transgender on his social media accounts, revealed his pronouns as he/him and they/them, and revealed his new name, Elliot Page.” Naturally this led to a flurry of activity on the interwebs, much of it, not surprisingly, about gender politics. This post, however, will be not be about that, except incidentally; instead, it concerns the much sexier topic of the semantics and metaphysics of naming, and will most likely (you have been warned) finish up with lengthy citations from the relevant sections of Philosophical Investigations.

If one enters the name “Ellen Page” into the search box at en.wikipedia.org, it redirects to an entry entitled “Elliot Page” (and informs you that it has done this). This is because on December 1, 2020, as the entry itself tells us in the section marked “Personal life,” that person, an accomplished and popular actor nominated for the 2007 Best Actress Oscar for their performance in the film Juno, “came out as transgender on his social media accounts, revealed his pronouns as he/him and they/them, and revealed his new name, Elliot Page.” Naturally this led to a flurry of activity on the interwebs, much of it, not surprisingly, about gender politics. This post, however, will be not be about that, except incidentally; instead, it concerns the much sexier topic of the semantics and metaphysics of naming, and will most likely (you have been warned) finish up with lengthy citations from the relevant sections of Philosophical Investigations.

My immediate reaction, that is, when I heard this, was to wonder whether and in what sense “Ellen Page” is still a referring expression, and who gets to decide this, and on what grounds. Naturally Elliot himself has a unique and in some ways authoritative perspective on this, but a) he’s only one of an entire community of English speakers; and b) if he wants to give us a theory of the reference of proper names he’s entirely welcome to do so, but in that context his own perspective, as in (a), is, I think, less authoritative than on the rather narrower question of what he should now be called, which I grant is up to him.

So I’m thinking about sentences like

1) The star of Juno is Ellen Page.

2) Ellen Page is the star of Juno.

3) The first-billed actor in the credits of season 1 of The Umbrella Academy is Ellen Page.

Are these true? False? Nonsensical? Rude to Elliot but otherwise okay? What do they mean? Did they change their meanings on December 1, 2020? What else might we say about them?

How about

4) Ellen Page does not exist.

5) Elliot Page did not exist until recently.

or even

6) When Elliot Page was a little girl, he skinned his knee badly.

7) When Elliot Page reached puberty, his ovaries were perfectly normal, but he didn’t start menstruating until rather later than the other girls in his class at school.

Now these last do depend for their truth value on facts not in evidence (I made them up), but that’s clearly not what’s wrong with them (if anything is). They sure sound funny; but as I always like to point out in such cases, when something unusual happens, whatever you say about it may sound funny.

Okay [*cracks knuckles*], let’s get started.

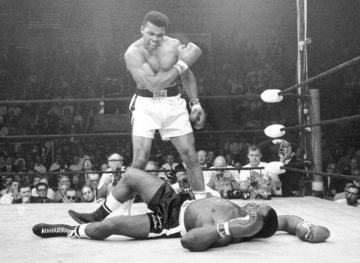

Of course people change their names all the time, and the semantic and metaphysical issues have been debated for centuries; but the bit about the pronouns does give it a new twist. Let’s start with some more familiar examples. Sometimes people change their names to mark an important change in their lives. The men born Cassius Clay and Lew Alcindor, for example, manifest commitments to one or another form of Islam in their new names, Muhammad Ali and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar respectively. However, this need not prevent us from continuing to use the former names. UCLA records will still refer to Alcindor, and one refers quite naturally as well to the memorable Clay-Liston bouts. On the other hand, we may surely use the new names as well, as once one knows what has happened, no confusion arises. When Ali [i.e. that person, who went by “Cassius Clay” at the time, as we presumably need not explain] fought Liston the second time, he knew what to expect. When Kareem was at UCLA, he had not yet perfected the sky hook.

Of course people change their names all the time, and the semantic and metaphysical issues have been debated for centuries; but the bit about the pronouns does give it a new twist. Let’s start with some more familiar examples. Sometimes people change their names to mark an important change in their lives. The men born Cassius Clay and Lew Alcindor, for example, manifest commitments to one or another form of Islam in their new names, Muhammad Ali and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar respectively. However, this need not prevent us from continuing to use the former names. UCLA records will still refer to Alcindor, and one refers quite naturally as well to the memorable Clay-Liston bouts. On the other hand, we may surely use the new names as well, as once one knows what has happened, no confusion arises. When Ali [i.e. that person, who went by “Cassius Clay” at the time, as we presumably need not explain] fought Liston the second time, he knew what to expect. When Kareem was at UCLA, he had not yet perfected the sky hook.

Indeed, multiple naming possibilities allow semantic nuances formerly unavailable. I don’t have to specify that I am referring to Ali’s early career if I say, for example, that Cassius Clay relied on brute force rather than boxing tactics; that implication is clear from my choice of name. I may even, during Ali’s later career, express my belief that the mature fighter consciously spurned his earlier approach by saying that Cassius Clay no longer exists.

Even this much, believe it or not, is controversial. There had always been a worry about the reference of names, as in sentences like “Pegasus does not exist.” If the name gets its meaning from the thing it refers to, then how can such a sentence, which asserts non-existence, be meaningful at all? In 1905 Bertrand Russell famously analyzed such problematic sentences as “The present king of France is bald” by taking the apparent referring expression in the subject to contain a hidden assertion, allowing us to see the sentence not as problematically meaningless but instead as straightforwardly false. If we take proper names (like “Pegasus”) to be implicit descriptions (like “the winged horse”), then these sentences too can be so analyzed, solving the problem.

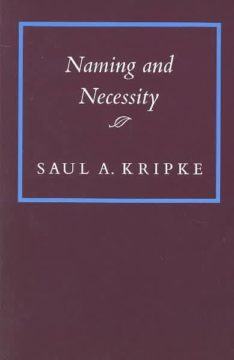

But not so fast! If names are simply descriptions, then another problem arises. Saul Kripke caused quite a stir in analytic philosophy in Naming and Necessity (1980), a powerful attack on the description theory. Mathematician Kurt Gödel, for example, is best known for his famous proof. If, as Russell suggests, a name is defined by a description, then we might decide that the description in question here would be “the guy who proved the Incompleteness Theorem.” But as Kripke points out, it remains intelligible (if not likely) that we have this wrong: maybe (as we believe the English language allows us to put it) Gödel didn’t actually write that paper, but instead ripped off some other, unknown, mathematician (let’s call him Schmidt) and presented it as his own. Now “Gödel proved the incompleteness theorem,” which on the description theory comes out true by definition, turns out to be empirically false: it wasn’t Gödel after all, it was Schmidt. Oops!

But not so fast! If names are simply descriptions, then another problem arises. Saul Kripke caused quite a stir in analytic philosophy in Naming and Necessity (1980), a powerful attack on the description theory. Mathematician Kurt Gödel, for example, is best known for his famous proof. If, as Russell suggests, a name is defined by a description, then we might decide that the description in question here would be “the guy who proved the Incompleteness Theorem.” But as Kripke points out, it remains intelligible (if not likely) that we have this wrong: maybe (as we believe the English language allows us to put it) Gödel didn’t actually write that paper, but instead ripped off some other, unknown, mathematician (let’s call him Schmidt) and presented it as his own. Now “Gödel proved the incompleteness theorem,” which on the description theory comes out true by definition, turns out to be empirically false: it wasn’t Gödel after all, it was Schmidt. Oops!

Kripke unpacked his view in terms of the metaphysics of modality (that’s the “necessity” part in his title). It is presumably only a contingent fact about whoever proved the theorem that he did so. Yet he would still be the same person even if he had not. This is what allows us to say things like “Gödel [that is, that guy] would not have proved the incompleteness theorem if he hadn’t proved [such-and-such other theorems] first.” Kripke thus argued that we need a way to pick out our guy in terms of his necessary properties, to make sure that the reference remains stable enough to speak intelligibly about alternate metaphysical possibilities. His candidate for same was the fact that whatever else might be true of him, Kurt was his parents’ little boy (as I recall – the book’s around here somewhere – the word “zygote” was used).

Such arguments, including but not limited to Kripke’s, then move from names to natural kind terms (“gold,” “water”), and descend from there into dodgy essentialist metaphysics, but even what they say about names doesn’t seem quite right. I don’t remember Kripke himself using this example, but I have seen such views elaborated in the following way. Consider these sentences:

8) Clark Kent is a mild-mannered reporter for the Daily Planet.

9) Superman is a mild-mannered reporter for the Daily Planet.

or even

10) Kal-el is a mild-mannered reporter for the Daily Planet.

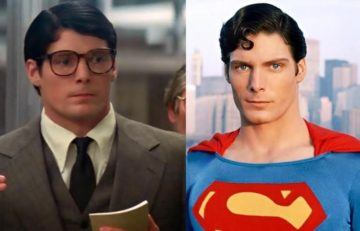

On the view in question, these names, in referring at all, necessarily refer to the same individual, and these sentences must thus have the same truth value: that person is or is not so employed. But (in some versions of the story) Lois does not realize that the man she knows as Clark Kent is in fact identical with Superman (whose birth name, in turn, she may or may not know). For her, then, (8) is true, (9) is false, and presumably (10) as well, even if she does not equate it to (9). But this is a function of her lack of knowledge of the world, not (or only as a result of same) of the meaning of names. We who know better must regard them as synonymous and thus equally true.

Or so the story goes. When I first heard this, though, my reaction was to say that even if she does know the relevant identity (as in some versions of the story), Lois may agree with (8) but not with (9). In this photo, in other words, Clark is the guy on the left, and Superman is the guy on the right. Granted, there is a particular, important sense in which the two men are identical; but there are many others in which they are not. Only a perverse metaphysics, and an equally perverse semantics, whose only virtue is to cement that dodgy metaphysics into the structure of our language, forbids us from using these terms to refer intelligibly to the latter characteristics should we so desire. “Clark Kent is a sharp dresser.” “The traitor Kal-el is somewhere on this planet, but we don’t know where.” “Superman is my favorite superhero.” For these purposes, knowledge of the relevant identities is irrelevant. As I put it above, the multiple referring expressions provide greater expressive opportunities should we decide to take advantage of them.

Or so the story goes. When I first heard this, though, my reaction was to say that even if she does know the relevant identity (as in some versions of the story), Lois may agree with (8) but not with (9). In this photo, in other words, Clark is the guy on the left, and Superman is the guy on the right. Granted, there is a particular, important sense in which the two men are identical; but there are many others in which they are not. Only a perverse metaphysics, and an equally perverse semantics, whose only virtue is to cement that dodgy metaphysics into the structure of our language, forbids us from using these terms to refer intelligibly to the latter characteristics should we so desire. “Clark Kent is a sharp dresser.” “The traitor Kal-el is somewhere on this planet, but we don’t know where.” “Superman is my favorite superhero.” For these purposes, knowledge of the relevant identities is irrelevant. As I put it above, the multiple referring expressions provide greater expressive opportunities should we decide to take advantage of them.

Let’s get back to Elliot Page. With respect to sentences (4) and (5) above, just as with the comparable sentences about Alcindor and Clay, we may use the difference in referring expressions to mark the relevantly different time-slices of that person’s life. This allows us to utter (4) intelligibly about someone still alive, and (5) about someone already in his 30s. Also, as before, we may take ourselves not simply to note the name change, but also to make a further implication about that person’s self-understanding, suggesting that the cause of the name change at that time was a realization that an important line had been crossed, one presumably having to do with gender identity. Similarly, the music critic born William Roberts meant by his adoption of a new pen name, under which he wrote his most well-known books, to signify his resolve to be an “earnest new man.”

With this in mind, sentences like (1) – (3) – as we might have expected – cannot be condemned or accepted just as they are, but require context for them to be interpreted properly. Maybe the speaker is pointedly reaffirming traditional gender distinctions (or another kind of essentialist metaphysics). Or maybe they’re reminding us that Elliot’s former identity won’t just vanish into thin air. Theories of meaning are theories of interpretation, and require a sense of the interdependence of what someone is saying and why they are saying it (and thus of how the world is, and how we might react to it). Not a priori metaphysics!

The same goes for the other two. (7) in particular might look like something Jordan Peterson would complain about being forced by PC commissars to say, on pain of cancelling. I don’t think that’s really a worry though. You could say this if you want – there’s a natural interpretation on which it simply says that that fact is true of that person (which, again, I have no reason to believe is actually the case) – but in the context, it should surely be okay to sidestep odd-sounding locutions like “his ovaries” (and indeed Elliot has indicated “they/them” as acceptable pronouns as well, although as I’ve suggested I think one could make a case for “her” here too). Just as with names, the key point is, as Wittgenstein puts it (more about him in a bit; this is PI §79), “Say what you choose, as long as it does not prevent you from seeing the facts” (which, I would add, may include facts about what attitudes about gender are in play in the context).

One final thing about Page. What if instead of “Elliot,” which allows him to keep the same initials, he had chosen a different name – one which, say, if someone called out his previous name, he could pretend to have heard instead, due to its similar sound? Then in addition to sentences like “When Alan Page was a little girl, […]” we’d have to consider

One final thing about Page. What if instead of “Elliot,” which allows him to keep the same initials, he had chosen a different name – one which, say, if someone called out his previous name, he could pretend to have heard instead, due to its similar sound? Then in addition to sentences like “When Alan Page was a little girl, […]” we’d have to consider

11) Alan Page is a member of the National Football League Hall of Fame.

and

12) Alan Page was the first African-American member of the Minnesota Supreme Court, serving from 1993 to 2015.

Here, as before, you’d need to know something about the world in order to know how many different people we’re talking about. It’s pretty obvious that (11) and (12) aren’t about the star of Juno, but are they about the same person? [Answer: yes they are.] “Alan Page is my hero” would naturally require disambiguation, where before it presumably did not (although there are no doubt plenty of admirable people with that name). So no particular philosophical issues here, although I think the essentialist might have to do some fast talking.

Finally, back to Wittgenstein for the moral. In the early sections of Philosophical Investigations, between the opening discussion of the “Augustinian” conception of language, on which the meaning of a word is “the object for which the word stands” (§2), and the extended discussion beginning at §89 of the question “in what sense is logic something sublime?”, Wittgenstein addresses the issue of naming. At §37 he points out that the relation between a name and the thing named may be any one of a number of things. At §43 he famously notes that “for a large class of cases—though not for all—in which we employ the word ‘meaning’ it can be defined thus: the meaning of a word is its use in the language.”

Wittgenstein is thus often taken to advocate a “use-theory of meaning,” as if the thought were that meaning isn’t reference (or whatever else), it’s use, so that’s what our theory of meaning should say. In the context, though, it’s pretty clear that he’s saying instead that since the phenomenon philosophers are trying to theorize is one of people using words to do things – that is, not simply to refer to things or to state truths, but to express their beliefs and other attitudes, as well as to bring about different states of affairs – we should not expect our account of meaning to be a theory which captures the Single Thing That Meaning Is, but instead a more nuanced approach, designed to reflect the multiplicity of uses we actually encounter. At §65 his imagined interlocutor objects on this very basis, and §66 begins Wittgenstein’s response with his account of games, which, he argues, do not have a common essence but are instead to be thought of as manifesting a “family resemblance,” and which account leads directly into the question addressed at §89; the point being that the discussion of names here is central to the main argument of the entire book.

We’ll have much more about that in a coming post, but let’s get back to names in particular. Names are often thought to manifest the quintessence of linguistic meaning in their purity: they mean simply “that guy” (or thing), and then the theoretical task (as in Kripke) is to see how the meanings of more complex linguistic items can be assimilated to this archetypal case. And names do indeed point to particular people or things (that part is right). But that’s not all they do, and even when they do, how they do it is often a much subtler phenomenon than “—> that guy there.” As we’ve seen, especially in the cases of deliberate coinage or change, they – or, rather, their various uses – express attitudes, and even, as Elliot Page’s own statement on the matter makes clear, attempt to bring about corresponding changes in the world. Bare signposts don’t do that.