by Brooks Riley

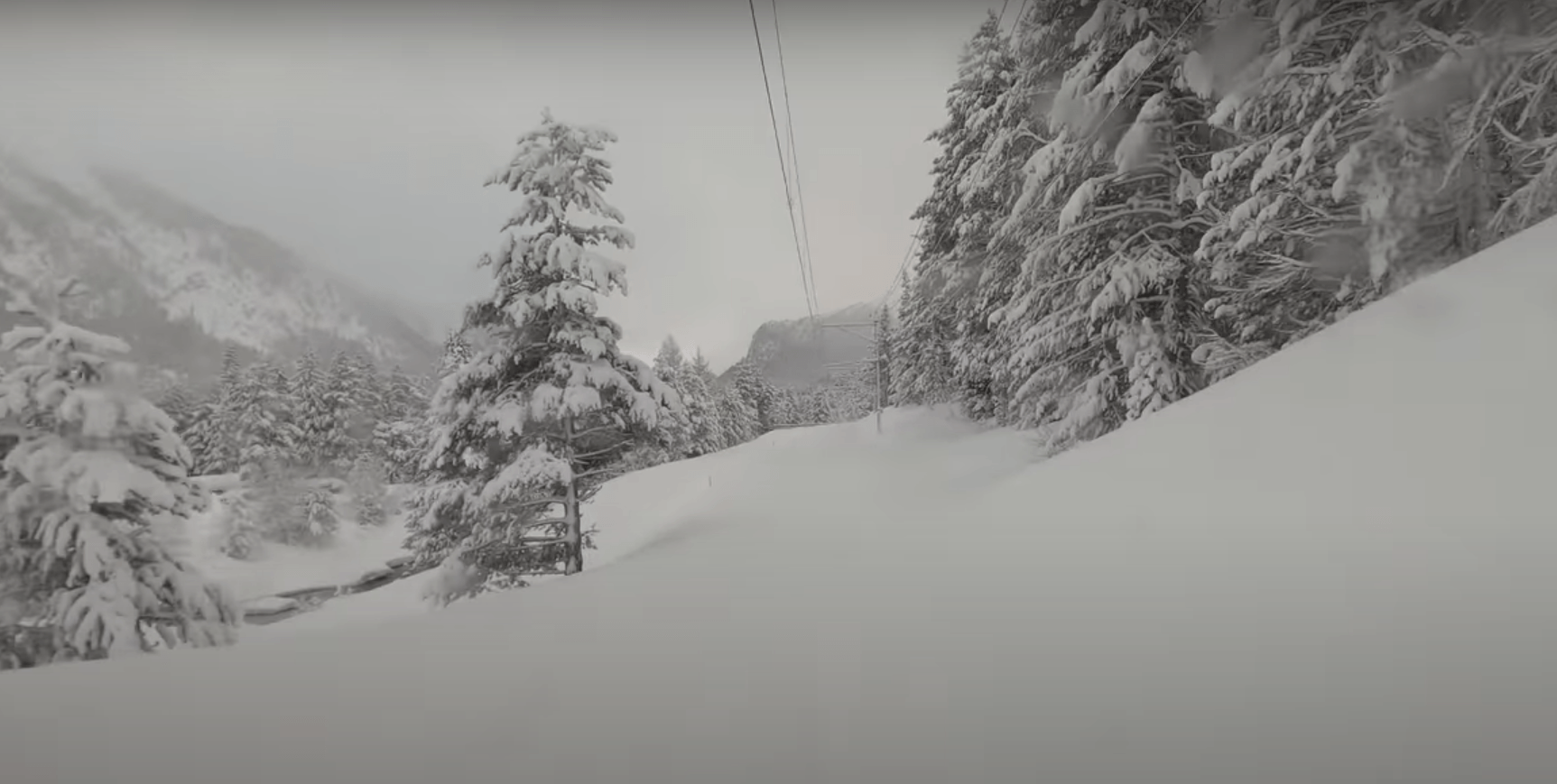

Of all the secondary discomforts imposed by the pandemic, the most treacherous may be inertia. Life, interrupted, can be characterized as an absence of movement, like a stream that stops running, stagnating as the surface begins to cloud with algae and other still-standing detritus. Inertia that stems from the current situation can quelch any creative impulse. Even cinema, that paradigm of life in motion—the moving picture—isn’t much help if we expect our own lives to keep moving as well as movies do. They don’t, at least not right now.

Of all the secondary discomforts imposed by the pandemic, the most treacherous may be inertia. Life, interrupted, can be characterized as an absence of movement, like a stream that stops running, stagnating as the surface begins to cloud with algae and other still-standing detritus. Inertia that stems from the current situation can quelch any creative impulse. Even cinema, that paradigm of life in motion—the moving picture—isn’t much help if we expect our own lives to keep moving as well as movies do. They don’t, at least not right now.

Now we sit at home and consume an ersatz elixir of motion on our streaming platforms, and without quite realizing it, get our kinetic gratification by surfing a narrative, instead of going out for a drive or a walk and seeing our visual field alter naturally.

Movement in this case is not about physical activity, or what we do, but rather about what we see, the perception of changing location in one or another direction—forward, out, away, off, back. On a walk, we may be thinking about our muscles, or about the surrounding nature. But we are mostly oblivious to the subtle changes in our field of vision as we move forward—that constant progress of our steps which alters the panorama ever so slightly. Seen this way, movement feeds our perceptions at the instinctual level. This is where the brain boards a train, metaphorically, to exercise its ability to adjust to change.

I miss trains. I miss the way the scene outside the window rapidly evolves as the miracle of speed presses ever new images on my retina. I miss the way my mind comes alive and cranks out thoughts and ideas at a similar speed. That there is a connection between what we see and what we think, even if none seems to exist, can be explained this way: Motion embodies two accelerators of thought, energy and change, both of which are in short supply if we’re locked down somewhere. The more sedentary and static our lives become the more we depend on the illusion of motion provided by second-hand sources. As the pandemic wears on, I find myself spending less time reading and more time on YouTube, not chasing stories to get lost in, but seeking some kind of eye candy that moves. Read more »

In many ways, the story of my life is the story of books that I have read and loved. Books haven’t just shaped and dictated what I know and think about the world but they have been an emotional anchor, as rock solid as a real ship’s anchor in stormy seas. As the son of two professors with a voracious appetite for reading, it was entirely unsurprising that I acquired a love of reading and knowledge very early on. The Indian city of Pune that I grew up in was sometimes referred to as the “Oxford of the East” for its emphasis on education, museums and libraries, so a love of learning came easy when you grew up there. For 35 years until their mandatory retirement, my parents both taught at Fergusson College in Pune.

In many ways, the story of my life is the story of books that I have read and loved. Books haven’t just shaped and dictated what I know and think about the world but they have been an emotional anchor, as rock solid as a real ship’s anchor in stormy seas. As the son of two professors with a voracious appetite for reading, it was entirely unsurprising that I acquired a love of reading and knowledge very early on. The Indian city of Pune that I grew up in was sometimes referred to as the “Oxford of the East” for its emphasis on education, museums and libraries, so a love of learning came easy when you grew up there. For 35 years until their mandatory retirement, my parents both taught at Fergusson College in Pune.

At the 100th anniversary of John Rawls’ birth back in February, some of the most generous op-eds, whilst celebrating the brilliance of his thought, lamented the torpor of his impact. ‘Rawls studies’ are by no means the totality of political philosophy, but they are one of its most significant strands, and his approach has been dominant for the past 50 years. I’m an admirer of political philosophy, having happily spent much time and energy studying it, specifically looking at theories of deliberative democracy, an area with important connections to Rawls’ thought. That political philosophy does not have much to say that is of direct practical concern does not bother me, the sense that it is not just uninfluential, but is disconnected from the reality of the present moment does though.

At the 100th anniversary of John Rawls’ birth back in February, some of the most generous op-eds, whilst celebrating the brilliance of his thought, lamented the torpor of his impact. ‘Rawls studies’ are by no means the totality of political philosophy, but they are one of its most significant strands, and his approach has been dominant for the past 50 years. I’m an admirer of political philosophy, having happily spent much time and energy studying it, specifically looking at theories of deliberative democracy, an area with important connections to Rawls’ thought. That political philosophy does not have much to say that is of direct practical concern does not bother me, the sense that it is not just uninfluential, but is disconnected from the reality of the present moment does though. Anderson Ambroise. Rubble Sculpture.

Anderson Ambroise. Rubble Sculpture.

I don’t think I saw an actual daffodil until I was 19, although I had admired the many varieties I saw pictured in bulb catalogs and even—I hesitate to admit this—written haiku about daffodils (at 14, in an English class). When my first husband and I drove through Independence, Missouri, early in our marriage, I saw my first daffodils, a large clump tossing their heads in a sunshiny breeze. Wordsworth flashed upon my inner ear, and as I remember it, I recited “And then my heart with pleasure fills, and dances with the daffodils!” (If I did in fact say that, I’m sure I added the gratuitous exclamation point.) My husband, who was driving, gently asked me to return my attention to the map (I was navigating).

I don’t think I saw an actual daffodil until I was 19, although I had admired the many varieties I saw pictured in bulb catalogs and even—I hesitate to admit this—written haiku about daffodils (at 14, in an English class). When my first husband and I drove through Independence, Missouri, early in our marriage, I saw my first daffodils, a large clump tossing their heads in a sunshiny breeze. Wordsworth flashed upon my inner ear, and as I remember it, I recited “And then my heart with pleasure fills, and dances with the daffodils!” (If I did in fact say that, I’m sure I added the gratuitous exclamation point.) My husband, who was driving, gently asked me to return my attention to the map (I was navigating).

In 1887 Ludwik Zamenhof, a Polish ophthalmologist and amateur linguist, published in Warsaw a small volume entitled Unua Libro. Its aim was to introduce his newly invented language, in which ‘Unua Libro’ means ‘First Book.’ Zamenhof used the pseudonym ‘Doktor Esperanto’ and the language took its name from this word, which means ‘one who hopes.’ The picture shows Zamenhof (front row) at the First International Esperanto Congress in Boulogne in 1905.

In 1887 Ludwik Zamenhof, a Polish ophthalmologist and amateur linguist, published in Warsaw a small volume entitled Unua Libro. Its aim was to introduce his newly invented language, in which ‘Unua Libro’ means ‘First Book.’ Zamenhof used the pseudonym ‘Doktor Esperanto’ and the language took its name from this word, which means ‘one who hopes.’ The picture shows Zamenhof (front row) at the First International Esperanto Congress in Boulogne in 1905.

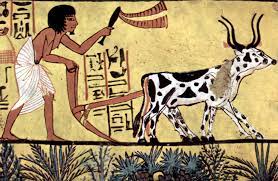

If, for a long time now, you’ve been getting up early in the morning, setting off to school or your workplace, getting there at the required time, spending the day performing your assigned tasks (with a few scheduled breaks), going home at the pre-ordained time, spending a few hours doing other things before bedtime, then getting up the next morning to go through the same routine, and doing this most days of the week, most weeks of the year, most years of your life, then the working life in its modern form is likely to seem quite natural. But a little knowledge of history or anthropology suffices to prove that it ain’t necessarily so.

If, for a long time now, you’ve been getting up early in the morning, setting off to school or your workplace, getting there at the required time, spending the day performing your assigned tasks (with a few scheduled breaks), going home at the pre-ordained time, spending a few hours doing other things before bedtime, then getting up the next morning to go through the same routine, and doing this most days of the week, most weeks of the year, most years of your life, then the working life in its modern form is likely to seem quite natural. But a little knowledge of history or anthropology suffices to prove that it ain’t necessarily so.