by Joan Harvey

Nightfall. Outside a low elongated cave entrance a small group of humans sit waiting on stone ledges facing the dark aperture. Kestrels begin to soar close in the late evening sky. Snakes too are gathering below, we’re told, but they aren’t in view. This is Bracken Cave, 20 miles from San Antonio, where 20 million bats, females and their pups, literally hang out. We’ve come from Austin, through miles of pick-up truck dealerships and mini-malls. At first our driver couldn’t find the cave, which is not open to the public, but eventually, guided by people from Bat Conservation International, the nonprofit that owns and protects the cave, we arrived. At dinner we were filled with Texas barbecue and many bat facts, and now everyone is quiet. Waiting. A strong odor permeates the air. Slowly small dark beings emerge, then more and then more, thousands shooting off, darkening the sky. So many they can be seen on radar, and a nearby Air Force base has to shut down each evening as the bats would interfere with flights. We watch the procession very quietly, each feeling in their own way this strange life form that is connected to us and yet so different, familiar and yet unfamiliar, this webbed mammal, this flying thing that has so engaged our imaginations.

Bats are beings who go too high, shooting up into the air — the species from this cave, the Mexican free-tailed bat, can fly at altitudes over 10,000 feet— but also too low, swooping down to face level, or, when they return from their nocturnal hunt, diving like furry missiles into the low entry of the cave to avoid the waiting predators. They’re fast, faster than birds, holding the horizontal speed record at over 160 kilometers (99 miles) per hour. As mammals they’re more closely related to us than birds, and they live almost everywhere we live, yet we rarely see them, and most of us know almost nothing about them. They’re nocturnal, dusty, silent, though when they fly by us in the thousands we can hear a low rush of wings like the rumble of water over rocks.

Bats haunt the urban goth imagination; they flutter out as our inner fears, emerging moonlit from our own projections. We associate bats with the moon, perhaps because in moonlight they are most starkly visible to us. Moonlight and lunacy, bats in the belfry. And of course vampires. Vampire bats were named after the folk character, not the other way round, but in our heads one is associated with the other; for instance, Laurence A. Rickels’s The Vampire Lectures has pictures of a bat skeleton on the cover. But out of a total of more than 1300 bat species there are only three species of vampire bat, and all three are native to South America. Some vampire bats feed on birds and others on livestock; they have infrared sensors and their saliva contains an anticoagulant. They’re also very cooperative, sharing the blood they’ve collected, donor bats initiating contact with starving bats to help them out.

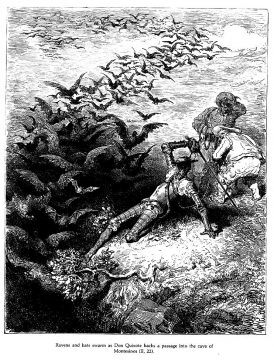

Bats hang upside-down, topsy-turvy, reversed and suspended, blood flowing to the head, the Hanged Man of the Tarot. They live in mysterious caves, dark abodes, leaving at dusk and returning at dawn, liminal times. Associated with witches, they are feminine, fluttery, foreign. I’m told children who have never been exposed to bats fear them, though the newer children’s books give bats their more gentle, friendly due, so perhaps a new generation will grow up with less bat baggage. Watching the swarms of bats emerge from the cave, Gustav Doré’s illustrations from Don Quixote come to mind. Oddly, Whistler is apparently quoted as saying that Doré, who did behave in a somewhat nutty manner, had “bats in his belfry.”

Bracken Cave, where we sat awed and silenced, is the largest known bat colony in the world, and one of the largest concentrations of mammals on earth. It is essentially a bat mega-nursery: 20 million bats give birth to about 20 million pups and then have to feed them all. About 500 pups per square foot cling to the cave walls, and in order to nurse, each bat mom must locate her own pup in the masses of millions every morning when she returns from her nightly hunting expedition. She does this through sound, recognizing her young’s voice in spite of the vocalization of thousands of other hungry babies, and through scent, learned during the first hours after birth when mom and pup nestle together, getting to know each other well. Due to all these warm bat bodies it’s about 104 degrees in the cave, which would otherwise be quite cool. The mother bat has to work hard, consuming nearly her own body weight in insects each night and feeding her baby almost a quarter of her body weight in milk.

Mexican free-tailed bats are also knows as guano bats, and the floor of Bracken Cave is buried under 75 to 100 feet of bat guano built up over centuries of bats dwelling there, not to mention fumes of ammonia and carbon dioxide filling the air. The cave looks innocuous from the outside, but the floor is alive and moving with both guano-eating beetles and six different species of flesh-eating beetles who munch on the unlucky young bats fallen from their roosts. The guano contains thousands of species of bacteria, many of which may live nowhere else and which we know nothing about. Bat guano used to be used as a natural fertilizer and was the largest mineral export of the state of Texas before oil. A glimpse of a recent Halloween baking show on TV showed someone making bat guano out of pistachios.

Bats are astonishingly diverse, making up one-fifth of all mammal species. The more than 1300 species of bats are of the order Chiroptera, from the Greek cheiro meaning hand and ptera meaning wing. Bats used to be classified into two groups, the Megachiroptera and Microchiroptera, but based on genetic analysis, they are now divided into Yinpterochiroptera and Yangochiroptera (appropriately, in Chinese culture bats mean good fortune). Not all bats echolocate, but those who do echolocate at different frequencies and can jam each other’s frequencies. Some moths too are able to detect and jam the bats’ echolocation to evade predation. Unlike birds, bats have teeth. Teeth are some of the densest and heaviest structures of a small vertebrate’s body and bats need a lot of fuel to carry these teeth around with them.

As we watched these thousands of bats emerge for their nightly bug-eating prowl, during which they fly as much as 60 miles out to forage and collectively eat up to 147 tons of insects a night, I was reminded of Thomas Nagel’s justly famous paper on consciousness, “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” Nagel argues that consciousness is subjective, so that lacking the organs for echolocation, we could never know what it is like to have the consciousness of a bat. The paper grants bats consciousness and also does not deny the physical basis of consciousness. It speaks to how each of our consciousnesses is subjective, and argues that at least at this stage, an objective view of consciousness is impossible to obtain.

Nagel wrote that when we try to imagine we are bats, we imagine we have very poor vision. But, in fact, many bats have excellent vision, some better than humans. This error does not at all invalidate his paper, but it does show how little we know about the natural world, and how quickly we accept commonly held beliefs. The paper was written in 1974, perhaps before it was more commonly known that many bats can actually see quite well. Some have very large eyes and use no echolocation, and even those that do echolocate can see. Interestingly, according to Wiki, in his argument against Nagel, Daniel Dennett denies Nagel’s claim that the bat’s consciousness is inaccessible, contending that any “interesting or theoretically important features of a bat’s consciousness would be amenable to third-person observation. For instance, it is clear that bats cannot detect objects more than a few meters away because echolocation has a limited range.” But in actuality, bats can use echolocation for a range of up to 20 meters, which is more than a few. This is perhaps nitpicking on my part, and does not affect the general gist of either argument, but it is interesting that two renowned thinkers both get bats a little bit wrong.

Dennett is reluctant to attribute consciousness to any animal without proof, saying we can be agnostic about what it is like to be a grizzly bear, and that thinking a bear is conscious might just be an overworking of our imagination. “[I]t is common and natural to impute more understanding to an organism than it actually has.” Natural selection is mindless, he says, and we don’t yet know whether beings other than human have any comprehension of what they do.

I happened during this trip to Texas to be reading anthropologist Eduardo Kohn’s book, How Forests Think, about Kohn’s time with the Runa people in Ecuador. Kohn too mentions Nagel, but takes it in the opposite direction from Dennett. Kohn gives selfhood to all living things: “A self then, whether ‘skin-bound’ or more distributed, is the locus of what we can call agency.” Selves think, but not necessarily in the time scale we’re used to. “Biological lineages also think. They too, over the generations, can grow to learn by experience about the world around them…Selves are the product of a specific relational dynamic that involves absence, future, and growth, as well as the ability for confusion.” Thus, we humans are not so completely different from bats that we can have no understanding of what it might be like to be one. Following the thought of Charles Peirce on signs, Kohn concludes that “Because all experiences and all thoughts, for all selves, are semiotically mediated, introspection, human-to-human intersubjectivity, and even trans-species sympathy and communication are not categorically different. They are all sign processes.” The Runa, for example, make scarecrows in the way they imagine a raptor might look like to the pesky parakeets who eat their corn, rather than in a way that looks realistic to humans. And these scarecrows work.

Whether or not we can know what it is like to be a bat, we certainly know how to destroy them. White-nose Syndrome, a fungal disease probably brought to America from Europe by humans, is currently the most famous threat to bats, taking them, as A.E. Stallings wrote, “Into the starless, cold night of extinction.” Many people’s bat houses are not built or placed properly and are actually death traps. Loss of habitat is a big problem, from storms that wipe out trees where bats roost, to loss of caves (to vandalism, human disturbance, or flooding), to real estate development. And, unfortunately, the biggest killer of bats around the world is wind turbines. We’ve learned to site turbines better so that birds don’t fly into them, but bats have different patterns. They run into spinning blades, or the rapid decrease in air pressure around the turbines can cause bleeding in their lungs. Because most bat deaths occur at relatively low wind speeds there is a way to reduce bat deaths by raising the wind speed at which the blades begin to spin, but even though this results in relatively little loss in power generation it has yet to be widely implemented. Bat Conservation International is also working on Ultrasonic Acoustic Deterrents, which would jam the bats’ echolocation or make them uncomfortable around the turbines and keep them from the blades. Scientists got the idea for this from the bat-jamming moths.

Another source of bat habitat loss is, oddly, tequila. With the growth in popularity of tequila, diverse species of wild agave plants are being replaced by cloned agave, and most commercial agave plants are harvested before they flower. But the lesser long-nosed bat and the Mexican long-nosed bat evolved with, and depend on the blossoms of wild agave, and these bats serve as agave’s primary pollinators. Now, with the loss of agave flowers, both species are threatened with extinction and the agave are much less genetically diverse. So some growers now allow 5% of their agaves to flower, providing the nectar that’s essential to the bats’ survival. Growers who do so can designate their products “bat-friendly tequila.” Bat-friendly brands include Tequila Ocho, Tapatio, Siete Leguas, Tesoro de Don Felipe and Siembra Valles Ancestral.

Back in Austin the night after Bracken Cave we lined up with hundreds of other people on and below the Congress Avenue Bridge to watch the much smaller number of bats emerge. Bat tourism brings in 14 million dollars a year to Austin. When I returned home to Colorado, conveniently waiting for me in the latest New York Review of Books was an article about Texas by Annette Gordon-Reed, descendant of a slave brought to East Texas in the 1850s. Gordon-Reed describes how most of us know Texas as the western cattle and oil state, rather than, as much of it was and is, an extension of the South. I personally only learned of the Texas cotton fields through the Bracken Cave bats, who save the region’s cotton growers an estimated $741,000 every year in pesticide and crop damage costs. Gordon-Reed tells us that Austin was named after Stephen F. Austin, a pro-slavery colonizer of Mexico, and son of an enslaver, who finally changed his mind about the institution because he worried that if slavery was continued the number of blacks might equal or outnumber the whites and kill them or have sex with white women. I hadn’t known the city of Austin was named for this man, the “Father of Texas,” and I wonder how many of the happy drunken people listening to music or scootering around or just living in this unusually liberal piece of the state had any awareness of this history.

Which is to say, in both the natural world and our human one there are always many connections and always much to learn.

**************

If you want to visit Bracken Cave you can join Bat Conservation International and go on a tour with them. Or you can join them just to support bats, and get their Bat magazine.

Daniel Dennett, From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds, 2017

Annette Gordon-Reed, “The Real Texas,” The New York Review of Books, October 24, 2019

Eduardo Kohn, How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human, 2013

Thomas Nagel, “What Is It Like to be a Bat?” 1974