by Akim Reinhardt

^

Royalty

Aristocracy

Church Officials

The Merchant Class

Skilled Crafts Workers

The Goddamned Peasants

The Unbelieving Under Class

Criminals to Be Caged & Tortured

Those Whom We Will Publicly Execute

^

WASPS

White Catholics

White-Skinned Jews

Model Minority Asians

White-Skinned, Anglo-Latinx

American Indians as they are Imagined

Dark-Skinned Hispanic Latinos and Latinas

American Indians in Real Life, Not Your Fantasies

African or Indigenous Americans, Depending Where You Are

^

Hahvahd

Harvard and Yale

Princeton, Cornell, Columbia

The Other three Ivy League Schools

Other Elite Private Colleges/Universities

A Small Number of Elite Public Universities

United States’ Elite Military Academy Universities

Flagship Public Research Universities in Most U.S. States

Second Class Public Research Universities across the United States

Former Teacher’s Colleges and Other Underfunded Public Universities

Real Colleges You Have not Heard of and Think, Huh, Is That a Real College?

^

University

4-Year Colleges

Community Colleges

Accredited Online Colleges

Sham, For-Profit Online Colleges

Secondary Schools (aka High Schools)

Middle Schools (aka Junior High Schools)

Primary Schools (aka Elementary or Grade schools)

Daycare Single Mom Sends Child to While Studying for GED

^

Profs

Associate Profs

Untenured Assistant Profs

1-Year Visiting Assistant Professors

Lecturers on Renewable 1-Year Contract

Long Term Adjuncts Who Keep Showing Up

Grad Students with New Syllabi and Fragile Dreams

Come-and-Go Adjuncts Juggling 6 Classes at three Schools

Politician Who Teaches PoliSci Class & Votes to Slash Ed Funding

^

The PhDs

The Medical Degrees

Law/Engineering Degrees

Other Hip Professional Degrees

Various Master of Sciences Degrees

Various Master of Art/Philosophy Degrees

Bachelor of Science Four Year College Degrees

Bachelor of Arts Four Year Degrees: Social Sciences

Bachelor’s of Arts Four Year Degrees in the Humanities

Associate of Arts Degree from a 2 year Community College

M.A., B.A., or A.A. Degrees from an Accredited Online Colleges

Four Year High School Degrees from Expensive Private High Schools

Four Year High School Degrees from Very Selective Public High Schools

Four Year High School Degrees from Open Admissions Public High Schools

General Equivalency Diplomas Earned Taking an Exam Instead of enduring HS

^

3QD Readers

Elite Mag Readers

NYT/WaPo/WSJ Readers

Tabloid Newspaper Readers

People Magazine and SI Readers

Facebook and Twitter Doom Scrollers

Young Adult Fantasy/Sci Fi Book Readers

Small Children Reading Cute Children’s Books

Readers of Graffiti on Doors of Bar Bathroom Stalls

^

Activists

Honest Critics

The Numb Underclass

The Blind Underclass Strivers

Paranoid, Neurotic Middle Classes

Justifiers, Rationalizers, & Excuse Makers

People Who Embrace, Profit from these Pyramids

Precious Children of Embracers & Profiteers of Pyramids

Parents, Furiously Indignant I Dared Slight their Precious Children

Me, Despite My Money & Credentials, Skulking Down Here Like I Belong

^

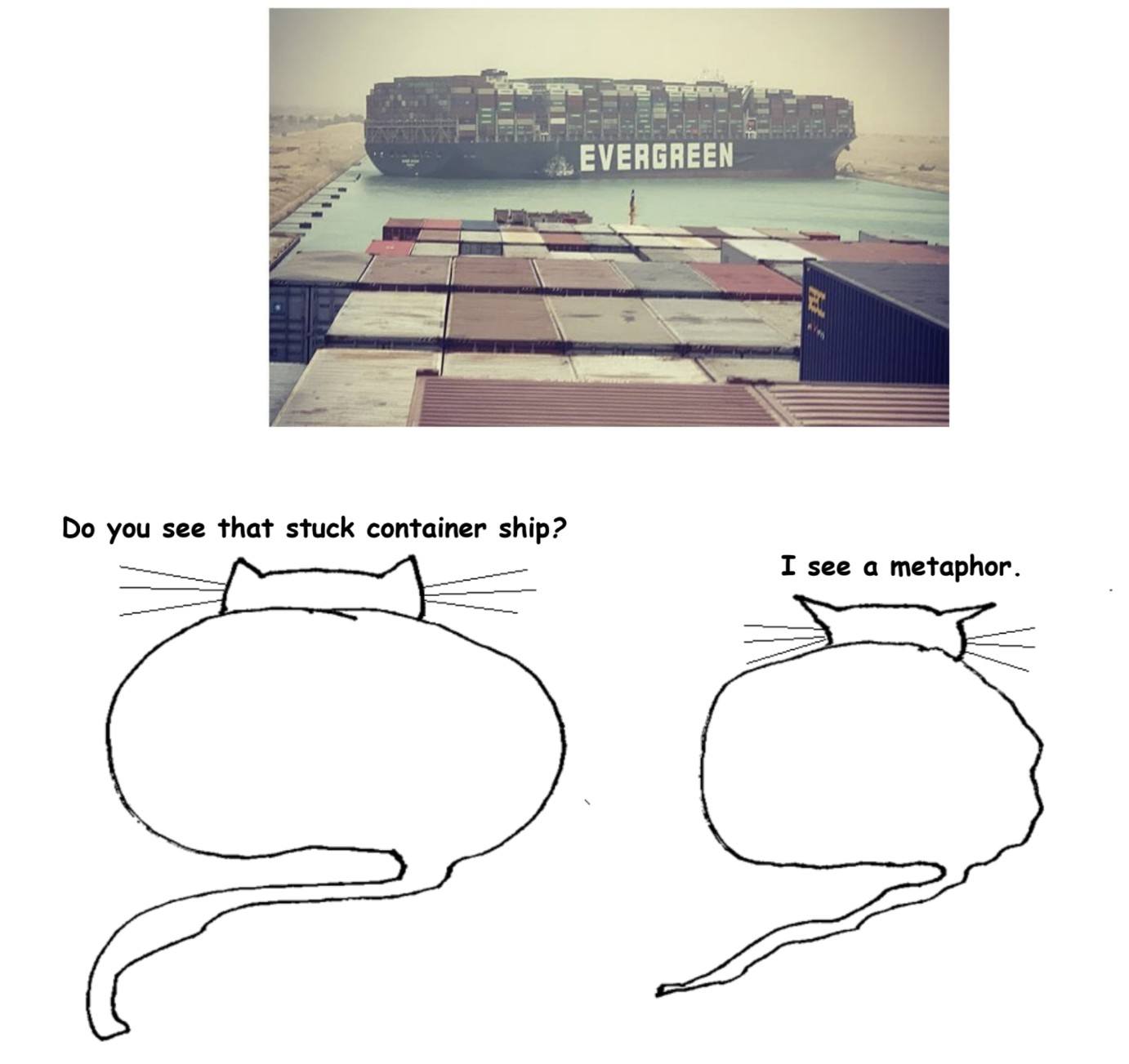

I

Us

You

Them

All of ‘Em

Eight Billion

Or Thereabouts

And Still Counting

The World’s Many Souls

Drifting and Stumbling About

Each 1 a Human Stone Slotted into

Pyramids of Social, Cultural, Economic

Ranking, Status, Power, Privileges, Opportunity

Perhaps Knowing, or Not, That They Are Very likely

Stuck in Those Slots, More or Less, for All of Their Days

Wallowing in Resentment or Finding a Way to Look Past It

Because At Least They Can Write their Name in Capital Letters

akimreinhardt’s

website is the

publicprof

essor.

com

.

I discovered my ideal radio station by accident.

I discovered my ideal radio station by accident.

I’ll return to that second crack once we’ve explored the first one. But why do that at all? Does free will matter to anyone but a couple of bickering philosophers? Of course it does! Sam Harris noted in his recent

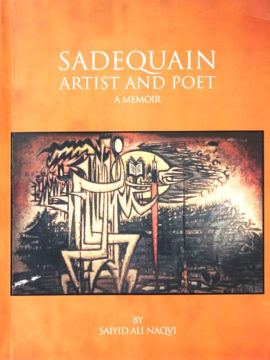

I’ll return to that second crack once we’ve explored the first one. But why do that at all? Does free will matter to anyone but a couple of bickering philosophers? Of course it does! Sam Harris noted in his recent  “Sadequain!” The very name is like a magic word that triggers a tumult of images in the mind. Arguably, no Pakistani artist has elicited more admiration, evoked more passion, and received more adulation than Saiyid Sadquain Ahmad Naqvi, the subject – and really, the hero – of the book “Sadequain: Artist and Poet – A Memoir” by Saiyid Ali Naqvi. In the world of art, be it painting, music, or literature, it is the pinnacle of achievement to be recognized by a single name – to need no further introduction. And rare indeed is the artist who achieves this distinction in his or her own life, as Sadequain did remarkably early in his career as an artist. And this delightful, beautiful, and insightful book shows why. Beginning with the earliest and formative years of Sadequain when he was not yet a legend, it takes the reader systematically through all stages of his life and his growth as an artist, laying bare both the immense determination and the perpetual restlessness of the artist’s genius.

“Sadequain!” The very name is like a magic word that triggers a tumult of images in the mind. Arguably, no Pakistani artist has elicited more admiration, evoked more passion, and received more adulation than Saiyid Sadquain Ahmad Naqvi, the subject – and really, the hero – of the book “Sadequain: Artist and Poet – A Memoir” by Saiyid Ali Naqvi. In the world of art, be it painting, music, or literature, it is the pinnacle of achievement to be recognized by a single name – to need no further introduction. And rare indeed is the artist who achieves this distinction in his or her own life, as Sadequain did remarkably early in his career as an artist. And this delightful, beautiful, and insightful book shows why. Beginning with the earliest and formative years of Sadequain when he was not yet a legend, it takes the reader systematically through all stages of his life and his growth as an artist, laying bare both the immense determination and the perpetual restlessness of the artist’s genius.

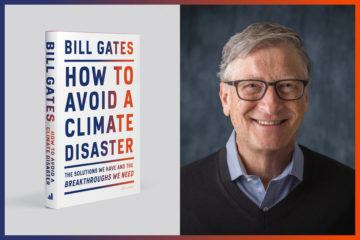

The world we live in is changing, and our politics must change with it. We are in what has been called the ‘anthropocene’: the period in which human activity is threatening the ecosystem on which we all depend. Catastrophic climate change threatens our very survival. Yet our political class seems unable to take the necessary steps to avert it. Add to that the familiar and pressing problems of massive inequality, exploitation, systemic racism and job insecurity due to automation and the relocation of production to cheaper labour markets, and we have a truly global and multidimensional set of problems. It is one that our political masters seem unable to properly confront. Yet confront them they, and we, must. Such is the scale of the problem, the political order needs wholesale change, rather than the small, incremental reforms we have been taught are all that are practicable or desirable. And change, whether we like it or not is coming anyway: between authoritarian national conservative regimes, which with all the inequality, xenophobia, or that of a democratic, green post-capitalism. The thing that won’t survive is liberalism.

The world we live in is changing, and our politics must change with it. We are in what has been called the ‘anthropocene’: the period in which human activity is threatening the ecosystem on which we all depend. Catastrophic climate change threatens our very survival. Yet our political class seems unable to take the necessary steps to avert it. Add to that the familiar and pressing problems of massive inequality, exploitation, systemic racism and job insecurity due to automation and the relocation of production to cheaper labour markets, and we have a truly global and multidimensional set of problems. It is one that our political masters seem unable to properly confront. Yet confront them they, and we, must. Such is the scale of the problem, the political order needs wholesale change, rather than the small, incremental reforms we have been taught are all that are practicable or desirable. And change, whether we like it or not is coming anyway: between authoritarian national conservative regimes, which with all the inequality, xenophobia, or that of a democratic, green post-capitalism. The thing that won’t survive is liberalism.