by Adele A. Wilby

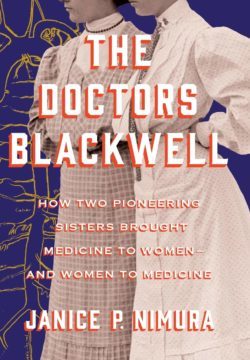

Over recent times, many books have been published with the aim of writing women into history and crediting them for the achievements they have made to the benefit of humanity more broadly. Janice P. Nimura’s The Doctors Blackwell is in that genre of women’s history and she effectively narrates the biographies of the first two remarkable women to study and practice medicine in the United States: Elizabeth Blackwell and her younger sister, Emily.

Over recent times, many books have been published with the aim of writing women into history and crediting them for the achievements they have made to the benefit of humanity more broadly. Janice P. Nimura’s The Doctors Blackwell is in that genre of women’s history and she effectively narrates the biographies of the first two remarkable women to study and practice medicine in the United States: Elizabeth Blackwell and her younger sister, Emily.

In this modern world where the sky is literally the limit for women should they have the ambition, determination and the opportunity, it is sometimes difficult to think of them being stifled in such a way as to constrain their potential, yet that has been the plight of women throughout history, and indeed remains the situation for many women across the globe. Gender has been a crucial factor in defining the lives of women, probably exacting a terrible toll of lifelong intellectual frustration and stifling ambition for many of them. As Nimura’s book reveals, Elizabeth Blackwell, a ‘solitary, bookish, uncompromising high-minded’ young woman was one such woman, until she found her way into medicine. Read more »

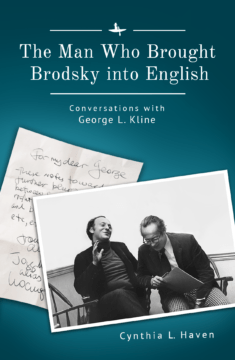

Cynthia, let me begin by asking you to describe your path to the book—a double path that led you to Joseph Brodsky and to George L. Kline.

Cynthia, let me begin by asking you to describe your path to the book—a double path that led you to Joseph Brodsky and to George L. Kline.

Philosophy of science, in its early days, dedicated itself to justifying the ways of Science to Man. One might think this was a strange task to set for itself, for it is not as if in the early and middle 20th century there was widespread doubt about the validity of science. True, science had become deeply weird, with Einstein’s relativity and quantum mechanics. And true, there was irrationalism aplenty, culminating in two world wars and the invention of TV dinners. But societies around the world generally did not hold science in ill repute. If anything, technologically advanced cultures celebrated better imaginary futures through the steady march of scientific progress.

Philosophy of science, in its early days, dedicated itself to justifying the ways of Science to Man. One might think this was a strange task to set for itself, for it is not as if in the early and middle 20th century there was widespread doubt about the validity of science. True, science had become deeply weird, with Einstein’s relativity and quantum mechanics. And true, there was irrationalism aplenty, culminating in two world wars and the invention of TV dinners. But societies around the world generally did not hold science in ill repute. If anything, technologically advanced cultures celebrated better imaginary futures through the steady march of scientific progress.

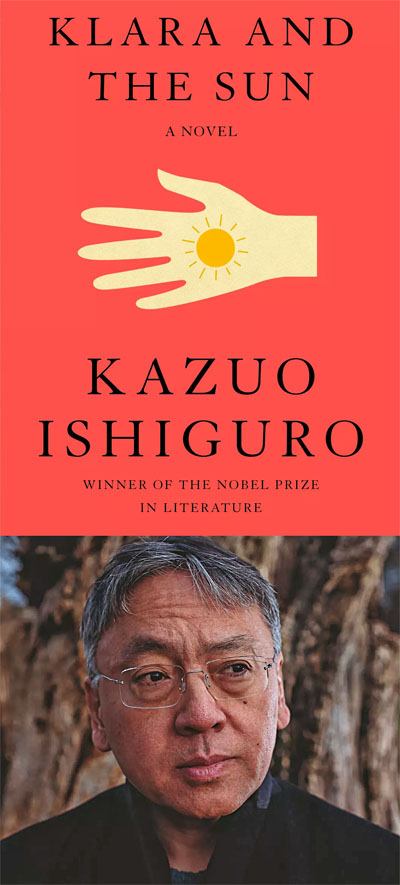

For some time, Sir Kazuo Ishiguro has been slyly replacing Dame Iris Murdoch as the author to whom I most regularly return. His enchanting and disturbing new novel, Klara and the Sun, his first since winning the 2017 Nobel Prize, is unlikely to diminish this trend. I wrote in a

For some time, Sir Kazuo Ishiguro has been slyly replacing Dame Iris Murdoch as the author to whom I most regularly return. His enchanting and disturbing new novel, Klara and the Sun, his first since winning the 2017 Nobel Prize, is unlikely to diminish this trend. I wrote in a  have instrumental value. That is, the value of given technology lies in the various ways in which we can use it, no more, and no less. For example, the value of a hammer lies in our ability to make use of it to hit nails into things. Cars are valuable insofar as we can use them to get from A to B with the bare minimum of physical exertion. This way of viewing technology has immense intuitive appeal, but I think it is ultimately unconvincing. More specifically, I want to argue that technological artifacts are capable of embodying value. Some argue that this value is to be accounted for in terms of the

have instrumental value. That is, the value of given technology lies in the various ways in which we can use it, no more, and no less. For example, the value of a hammer lies in our ability to make use of it to hit nails into things. Cars are valuable insofar as we can use them to get from A to B with the bare minimum of physical exertion. This way of viewing technology has immense intuitive appeal, but I think it is ultimately unconvincing. More specifically, I want to argue that technological artifacts are capable of embodying value. Some argue that this value is to be accounted for in terms of the

We think of AI as the stuff of science, but AIs are born artists. Those artistic talents are the key to their scientific power and their limitations.

We think of AI as the stuff of science, but AIs are born artists. Those artistic talents are the key to their scientific power and their limitations.