by Thomas O’Dwyer

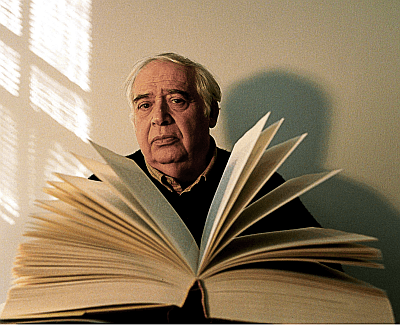

The outpouring of words after the passing of literary critic Harold Bloom on October 14th was astonishing. Who knew that an 89-year-old American academic who still muttered about things like great literary canons and dead white male Victorian-era poets could cause such a ripple in self-absorbed 21st-century space-time? However, the eulogies, obituaries, and memoirs haven’t all been launched on a sea of love and regret. They seem equally divided between affection and snark. Most of the vinegar appears to drip out of academia, or what’s left of the battered and deconstructed humanities departments where Bloom made his name in those bygone days when literary snobs looked down their noses at such vulgar faculties as science, computers and (ugh!) business studies.

It’s no surprise that the academic journals and commentators are so sniffy. When one of the tenured pack moves from writing papers that are read by five people to producing books that top the bestseller lists, the green rot of envy and disapproval spreads like bindweed. One professor commented in an article, “Lest we forget, Bloom was also a bad scholar. His Shakespeare book is written horribly and says nothing.” Meow!

“He’s a wandering Jewish scholar from the first century,” Cambridge Professor Sir Frank Kermode, the English literary critic, once wrote of Bloom. “There’s always a pack of people sitting around him to see if any bread or fishes are going to be handed out. And I think there is in him a lurking sense that when the true messiah comes, he will be very like Harold.” Kermode was once labelled “distinguished;” now he too is merely deceased and forgotten.

It’s not only humanities professors – the late physicist Stephen Hawking was regularly scorned by his peers from the day A Brief History of Time hit the pop charts. It was as if his physicist’s brain had lost ten IQ points merely by addressing the hoi polloi who bought paperbacks. Forming your bubble outside the tenured bubble inevitably invites pinpricks.

Harold Bloom, a son of immigrants from Odessa, was raised as an Orthodox Jew in a Yiddish-speaking household, where he learned Hebrew. He learned English at the age of six. He discovered Hart Crane’s Collected Poems, which inspired his fascination with poetry. After studying at Yale, he joined the English Department there from 1955 and stayed to 2019, teaching his final class four days before his death. He received a MacArthur Fellowship in 1985.

But there are bubbles within bubbles, and it is doubtful that many people beyond the readership of the weighty newspapers and magazines or literary websites have spared many thoughts for the passing of Harold Bloom. The era and milieu from which he came have long since gone, and his books might now be as relevant as spats. However, the British Telegraph newspaper for one used the word “colossus” in its headline for Bloom’s obituary. It followed up:

A colossal figure in American academic life in every sense, Bloom was impossible to ignore. He claimed, probably correctly, to be the best-read man in America (he once said he could consume books at a rate of 1,000 pages an hour). His comfortable familiarity with the canon of Western literature was extraordinary.

Fine, but why should anybody care? Even to pose such a question would horrify Harold Bloom because it might suggest what he had long suspected – that his life’s work promoting the vital importance of Western literature might have been in vain. “There is no single way to read well, though there is a prime reason why we should read. We read not only because we cannot know enough people, but because friendship is so vulnerable, so likely to diminish or disappear, overcome by space-time, imperfect sympathies and all the sorrows of familial and passing life.” (How to Read and Why, 2000).

Bloom wrote extensively on William Shakespeare, W.B. Yeats, James Joyce, Samuel Becket and all the 26 writers he chose to represent Western literature in his most famous popular book The Western Canon. Before his bid to win a mass audience soured his name in academia, Bloom earned professional plaudits for the Anxiety of Influence, published in 1973. It not only gave a new phrase to the language but has generated its anxieties and influences ever since.

His concept of the anxiety of influence may outlive the name of Bloom himself. In the book, he argued that creativity was not a grateful bow to the past, but a clash of Titans. New developing artists deny and distort their literary ancestors while producing work that reveals an inescapable debt to them. You kill your parents and then pass on their DNA. The idea has slipped into popular culture – one rapper said he suffered from the agony of being influential and there’s a Canadian band named Anxiety of Influence.

Having entered the easily-irritated world of general readership, Bloom did not shy away from controversy. He took on political correctness, feminists, multiculturalists, Marxists, neoconservatives, and other ideologies of postmodern dispute. His sharp and learned opinions had him condemned as a reactionary, a misogynist and a dinosaur. He was also praised as a progressive, visionary and lover of life, art, and people. “I am your true Marxist critic,” he once wrote. “I follow Groucho rather than Karl, and take as my motto Groucho’s grand admonition, ‘Whatever it is, I’m against it.'”

Early in his career, Bloom railed against the classicism of T.S. Eliot – the Romantic poets were his heroes. Over the long decades since, he attacked Afrocentrism, feminism, Marxism. He lumped these and other isms into a category named School of Resentment. He disliked the Harry Potter books, scoffed at Stephen King and said the Nobel Prize awarded to Doris Lessing, author of The Golden Notebook, was political correctness gone mad. While many were in awe of his prolific literary and critical output, it also made him the butt of sly jokes. A story once circulated that a graduate student had telephoned him at home with a question. Bloom’s wife answered and said, “I’m sorry, he’s writing a book.” The student replied: “That’s all right. I’ll wait.”

Bloom was a kind and convivial scholar nonetheless, modest about his passion for literature and his prodigious memory. In his later years, he described himself as “a tired, sad, humane old creature.” He was acutely aware that not just his literary criticism, but the “great books” themselves, were becoming ever more irrelevant in the brave new world of visual imagery and instant messaging. He said:

“I always quote – probably over-quote – a great modern American poet (there are also, of course, Mr Frost and if you like him, the abominable Elliott and a few others). It’s the wonderful sentence of Wallace Stevens in prose, ‘Poetry is one of the enlargements of life.’ It’s a very carefully weighted sentence. He is not saying it’s the ultimate enlargement of life or the only enlargement of life but it is one of the enlargements. I think I’m willing to go by that. It doesn’t, of course, mean enlargement in the sense of taking a photograph and enlarging it. He means something rather more inward that I would trust.”

To his last weeks, the frail Bloom continued to teach, give interviews to wandering journalists and patiently answer his students’ phone calls. Aside from the long poems and swathes of books he had memorised, his prodigious memory had a store of literary anecdotes. In an interview with the Irish radio station RTE in 2015, he displayed a passionate affection for the literary contribution the small country had made to “his” canon.

“I used to teach [Ulysses] regularly. I think it’s the greatest of works in English in the 20th century, rivalled only by Proust. But every time I have taught the book I’ve told the students at the beginning we that had to refer to Leopold Bloom as Poldy, lovely fellow that he is his, because his real name was Virago Zarbali, and I object that he has permanently usurped my splendid name of Bloom. But he is wonderful, even though Joyce may not have intended to create this incredibly lovable person. Maybe he did intend it, who knows. Joyce is so diverse and complex.”

Bloom told RTE he was in high school, aged 13 or 14 in New York City, when he found and was fascinated by Ulysses; only by the language, he understood nothing.

“I remember falling in love with that magnificent opening: ‘Stately plump Buck Mulligan…’ and even more a little bit further on, I was swept away by this character based on the real Oliver St. John Gogarty. I got to know him eventually because we drank together at the White Horse Tavern in New York during his long drunken exile. Gogarty was a nasty man, Joyce was quite right about that – a terrible cadger and codger and nudnik in every way. But he did write an excellent book, As I Was Going Down Sackville Street which I enjoyed greatly. But there is a marvellous moment in the Nightown sequence when suddenly, wearing a jesters costume, standing on a pillar or a ladder, the Buck appears, and he cries out as the apparition of Mrs Daedalus rises up. ‘She’s beastly dead, the pity of it; came to kill the dogsbody, the bitchbody. Mulligan meets the afflicted mother, mercurial Malachi.’ Isn’t that wonderful, stunning? My friend [author] Edna O’Brien and I have chanted that a lot to one another. I miss Edna, she’s so beautiful. Does she still always wear a rose? I was always falling in love with her, every time I’ve seen Edna. If she hears this broadcast, beautiful creature, allow me to send you my love. Such a person, in every way, and a great short story writer. She’s a fascinating novelist but (I figure, she mightn’t like my saying this) I like her stories even better. ”

“Ah yes, there is also the divine Oscar [Wilde]. He is marvellous. I sometimes think that except for my hero Sir John Falstaff, post-Shakespeare anyway, the person I like best is Lady Augusta Bracknell. Of all the brilliant things she says, I like best what was at the end: ‘Come, Gwendolyn, we have missed five or six trains already. To miss any more might expose us to comment upon the platform.’ The sublime solipsism of that.”

“The Importance of Being Earnest is a miracle of a play. George Bernard Shaw loathed it. But then Shaw’s the man (magnificent dramatist and mind as he was), who once uttered this incredible sentence, ‘When I consider the mind of William Shakespeare and compare it to my own, I can feel only pity for him.’ He attended the first performance of The Importance and wrote a vicious review of it. We charmers do not love one another. It’s interesting that all the drama post-Shakespeare that matters in English, certainly the stage comedy, was written by the Irish. There’s Wycherly of course, but he’s a rare exception. But Congreve is Irish, and Sheridan and of course Oscar, and Shaw and Sean O’Casey. And Synge, who’s better I think at comedy that he is in the dark vision. It’s an astonishing panoply. ”

Bloom added that the four greatest writers of the 20th century, leaving aside poets, were James Joyce, Marcel Proust, Franz Kafka and Samuel Beckett. “Beckett I actually knew in New York City and also in Paris, the most humane and gentle and humorous and charming person imaginable. He lasted a long time, Becket, into his 80s. Unassuming, very gentle, a curiously lyrical personality. I spent some time in various bars in Paris when we talked. He could drink a fair amount, but then in those days, I could also, being much younger. He could be quite forceful, though. He had what Dr. Johnson praises as the faculty or ability to transform opinion into knowledge.”

“To transform opinion into real knowledge. That is as good a criticism of criticism as you could hope to find. … It is wrong to ask either of art or academic life, ‘what is it for?’ It is for itself, and any bending of it to an external purpose will not merely harm it, but destroy it.”