by Martin Butler

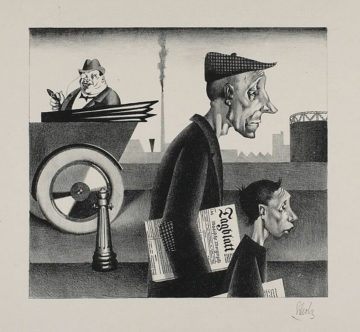

Patriotism is a contested ideal in the culture war which bubbles away in the UK. It’s worth examining not only as an idea in itself but also with regards to how it is understood and expressed in the present cultural context of the UK. It seems to me that the debate is dominated by two ends of a spectrum, both misguided. At one end there are those who find the word itself too problematic to be worth salvaging. It is, they would argue, despite claims to the contrary, unavoidably linked to its ugly cousin, nationalism, with its xenophobic and jingoist associations.[1] On the other end of the spectrum there is a strong pushback against this squeamishness, although this side of the argument, which I call politicised patriotism, tends to associate the sentiment with a narrow set of political views and promotes the cartoonish idea of patriotism focused on flags.

Patriotism is a contested ideal in the culture war which bubbles away in the UK. It’s worth examining not only as an idea in itself but also with regards to how it is understood and expressed in the present cultural context of the UK. It seems to me that the debate is dominated by two ends of a spectrum, both misguided. At one end there are those who find the word itself too problematic to be worth salvaging. It is, they would argue, despite claims to the contrary, unavoidably linked to its ugly cousin, nationalism, with its xenophobic and jingoist associations.[1] On the other end of the spectrum there is a strong pushback against this squeamishness, although this side of the argument, which I call politicised patriotism, tends to associate the sentiment with a narrow set of political views and promotes the cartoonish idea of patriotism focused on flags.

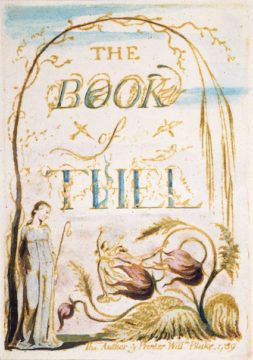

But what is patriotism? Whereas nationalism is the aggressive pushing of your own nation as somehow better than others, patriotism, understood in its benign sense at least, is just love of country.[2] But what exactly does this mean? We need to acknowledge here that, as Benedict Anderson points out, nations are to a large extent ‘imagined communities’.[3] They are constructed entities based on a particular narrative handed down through history and culture. Anderson makes the amusing point that “The Barons who imposed Magna Carta on John Plantagenet did not speak English and had no conception of themselves as “Englishmen”, but they were firmly defined as early patriots in classrooms of the United Kingdom 700 years later.”[4] Anderson, I think, would want to contrast an imagined community with communities of individuals who in some way have direct social interaction. Anthropologist Robin Dunbar famously identified the magic number of 150 as the maximum number of meaningful relationships a human being can maintain.[5] Evidence suggests that hunter-gatherer groups that exceeded this number tended to split. But we use the term ‘community’ in a far broader sense than this, so most communities are indeed ‘imagined’ in Anderson’s sense, and we have no trouble understanding this sense as real community; although we can acknowledge that the word ‘community’ is perhaps often used too loosely.[6] Read more »

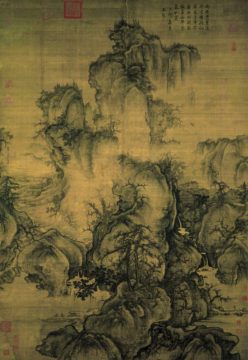

Copse and cosmos

Copse and cosmos

“My first experience home-brewing was before it was legal,” says Jim Koch, cofounder and chairman of Boston Beer Company, maker of Sam Adams. “I did it with my dad. He brought home some yeast … then he brought home some hops, and we made a beer. And I thought it was so cool when the yeast brought the beer to life, and it started to bubble and you got that foam on the top of it, and it had that wonderful bready, ester-y smell, and I was in love.”

“My first experience home-brewing was before it was legal,” says Jim Koch, cofounder and chairman of Boston Beer Company, maker of Sam Adams. “I did it with my dad. He brought home some yeast … then he brought home some hops, and we made a beer. And I thought it was so cool when the yeast brought the beer to life, and it started to bubble and you got that foam on the top of it, and it had that wonderful bready, ester-y smell, and I was in love.” The evidence that pairing music with wine can enhance one’s tasting experience continues to mount since

The evidence that pairing music with wine can enhance one’s tasting experience continues to mount since

Let’s talk about voter suppression. Not about whether it’s good or bad or legal or moral (you can get more than enough of that virtually 24/7), but about what practical implications it might have.

Let’s talk about voter suppression. Not about whether it’s good or bad or legal or moral (you can get more than enough of that virtually 24/7), but about what practical implications it might have.

I discovered my ideal radio station by accident.

I discovered my ideal radio station by accident.