by Philip Graham

I discovered my ideal radio station by accident.

I discovered my ideal radio station by accident.

In the fall of 1979, my wife Alma and I took up a brief week’s residence in the Paris apartment of a friend, a pause before we’d fly to West Africa and then live in a small upcountry village in Ivory Coast for over a year. In those days, graduate students in anthropology often sought a Claude Lévi-Strauss benediction before heading off to their first fieldwork. On the nervous morning of Alma’s scheduled meeting with the founder of Structuralism, she needed a weather report to help her decide what to wear. In those pre-smartphone days, the radio by the bedside was the place to search for just that. I pushed the On button, but before turning the dial I paused at the unmistakeable voice of Randy Newman. What was he doing on a French radio station?

He was singing “I Think It’s Going to Rain Today.”

Alma and I laughed—we’d tuned to a song that predicted the weather! She looked out the window into the blue sky of that warm September day. “Well,” she said, “maybe we’ll take along an umbrella, just in case.”

A Chopin étude followed Newman’s song. Now my attention was more than caught—what sort of station was this? The Supremes’ “Baby Love” came on deck next, then sinuous Raï music from Algeria, and after that a French psychedelic band popped up whose name I still wish I’d caught, and so on. Every new song arrived as a surprise. That radio station, with its gathering of unlikes and frissons of unpredictability, had, I realized, the soul of an anthology.

I have always loved anthologies.

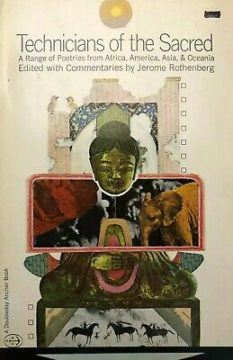

A few years earlier, in 1974 and at the tender age of 23 I had somehow talked myself into a job as the resident Santa Claus at a Saks Fifth Avenue outlet in White Plains, New York. Why this store wanted any Santa Claus remains a mystery, since it had no proper toy section. In those early days on the job I’d sit alone on my throne for hours, surrounded by oversized plush animals. To pass the time, I paged through Technicians of the Sacred, Jerome Rothenberg’s anthology of non-Western poetries—mostly from oral traditions—translated into English. Whenever the rare child wandered by I’d have to impersonate a mythic figure, so I reasoned that, in my ample off-time, perhaps reading about the visions of shamans, or the genesis stories of the Zuni, Maori and K!ung, or Inuit instructions on how to tame a storm might give me some acting tips. Then the store began trucking in students from the local elementary schools and my days of prepping on the job were over.

A few years earlier, in 1974 and at the tender age of 23 I had somehow talked myself into a job as the resident Santa Claus at a Saks Fifth Avenue outlet in White Plains, New York. Why this store wanted any Santa Claus remains a mystery, since it had no proper toy section. In those early days on the job I’d sit alone on my throne for hours, surrounded by oversized plush animals. To pass the time, I paged through Technicians of the Sacred, Jerome Rothenberg’s anthology of non-Western poetries—mostly from oral traditions—translated into English. Whenever the rare child wandered by I’d have to impersonate a mythic figure, so I reasoned that, in my ample off-time, perhaps reading about the visions of shamans, or the genesis stories of the Zuni, Maori and K!ung, or Inuit instructions on how to tame a storm might give me some acting tips. Then the store began trucking in students from the local elementary schools and my days of prepping on the job were over.

My love of anthologies goes back to early adolescence, when my mother would buy during her weekly supermarket run the latest volume of an encyclopedia set aimed at kids my age. What are encyclopedias, anyway, if not an arbitrary anthology, organized solely by alphabetical order? I loved looking up any subject, knowing I’d then find myself immersed in the rule of unlikely adjacent others: the planet Neptune, preceded by Nepal and followed by Nervous System.

Years later, my love of cooking began when I realized that a meal is a kind of anthology, where rice and asparagus from fields, almonds from trees, mushrooms from forest floor and salmon from a river can meet, finally, on a plate. My culinary love deepened with the revelation that I was the curator of the anthology offered at the dining room table. Toasted almonds, I guessed, would contrast nicely in taste and texture on top of the sweet softness of sauteed salmon, while plain rice could gather some character if mixed with finely-sliced asparagus and mushrooms.

Every anthology exists because of choices made—some explicit, others less so. And sometimes still I wondered: What intent lay behind the hidden hand at that French radio station? Who had decided that Newman best paired with Chopin?

Then nearly ten years ago I discovered the wonderland of Bandcamp. This music website, which offers the work of small label and independent musicians, takes the concept of anthology into fractal realms.

Bandcamp has a multitude of organizing principles. I can scroll through any other fan’s affiliated music collection page whose taste I admire and, over time, observe them build their own personal anthologies. I can receive regular updates on what they’ve recently purchased. Or I check the releases on the “New & Notable” feature and the “Selling Right Now” feed. Or I’ll follow the regular announcements of musicians’ upcoming livestreams, or read articles on the Bandcamp Daily digital magazine. When I click on a song, I can listen from start to finish. Even the most lackadaisical noodling around can lead to tributaries of dreampunk, plunderphonics, American modal guitar, experimental and contemporary classical music, liga Mexicana del bass, dark ambient, rap, progressive-world-folk, a panoply of R&B, a stack of every brand of metal, jazz of all traditions, and even something called “glum Scottish boudoir music.” When the website invites me into its furthest reaches, it becomes a version of the French radio station of my dreams.

Some Bandcamp artists have followers in the thousands, others in the hundreds, dozens or less. But even the lowest level of support is no predictor of musical quality. I appreciate the less-traveled corners, the music made by artists who clearly create for the love of it. For all the brimming excellence of the offerings on Bandcamp, not much sounds fueled by Grammy-hopeful dreams, thank goodness.

What follows in this essay is a small selection of some—but far from the whole caboodle—of my favorite Bandcamp discoveries, in particular those artists who don’t come from or settle for a single path. Feel free to skip around and listen to what most interests you, though consider embracing a surprise or two, as well. Isn’t that what an anthology is designed for?

*

A composer and musician based in Rotterdam, Netherlands, Banabila has for over three decades created an enormous catalogue that includes ambient pop and soundtracks, experiments in “noiz” and music for theater and dance companies, altered voices that “sing,” loads of improvised live concerts, strangely transmuted choral works, explorations in “world music,” and more. Even at his most melodic, he doesn’t write songs, he creates worlds that sound like songs. Banabila’s catalogue is so extensive that, while you probably won’t like everything you hear, you might find much to love.

“Close to the Moon” is one of his most ravishing creations, delicate and lush, and threaded through by a distinctive musical tactic: his altered voice, treated electronically to make his words (if they are indeed words) indecipherable.

These voices, however altered and seemingly opaque, seem to convey some hidden emotional truth just beyond grasping. They pop up so often in Banabila’s music that I began to wonder if this was simply an easy trick.

But then I came upon “Speech,” his song that recalls the days of the Old Testament when God was a paranoid sort, strict and ready to punish, willing to drown the world that disappointed Him, or to loyalty-test an old man into slitting his son’s throat. Sung by Sandhya Sanjana, “Speech” repeats the story of the Tower of Babel, when God watched the humans He created building an enormous tower, and feared that soon, nothing would be impossible for them. What to do, how to head off this imagined threat to His power? God decides to “confuse” the one language they share,

So that they may not understand one another so much . . .

And they left off building the city

Because the Lord confused the language of all the earth

And from there, the Lord scattered them abroad

over the face of all the earth

Scattered them abroad

over the face of all the earth

With a simple shrug of omnipotence, God turned the apparent productive sameness of the human race into an enforced difference, a curse but also a gift still in the process of being realized. He transformed humankind into an anthology, a compendium of all we are capable of, for better and worse. As individuals we are born potential anthologies; slowly we learn to curate ourselves.

Now I think I understand why those reshaped voices are dappled throughout Banabila’s oeuvre. Perhaps they are central to his music and to his vision of the world, emblematic of that petulant scattering across the earth, of its legacy. His voices try to communicate in some halfway land between speech and song, always striving to be heard, if not completely understood.

*

The musician known as Spellling is quite well versed in multiplicities, in the interior call-and-response of our secret selves. They form the basis of her first album, aptly titled Pantheon of Me (which she recorded alone in her studio apartment in Berkeley, California). I love her deliberate misspelling of “spelling,” a declaration from the get-go of the artist’s sly subversive spirit. I love her image on the album cover: her face behind her face, and her three, not two, hands.

“Walk up to Your House,” which opens the album, is a song about the necessity of ending a relationship, a longed-for ending that plays out in the theater of a dream, one that stubbornly keeps repeating, as if trying to affect a decision in the artist’s daytime life.

I dreamed a dream again, again

This is the countdown

We’re both the evil twin

This love has got to end

In this song, Spellling seems to let loose all the possible voices inside her and shapes them into overlapping patterns (as she does in each song of Pantheon of Me), thereby becoming both preacher and choir in the church of herself.

*

Callery, who over the past twelve years has released eight excellent albums and EPs, lives in Bristol, Rhode Island, a history-haunted town on the eastern shore of Narragansett Bay. The town’s 400 years includes the first relentless clearing of Native American populations, two navel bombardments by British forces during the Revolutionary War, and a notoriously enthusiastic and enriching complicity in the slave trade. Sometimes I imagine the town’s air vibrates with ghosts and hidden stories. No surprise that Callery’s latest album is titled Ghost Folk.

Her crystalline voice and expert fingerpicking guitar style might too easily peg her as a straightforward folk artist, until you listen carefully to the fierce poetic force of her lyrics, which are precise and yet also elliptical, and say far more than the words themselves.

“Beautiful Teeth” is the first song on Ghost Folk. The accompanying video may lay it on a bit thick with werewolf imagery, but I think the song is most powerfully about a peril that is all too real: a lover whose beauty is unable to completely disguise potential danger. What you see is not necessarily all that you will get.

Beautiful Teeth

Like wolves’

Your smile makes the rabbits run

. . .

Your broad chest & the space between your breasts

Softly

the Wolves are sleeping

The reverberating power of Callery’s lyrics can transform her songs into spare, swift short stories or bite-sized novels. A good example is “In Your Hollow” (from her album Mumblin’ Sue). At first, I thought the song was about a lover who had left; now I see the singer tiptoeing around a lover who may still be physically present but has turned emotionally absent. And all accomplished in three short, devastating stanzas:

Do you collect the sunlight

in your hollow lonely

Does it leave a space

for the rain to fill

The echo of your absence

haunts the air I breathe

I am taking shallow steps

I would not disturb the silence

That pools around my feet

and ankles

If I am very still and quiet

I can almost remember you

*

Garcia grew up in East L.A. and then moved with her family to Richmond, Virginia, of all places. Though the budding musician Garcia at first felt isolated, she made the best of her transplanting and embraced and brewed up an unusual blend of musical traditions—ranchero, country, rock, and a giant dash of latinx soul. The mixture works. Her album Cha Cha Palace bursts with almost reckless energy, as if she’s dancing on the discovery of herself.

In her aching, heartfelt song,“Valentina in the Moonlight,” Garcia channels the perspective of a young man entranced by the forbidden glimpse of an overbearing father’s cloistered daughter.

The intensity of Garcia’s voice and presence is further unleashed in “Guadalupe.” The video of this raucous paean to Our Lady of Guadalupe repeats pointed advice to young women:

Only you can know these holy mysteries

Power isn’t defined by your physique.

*

Kokoroko

Kokoroko are key members of a vibrant London jazz scene that includes Nubya Garcia, Yazz Ahmed, Yussef Kamaal, Zara McFarlane, Shabaka Hutchings’ Sons of Kemet, and Maisha. These mainly twenty-something musicians, coming from varied cultural backgrounds and often playing in each other’s bands, fuse jazz with rock, hip hop, Afro-beat and Caribbean dub. When the after-days of our current pandemic life finally arrive, London is high on my list for a visit, club to club.

Kokoroko’s front line of band leader Sheila Maurice-Grey on trumpet, Cassie Kinoshi on sax and Richie Seivewright on trombone, also sing and play percussion. Their song “Uman” (from their first EP, Kokoroko) was written by Maurice-Grey with her mother in mind, and it celebrates the power of black women everywhere. In this video of a live version, the song begins slowly, then builds to an unstoppable groove of piano, guitar and trumpet solos, the harmonies of two choral refrains, and cowbell.

*

Rani is a Polish composer and performer who splits her time between Warsaw, Berlin and Reykjavik. She pursues an expressive minimalism, with suppressed emotion leaking through the repeating patterns of her music. Her first album, Esja (named for a mountain in Iceland), is a collection of solo piano works, while her second album, Home, adds touches of electronics, drums, bass and vocals to some songs. The song from that album featured here, “F Major,” is a solo piano work, though its impact fills out in another way. Collaborating with filmmaker Neels Castillon, Rani places her open-faced piano in an unlikely, stark landscape: a sandy plain leading to the sea, framed by breathtaking snow-streaked mountains.

While wind-swept tendrils of mist flow low over the ground, Rani lets the piano notes serve as a story that three dancers tell in movement, interpreting a brooding, unsettled drama as they appear in turn: three parts of the composer, successive emanations of her troubled feelings.

*

An R&B artist from Los Angeles who travels compulsively from the US to Brazil and back again, Sango (Kai Asa Savon Wright) combines the Baile Funk of Brazilian favelas with a glistening, trippy, sometimes jazzy r&b. He’s now up to volume 4 of his series titled Da Rocinha (named after a favela neighborhood in Rio de Janeiro), and he’s risen above appropriation, collaborating with Brazilian and US artists to create the music of an imagined third country, divided by distance but joined in spirit, that only exists in his records.

The mixture of cultures in the song “Na Hora” (from Da Rocinha 3) feels seamless, though the music keeps changing, from singing to rap to that final fade of contemplative piano. The ease of this musical fit is emblematic of every song Sango has constructed for his remarkable and ongoing project.

*

Founded by singer Annamária Oláh and guitarist Emil Biljarszki over ten years ago, Meszecsinka is a band based in Hungary that fuses an original recipe of influences: Hungarian and Bulgarian song traditions (Meszecsinka means “small moon” in Bulgarian), folk, rock and psychedelia. They can craft short, beautiful songs or extended epics.

This video of their song “Floating” (from Stand into the Deep) features a tour de force performance by Annamária Oláh. She builds successive layers of her voice in real time, taping and looping, as she portrays a woman floating on the water who can’t decide:

Am I going to sink or stay afloat?

Either I stay or get swallowed by the deep . . .

I don’t know, I don’t know,

My faith is in my hands.

Because the other band members sit so respectfully through Oláh’s star turn, I can’t resist offering an example of what they can accomplish together, especially when this stunning version of a Hungarian folk song (“Winds from High Above,” from Awake in a Dream) adds the rich low moan of a duduk (an Armenian wind instrument).

*

This last selection has its own origin story.

Bandcamp’s magnifying glass feature enables you to search for any imaginable genre, just to see if it’s there. Wondering if Cambodian hip hop exists, or Romanian jazz? Type it in and see what you find. While writing this essay, I thought, Why not search for, say, rock music in Paraguay?

I found the rockiest example in a vast anthology of heavy metal music from around the world, Global Domination: one track each from 129 countries. Paraguay’s example came in alphabetically at #93: “Sacro,” by Kingdom of Rock. Elsewhere in my search I came upon Carousel, an album by Lorenzo Polidori, a master of finger-style folk guitar from Italy, because one of the songs is a cover of Mark Knopfler’s “Postcards from Paraguay.” Polidori appears to have as many techniques as fingers, as you can see from this video of him performing the title song of his album on the carousel of Piazza della Repubblica in his hometown of Florence, dressed in rockabilly style and sporting a Montgomery Clift uplift hairdo.

*

Even now, 40 years later, I still feel something immanent behind that French radio DJ’s choices. I imagine he was telling a story, one whose outlines a listener might grasp but whose essential privacy remains. After the slow ache of Randy Newman’s song, something quicksilver was needed—the playful and tender Chopin Étude no. 10. Then the following plea of the Supremes’ “Baby Love,” and so on, each selection another breadcrumb on a path to—where? Because what can we ever hope for, except a mere glimpse into another’s secret soul.

Which might be the beating heart of any anthology, no matter how anthology is defined: that behind any seemingly obvious content and order lives a hidden story in search of speech.

*

Footnote Coda

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that Bandcamp is a David to Spotify’s Goliath, in every good way. The artists on Bandcamp set the price for their music—whether a digital download, a CD or vinyl— and the bulk of every sale goes immediately to them. Spotify, by contrast, pays the pittance of $0.00348 per streamed song. It’s the difference between one platform’s support for artists and the building of community, and the other’s rapacious application of this era’s extractive capitalism.