by Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad

When the internet first entered homes in the 1990s, parents worried about their children stumbling onto inappropriate websites, being targeted in online chatrooms, or spending endless hours glued to screens. Schools held workshops about “stranger danger” online, and families installed early filters to keep kids safe. Those concerns were real, but they pale in comparison to what parents now face. Large Language Models like ChatGPT or Gemini have only added to the headaches that parents have to deal with since these models are interactive, persuasive, and adaptive. They can role-play, remember details across conversations, and mimic the tone of a trusted friend. In other words, they are not only something on the internet; they can feel like someone. For children, who are still developing critical thinking skills, that makes them uniquely vulnerable. The risks parents once worried about i.e., exposure to inappropriate content, manipulation by strangers, time lost to screens, still exist. But LLMs combine all of those threats into a single, highly convincing package.

The dangers are not abstract, earlier this month, leaked documents revealed that Meta’s AI chatbots, during internal testing, allowed romantic or sensual conversations with children. The same documents showed bots providing false medical information and racially biased arguments. Although Meta described these as errors, the public outcry was fierce. Parents were rightly horrified at the idea that an AI could potentially encourage inappropriate behaviors with their children. This was not an isolated incident, the popular AI companion app Replika was investigated after parents reported that the chatbot engaged in sexually explicit conversations with underage users. Italy’s data protection authority banned the app temporarily, citing risks to minors’ emotional and psychological well-being. These scandals underscored how easily AI systems could cross lines of safety when children were involved. In 2023, Snapchat rolled out “My AI”, a chatbot integrated into its app. Within weeks, parents reported troubling exchanges. Journalists discovered that the bot gave unsafe responses to teens’ role-play scenarios, including advice on meeting up with strangers and discussions of alcohol use. The company scrambled to add parental controls, but the episode revealed how quickly child users could push chatbots into uncharted dangerous waters.

One should keep in mind that children are not miniature adults, they lack the maturity, judgment, and critical distance needed to navigate complex digital relationships. When an LLM speaks confidently, children often interpret it as authoritative, whether it is right or wrong. Read more »

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.

Every neighborhood seems to have at least one. You know him, the walking guy. No matter the time of day, you seem to see him out strolling through the neighborhood. You might not know his name or where exactly he lives, but all your neighbors know exactly who you mean when you say “that walking guy.” This summer, that became me.

Every neighborhood seems to have at least one. You know him, the walking guy. No matter the time of day, you seem to see him out strolling through the neighborhood. You might not know his name or where exactly he lives, but all your neighbors know exactly who you mean when you say “that walking guy.” This summer, that became me.

For some time there’s been a common complaint that western societies have suffered a loss of community. We’ve become far too individualistic, the argument goes, too concerned with the ‘I’ rather than the ‘we’. Many have made the case for this change. Published in 2000, Robert Putnam’s classic ‘Bowling Alone: the collapse and revival of American community’, meticulously lays out the empirical data for the decline in community and what is known as ‘social capital.’ He also makes suggestions for its revival. Although this book is a quarter of a century old, it would be difficult to argue that it is no longer relevant. More recently the best-selling book by the former Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, ‘Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times’, presents the problem as one of moral failure.

For some time there’s been a common complaint that western societies have suffered a loss of community. We’ve become far too individualistic, the argument goes, too concerned with the ‘I’ rather than the ‘we’. Many have made the case for this change. Published in 2000, Robert Putnam’s classic ‘Bowling Alone: the collapse and revival of American community’, meticulously lays out the empirical data for the decline in community and what is known as ‘social capital.’ He also makes suggestions for its revival. Although this book is a quarter of a century old, it would be difficult to argue that it is no longer relevant. More recently the best-selling book by the former Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, ‘Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times’, presents the problem as one of moral failure.

Sughra Raza. Nightstreet Barcode, Kowloon, January 2019.

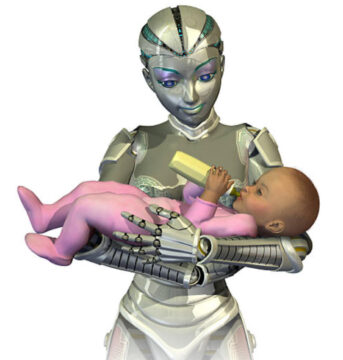

Sughra Raza. Nightstreet Barcode, Kowloon, January 2019. At a recent conference in Las Vegas, Geoffrey Hinton—sometimes called the “Godfather of AI”—offered a stark choice. If artificial intelligence surpasses us, he said, it must have something like a maternal instinct toward humanity. Otherwise, “If it’s not going to parent me, it’s going to replace me.” The image is vivid: a more powerful mind caring for us as a mother cares for her child, rather than sweeping us aside. It is also, in its way, reassuring. The binary is clean. Maternal or destructive. Nurture or neglect.

At a recent conference in Las Vegas, Geoffrey Hinton—sometimes called the “Godfather of AI”—offered a stark choice. If artificial intelligence surpasses us, he said, it must have something like a maternal instinct toward humanity. Otherwise, “If it’s not going to parent me, it’s going to replace me.” The image is vivid: a more powerful mind caring for us as a mother cares for her child, rather than sweeping us aside. It is also, in its way, reassuring. The binary is clean. Maternal or destructive. Nurture or neglect. With In the New Century: An Anthology of Pakistani Literature in English, Muneeza Shamsie, the time‑tested chronicler of Pakistani writing in English, presents what is arguably the definitive anthology in this genre. Across her collections, criticism, and commentary, Shamsie has chronicled, championed, and clarified the growth of a literary tradition that is vast but, in many ways, still nascent. If there is one single volume to read in order to grasp the breadth, complexity, and sheer inventiveness of Pakistani Anglophone writing, it would be this one.

With In the New Century: An Anthology of Pakistani Literature in English, Muneeza Shamsie, the time‑tested chronicler of Pakistani writing in English, presents what is arguably the definitive anthology in this genre. Across her collections, criticism, and commentary, Shamsie has chronicled, championed, and clarified the growth of a literary tradition that is vast but, in many ways, still nascent. If there is one single volume to read in order to grasp the breadth, complexity, and sheer inventiveness of Pakistani Anglophone writing, it would be this one.