by Ashutosh Jogalekar

Two men walking in Princeton, New Jersey on a stuffy day. One shaggy-looking with unkempt hair, avuncular, wearing a hat and suspenders, looking like an old farmer. The other an elfin man, trim, owl-like, also wearing a fedora and a slim white suit, looking like a banker. The elfin man and the shaggy man used to make their way home from work every day. Passersby and motorists would strain their heads to look. Everyone knew who the shaggy man was; almost nobody knew who his elfin companion was. And yet when asked, the shaggy man would say that his own work no longer meant much to him, and the only reason he came to work was to have the privilege of walking home with the elfin man. The shaggy man was Albert Einstein. His walking companion was Kurt Gödel.

What made Gödel, a figure unknown to the public, so revered among his colleagues? The superlatives kept coming. Einstein called him the greatest logician since Aristotle. The legendary mathematician John von Neumann who was his colleague argued for his extraction from fascism-riddled Europe, writing a letter to the director of his institute saying that “Gödel is absolutely irreplaceable; he is the only mathematician about whom I dare make this assertion.” And when I made a pilgrimage to Gödel’s house during a trip to his native Vienna a few years ago, the plaque in front of the house made his claim to posterity clear: “In this house lived from 1930-1937, the great mathematician and logician Kurt Gödel. Here he discovered his famous incompleteness theorem, the most significant mathematical discovery of the twentieth century.”

The reason Gödel drew gasps of awe from colleagues as brilliant as Einstein and von Neumann was because he revealed a seismic fissure in the foundations of that most perfect, rational and crystal-clear of all creations – mathematics. Of all the fields of human inquiry, mathematics is considered the most exact. Unlike politics or economics, or even the more quantifiable disciplines of chemistry and physics, every question in mathematics has a definite yes or no answer. The answer to a question such as whether there is an infinitude of prime numbers leaves absolutely no room for ambiguity or error – it’s a simple yes or no (yes in this case). Not surprisingly, mathematicians around the beginning of the 20th century started thinking that every mathematical question that can be posed should have a definite yes or no answer. In addition, no mathematical question should have both answers. The first requirement was called completeness, the second one was called consistency. Read more »

Cancer has occupied my intellectual and professional life for half a century now. Despite all the heartfelt investments in trying to find better solutions, I am still treating acute myeloid leukemia patients with the same two drugs I was using in 1977. It is a devastating, demoralizing reality I must live with on a daily basis as my entire clinical practice consists of leukemia patients or leukemia’s precursor state, pre-leukemia. My colleagues, treating other and more common cancers, are no better off. I obsess over what I have done wrong and what the field is doing wrong collectively.

Cancer has occupied my intellectual and professional life for half a century now. Despite all the heartfelt investments in trying to find better solutions, I am still treating acute myeloid leukemia patients with the same two drugs I was using in 1977. It is a devastating, demoralizing reality I must live with on a daily basis as my entire clinical practice consists of leukemia patients or leukemia’s precursor state, pre-leukemia. My colleagues, treating other and more common cancers, are no better off. I obsess over what I have done wrong and what the field is doing wrong collectively.

Covid-19 has led to various reactions akin to the various phases in the process of grieving.

Covid-19 has led to various reactions akin to the various phases in the process of grieving.

Many of us read with interest Ben Rhodes’ insider account of his time as a speech writer and advisor to Barack Obama during that historic presidency in his book The World as It Is: Inside the Obama White House. There were suggestions of his displeasure at some aspects of US politics in that publication, as for example the racism he thought Obama was subjected to while in office. His new book After the Fall: Being American in the World We’ve Made, goes further and is a clearer articulation of his concern about US and international politics. The conclusions he draws could be viewed as a personal coming of age in his understanding of the impact of American foreign policy on the world, and indeed experiencing and confronting more realistically, the ‘darker’ angels in US domestic politics.

Many of us read with interest Ben Rhodes’ insider account of his time as a speech writer and advisor to Barack Obama during that historic presidency in his book The World as It Is: Inside the Obama White House. There were suggestions of his displeasure at some aspects of US politics in that publication, as for example the racism he thought Obama was subjected to while in office. His new book After the Fall: Being American in the World We’ve Made, goes further and is a clearer articulation of his concern about US and international politics. The conclusions he draws could be viewed as a personal coming of age in his understanding of the impact of American foreign policy on the world, and indeed experiencing and confronting more realistically, the ‘darker’ angels in US domestic politics. In 1994, Chauvet cave was discovered near the township of Vallon-Pont-d’Arc in southern France. The cave is a

In 1994, Chauvet cave was discovered near the township of Vallon-Pont-d’Arc in southern France. The cave is a  One day, I used to say to myself and anyone else who’d listen, I’m going to write a book called ‘everything you know about these people is wrong’. I have given up on the idea, and I expect anyway that someone else has already done it. What prompted the repeated thought was the way in which so little of what well known thinkers and artists did or said is actually reflected in public consciousness,

One day, I used to say to myself and anyone else who’d listen, I’m going to write a book called ‘everything you know about these people is wrong’. I have given up on the idea, and I expect anyway that someone else has already done it. What prompted the repeated thought was the way in which so little of what well known thinkers and artists did or said is actually reflected in public consciousness,

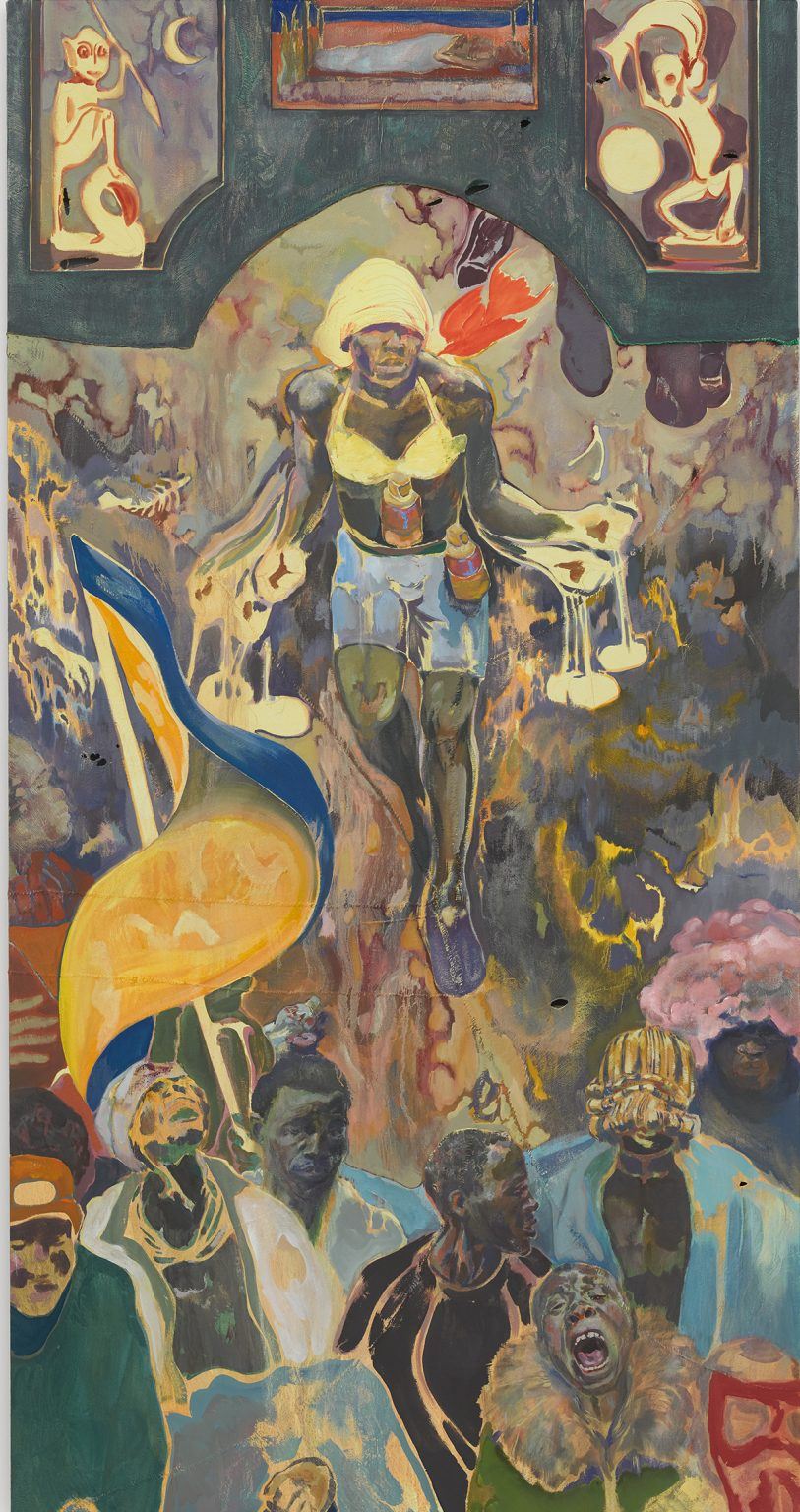

You may know everything that you need to know about the on-going “Critical Race Theory” debate. Indeed, you might have concluded that actually there is no such

You may know everything that you need to know about the on-going “Critical Race Theory” debate. Indeed, you might have concluded that actually there is no such  Where I live in Colorado there are unstable elements of the landscape that sometimes fail. In severe cases, millions of tons of rock, silt, sand, and mud can shift, leading to massive landslides. The signs aren’t always evident because the breakdown in the structural geology often happens quietly underground. The invisible changes can take hundreds or thousands of years, but when a landslide takes place, it is fast and violent. And the new landscape that comes after is unrecognizable.

Where I live in Colorado there are unstable elements of the landscape that sometimes fail. In severe cases, millions of tons of rock, silt, sand, and mud can shift, leading to massive landslides. The signs aren’t always evident because the breakdown in the structural geology often happens quietly underground. The invisible changes can take hundreds or thousands of years, but when a landslide takes place, it is fast and violent. And the new landscape that comes after is unrecognizable. A number of issues in the study of nationalism ought to be widely accepted nowadays, most notably perhaps the claim that political nationalism – the idea that a citizen pledges allegiance to a nation-state rather than to a village or a town – is a modern phenomenon. After all, nationalism properly takes hold in a territory when modern tools such as universal schooling are employed to produce a national identity – the inhabitants of a territory must speak the same language and recognise a common culture if a nation is to surface – and this is a product of the last 200 years. A national identity doesn’t come about on its own.

A number of issues in the study of nationalism ought to be widely accepted nowadays, most notably perhaps the claim that political nationalism – the idea that a citizen pledges allegiance to a nation-state rather than to a village or a town – is a modern phenomenon. After all, nationalism properly takes hold in a territory when modern tools such as universal schooling are employed to produce a national identity – the inhabitants of a territory must speak the same language and recognise a common culture if a nation is to surface – and this is a product of the last 200 years. A national identity doesn’t come about on its own.