by Emrys Westacott

The work ethic is deeply ingrained in much of modern society, both Eastern and Western, and there are many forces making sure that this remains the case. Parents, teachers, coaches, politicians, employers, and many other shapers of souls or makers of opinion constantly repeat the idea that hard work is the key to success–in any particular endeavour, or in life itself. It would be a brave graduation speaker who seriously urged their young listeners to embrace idleness. (I did once hear Ariana Huffington advise Smith College graduates to “sleep their way to the top,” but she essentially meant that they should avoid burn out by ensuring that they get sufficient rest.)

The work ethic is deeply ingrained in much of modern society, both Eastern and Western, and there are many forces making sure that this remains the case. Parents, teachers, coaches, politicians, employers, and many other shapers of souls or makers of opinion constantly repeat the idea that hard work is the key to success–in any particular endeavour, or in life itself. It would be a brave graduation speaker who seriously urged their young listeners to embrace idleness. (I did once hear Ariana Huffington advise Smith College graduates to “sleep their way to the top,” but she essentially meant that they should avoid burn out by ensuring that they get sufficient rest.)

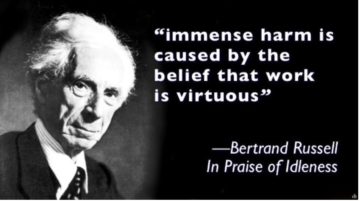

There are, to be sure, some distinguished critics of the work ethic. In a 1932 essay, “In Praise of Idleness,” Bertrand Russell wrote that “immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous.” In his view, “the morality of work is the morality of slaves, and the modern world has no need of slavery.”

But Russell doesn’t really praise idleness as that word is normally understood. True, what he advocates is less work and more free time so that people can spend most of their days doing as they please. But he clearly thinks that some ways of spending one’s time are better than others. He hopes, for instance, that, better education will reduce the chances that a person’s leisure time will be “spent in pure frivolity.” He prefers active recreation, like dancing, to passive recreation, like watching sport. And he strongly prefers cerebral to manual activity. He writes, for instance, that

moving matter about, while a certain amount of it is necessary, is emphatically not one of the ends of human life. If it were we would have to consider every navvy superior to Shakespeare.

(For a brilliant logician, this is an extraordinarily bad piece of reasoning. An activity could be one of the possible ends of human life without being the only end or the “highest” end. Equally remarkable, though, is the intellectual snobbery the statement betrays, suggesting as it does that writing a play is self-evidently a “superior” goal to any kind of skilled feat of craftsmanship or engineering.) Read more »

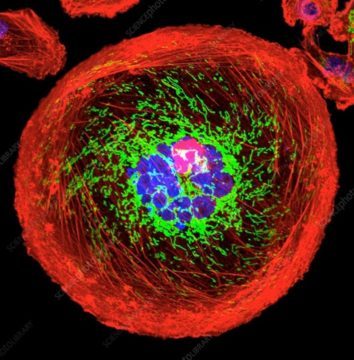

Ninety percent cancers diagnosed at Stage I are cured. Ninety percent diagnosed at Stage IV are not. Early detection saves lives. Unfortunately, more than a third of the patients already have advanced disease at diagnosis. Most die. We can, and must, do better. But why be satisfied with diagnosing Stage I disease that also requires disfiguring and invasive treatments? Why not aim higher and track down the origin of cancer? The First Cell. To do so, cancer must be caught at birth. This remains a challenging problem for researchers.

Ninety percent cancers diagnosed at Stage I are cured. Ninety percent diagnosed at Stage IV are not. Early detection saves lives. Unfortunately, more than a third of the patients already have advanced disease at diagnosis. Most die. We can, and must, do better. But why be satisfied with diagnosing Stage I disease that also requires disfiguring and invasive treatments? Why not aim higher and track down the origin of cancer? The First Cell. To do so, cancer must be caught at birth. This remains a challenging problem for researchers. In the beginning, the god of the

In the beginning, the god of the  In long plane journeys I do not sleep well. But some years back in one such journey I was tired and fell fast asleep. When I woke up, I saw a little note on my lap. It was from the captain in charge of the plane. It said, “I did not want to disturb you, but from our computer log I could see that your total travel so far with our airlines group just crossed 3 million miles. So congratulations! It seems you travel almost as much as I do.” I made a quick calculation, 3 million miles is like 6 return trips from the earth to the moon. With a deep sigh I chanted to myself, as our plane was hurtling through the night sky, a word from an ancient Sanskrit hymn: Charaiveti (keep moving!)

In long plane journeys I do not sleep well. But some years back in one such journey I was tired and fell fast asleep. When I woke up, I saw a little note on my lap. It was from the captain in charge of the plane. It said, “I did not want to disturb you, but from our computer log I could see that your total travel so far with our airlines group just crossed 3 million miles. So congratulations! It seems you travel almost as much as I do.” I made a quick calculation, 3 million miles is like 6 return trips from the earth to the moon. With a deep sigh I chanted to myself, as our plane was hurtling through the night sky, a word from an ancient Sanskrit hymn: Charaiveti (keep moving!)

Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes)

Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes)

One of my oldest friends, an economic historian who serves as the Academic Director of a museum of Jewish life in northern Germany, is, like me, a child of May; and, during our recent birthday month, as is our custom, we exchanged gifts by post. Since we also share a love of books and history and a taste for grand, occasionally outlandish theory, as well as an abhorrence for futuristic science fiction, the novels we sent each other were in equal measures fantastical and backward-looking: examples of counterfactual historical fiction, what has come to be known as uchronia, the imaginative remaking of a bygone era that is the temporal counterpart to utopian geography.

One of my oldest friends, an economic historian who serves as the Academic Director of a museum of Jewish life in northern Germany, is, like me, a child of May; and, during our recent birthday month, as is our custom, we exchanged gifts by post. Since we also share a love of books and history and a taste for grand, occasionally outlandish theory, as well as an abhorrence for futuristic science fiction, the novels we sent each other were in equal measures fantastical and backward-looking: examples of counterfactual historical fiction, what has come to be known as uchronia, the imaginative remaking of a bygone era that is the temporal counterpart to utopian geography.

It wasn’t effortless but we managed to mollify, sidestep and defy enough authorities to be legally resident in Finland for the month of July. Never mind shoes and belts off and toothpaste in a plastic bag. No, do mind; do that too. But add PCR test results, Covid vaccination cards and popup, improvised airport queues. And a novel Coronavirus variant: marriage certificates on demand.

It wasn’t effortless but we managed to mollify, sidestep and defy enough authorities to be legally resident in Finland for the month of July. Never mind shoes and belts off and toothpaste in a plastic bag. No, do mind; do that too. But add PCR test results, Covid vaccination cards and popup, improvised airport queues. And a novel Coronavirus variant: marriage certificates on demand.

Cancer has occupied my intellectual and professional life for half a century now. Despite all the heartfelt investments in trying to find better solutions, I am still treating acute myeloid leukemia patients with the same two drugs I was using in 1977. It is a devastating, demoralizing reality I must live with on a daily basis as my entire clinical practice consists of leukemia patients or leukemia’s precursor state, pre-leukemia. My colleagues, treating other and more common cancers, are no better off. I obsess over what I have done wrong and what the field is doing wrong collectively.

Cancer has occupied my intellectual and professional life for half a century now. Despite all the heartfelt investments in trying to find better solutions, I am still treating acute myeloid leukemia patients with the same two drugs I was using in 1977. It is a devastating, demoralizing reality I must live with on a daily basis as my entire clinical practice consists of leukemia patients or leukemia’s precursor state, pre-leukemia. My colleagues, treating other and more common cancers, are no better off. I obsess over what I have done wrong and what the field is doing wrong collectively.