by David Kordahl

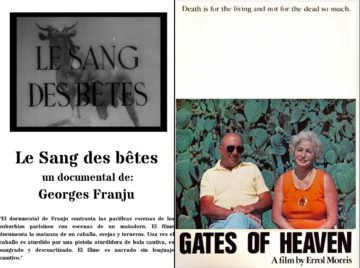

Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes)

Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes)

Georges Franju is perhaps best remembered for Eyes Without a Face (Les yeux sans visage, 1960), an oddly poetic entry in the body horror canon, but Franju’s most memorable film may be his first, Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes, 1949). The only documentary I’ve watched that comes close to its aestheticized brutality is Stan Brakhage’s The Act of Seeing With One’s Own Eyes (1971), which presents forty minutes of silent autopsy footage from the Pittsburgh morgue. Some have suggested that Blood of the Beasts is a comment on the human capacity for cruelty, but I think that’s missing the point. Franju did not aim to accuse. Blood of the Beasts is unique not for what it uncovers about slaughterhouses, but for its pitilessness, for its ironic acceptance of everyday horrors.

The film is only twenty minutes long but seems much longer. It begins with the castoffs of a city—fragments of furniture heaped over a sparse landscape, a nude mannequin in front of a moving train, a pair of lovers kissing—all scored by a simple, nostalgic tune.

The camera lingers for a moment on a bust of A. Emile Decroix. Though the point is not made within the film, one can look up Decroix (1821-1901) to find that he was a military veterinarian who helped to end the ban on eating horses that was in place before the Siege of Paris, when food shortages became so severe that dogs, cats, and rats were also consumed. All the narrator tells us at the beginning is that although the gates of a municipal slaughterhouse are decorated with statues of bulls, it in fact specializes in horses. The tools of the trade are then presented theatrically on a cloth background: a reed, an English axe, a captive bolt pistol.

Into the gate trots a great white horse. The horse’s muscles quiver photogenically. He towers over his handlers. What happens after this is predictable in principle, but almost unbelievable to watch. A captive bolt pistol on the horse’s forehead causes the horse to fall suddenly into a fetal position, legs turned in, head bowed—dead. As the limp horse tips over, a man dives in and slits the corpse’s lip, then plunges a knife in its throat. Read more »