by David Kordahl

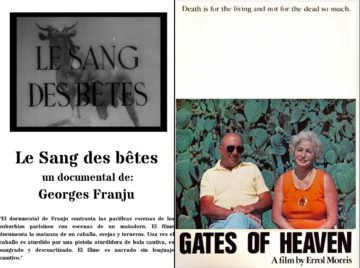

Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes)

Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes)

Georges Franju is perhaps best remembered for Eyes Without a Face (Les yeux sans visage, 1960), an oddly poetic entry in the body horror canon, but Franju’s most memorable film may be his first, Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes, 1949). The only documentary I’ve watched that comes close to its aestheticized brutality is Stan Brakhage’s The Act of Seeing With One’s Own Eyes (1971), which presents forty minutes of silent autopsy footage from the Pittsburgh morgue. Some have suggested that Blood of the Beasts is a comment on the human capacity for cruelty, but I think that’s missing the point. Franju did not aim to accuse. Blood of the Beasts is unique not for what it uncovers about slaughterhouses, but for its pitilessness, for its ironic acceptance of everyday horrors.

The film is only twenty minutes long but seems much longer. It begins with the castoffs of a city—fragments of furniture heaped over a sparse landscape, a nude mannequin in front of a moving train, a pair of lovers kissing—all scored by a simple, nostalgic tune.

The camera lingers for a moment on a bust of A. Emile Decroix. Though the point is not made within the film, one can look up Decroix (1821-1901) to find that he was a military veterinarian who helped to end the ban on eating horses that was in place before the Siege of Paris, when food shortages became so severe that dogs, cats, and rats were also consumed. All the narrator tells us at the beginning is that although the gates of a municipal slaughterhouse are decorated with statues of bulls, it in fact specializes in horses. The tools of the trade are then presented theatrically on a cloth background: a reed, an English axe, a captive bolt pistol.

Into the gate trots a great white horse. The horse’s muscles quiver photogenically. He towers over his handlers. What happens after this is predictable in principle, but almost unbelievable to watch. A captive bolt pistol on the horse’s forehead causes the horse to fall suddenly into a fetal position, legs turned in, head bowed—dead. As the limp horse tips over, a man dives in and slits the corpse’s lip, then plunges a knife in its throat.

Blood pours out in a thick, meaty stream. Gradually, the back legs stop kicking. As we witness these procedures, the narrator coolly describes what we have seen. The horse’s body is then dragged backward though gore into the slaughterhouse, his white coat smeared with blood.

Franju discusses his methods.

“If it were in color, it’d be repulsive”—Franju gave this as his reason for filming in black-and-white. But the monochrome’s message isn’t that these activities are repulsive, it’s that they’re normal. We are shown the process of skinning, for which compressed air must be injected between skin and flesh. The men involved are competent and busy, but they’re not monsters. They smoke while they scrape the skin with lancets.

A close-up of a dead black horse on the floor, and an old photograph interlaid: The narrator informs us that the man in the photo, a corpulent workingman seated on a stool next to another dead horse, is the grandfather of the man who killed today’s black horse.

A book cover closes across the photograph. We’re outside, near the market. Water flows mildly down the Canal de l’Ourcq. Groups of quiet men and women dot the placid cityscape. A group of cattle crosses the bridge from market to slaughterhouse.

While the white horse progressed from steed to steak, it seemed as though the film could offer nothing more terrible, but now when we watch a cow fall in puddle of viscera as it is led inside, we realize that the gory crescendo has only begun.

The cow’s slaughter is more intimately protracted than the horse’s. One man pikes the cow’s forehead with an English axe, and another shoves a reed down the hole to ruin the cow’s spinal cord. We are forced to appreciate the focused effort required to hack a skull apart with a shovel, or to strip a tail inside out. This only amplifies the stark situational ironies. As a carcass is sawed along its sagittal plane, the film crosscuts to the twelve clangs of the noontime bells, and as fat is spooled off flesh, we are told that nuns will come later to retrieve it. (In the epilogue, they do.)

This pattern of intensification continues—but I don’t need to describe exactly how the veal calves are bound and decapitated, or exactly how the sheep scream as their neighbors’ throats are slit, just to make this clear.

“I shall strike you without anger and without hate, like a butcher”: this the narrator quotes from Baudelaire, and adds a phrase about the good humor of killers who whistle, because one has to feed oneself and others. Since Franju does not make it obvious, we must look outside to find that the quoted phrase is from a poem titled “L’Héautontimorouménos,” usually translated as “The Man Who Tortures Himself,” and that the “you” here is the same person as the “I”—in other words, that the film’s true subject is a contradiction in the human character, the contradiction that simultaneously requires the merchant’s civility and the butcher’s violence.

The film ends with the old nostalgic tune playing over a boat that’s leaving for the country, out to fetch more animals.

Gates of Heaven

From behind the camera, Errol Morris watches people talk. This act of watching has occupied the majority runtime of his films, from his eccentric early efforts (Gates of Heaven, 1978; Vernon, Florida, 1981) to his probing political profiles (The Fog of War, 2003; Standard Operating Procedure, 2008). In Morris’s mature style, beginning with The Thin Blue Line (1988), interviewees’ claims are often reenacted, literalized, and played against each other. But it wasn’t always obvious that Morris would become such an active presence in his films.

“There’s your dog, your dog’s dead. But where’s the thing that made it move?”

This quote is from a woman whose pet has just been buried in a pet cemetery, and Gates of Heaven gives no evidence that Morris especially cared where “the thing that made it move” went. Roger Ebert, who called Gates of Heaven one of the ten greatest films ever made, began his “Great Movie” column with this quote and claimed, “No philosopher has stated it better.” But I’m not sure Morris himself would find this question very well posed—at least, I don’t think the young Morris would. The young Morris was more of a caricaturist than an investigator, focused on people’s questions rather than on the truth-claims of their answers.

With such narrow interests, Gates of Heaven is an animal movie in which almost no non-human animals appear. But by refusing to include any of the usual barnyard tropes, it manages to say more about humanity’s relationship to the animal world than most works that are more explicit.

The movie has butterfly structure, with one story in the first half, another in the second, and a connective monologue that belongs to neither and both. The first story is that of the Foothill Pet Cemetery in Los Altos, California. Rather, the first story, related by talking-head interviews with its participants, concerns how the Foothill Pet Cemetery was built on leased land, and how, once the landowner revokes his lease, the buried pets are relocated to Bubbling Well Pet Memorial Park in Napa. The second story is that of Bubbling Well Pet Memorial Park, as told by the family that runs it. The first story is mainly one of failure, and the second, mainly one of success.

Of course, in mortal matters, “failure” and “success” are not so neatly separated. The monologue between the two halves that advances neither one has us listen to a woman whose dead dog is about to be moved.

The connective monologue.

She sits in the doorway in a flat brown wig, wearing scrap dress with a polka-dotted pink apron on top. She’s concerned. She talks about how she can’t walk. How her son should help her. Actually he’s her grandson, who hauls sand—or, wait, now he works in an office. She’ll go after his big office money, just watch. He’s loaded, never been married. Maybe his ex-wife has cleaned him out for child support. Well, maybe she’ll just never grow old. Most people don’t believe it when she tells them her age. And what’s happened to the animals around here, anyway?

Taken too literally, the sheer confusion of this monologue seems out of place in a film that, until then, has concerned itself mainly with the problems of a new business. On repeated viewings, however, the woman’s confusion comes to seem paradigmatic of the human confusion.

The human confusion, that is, toward the rest of the animal kingdom.

Once you begin to look for them, these contradictory human feelings recur throughout. Within the first story, two versions of the same basic confusion are expressed by Floyd McClure, founder of the failed pet cemetery, and Mike Koewler, manager of a local rendering plant.

McClure, a heavy man with suspenders and sideburns, praises his childhood dog, Toby. “Little Toby was put on Earth for two reasons: to love and to be loved.” He recounts his horror (“Hell on Earth,” as he puts it) when he found out Toby was to be taken after death to the rendering plant, a place whose smell was so terrible that people nearby had to sniff wine before they could enjoy the nice meat they were having for supper.

Koewler, for his part, is disgusted by the hypocrisy of people who want to ignore rendering over lunch. (“We were the first recyclers!” he exclaims.) He tells us about his deal with the local zoo: To shut up the whiners, they’ll both affirm that all display animals have been buried. But despite the “real moaners on the phone” who want burials, there are far more who just want the bodies processed before they start to stink.

McClure and Koewler are played as rivals for the purposes of the film, but McClure’s sentimentalism and Koewler’s realpolitik intersect at one point: Neither one considers animals how might interact with the world apart from their place within the speaker’s world. The speakers discuss only what animals can give them, or how animals make them feel.

This mode of discussion stays nearly constant throughout the otherwise variegated talk. No other moment has the ironic heft of McClure’s simultaneous love of animals, hatred of renderers, and enjoyment of meat, but the keepers of Bubbling Well bring in their own set of substitutions.

John Harberts—John Lithgow could play him in a fictional remake—is the family patriarch, and he assures us that his pet cemetery won’t fail. Why? Sound business practices, among other things. (“The pill is probably more responsible for the pet explosion than any other factor in American life.”) This attitude of assured success is best articulated by his older son, who has returned to the family business after a burnout stint as an insurance salesman in Utah. (“I used to call it the R2-A2 formula: Recognize, Relate, Assimilate, and put into Action.”) And while Harberts’s younger son, unable to find other work after college, has more cemetery experience than his brother, his passions are funneled into unheard songs that fill cabin notebooks. (“Dreams are nice to have,” he remarks, sounding unconvinced. “Something to look forward to.”)

Almost as an afterthought, Harberts has invented a religion to compliment his business. He wants to give his patrons “a degree of hope” that they will be reunited with their pets. “Surely at the Gates of Heaven,” Harberts argues, “an all-compassionate God is not going to say, ‘Well, you’re walking on two legs—you can go in. You’re walking on four legs—we can’t take you.’”

By the end, can we say what made the dog move? Cutaways to pet headstones provide scene transitions—“GOD IS LOVE / BACKWARDS IT’S DOG”; “Panda ‘1960-1975’ / I knew love / I knew this dog”—but these sentiments settle nothing. Unvaryingly long, static takes lend credence to the desperation and loneliness of the interviewees, which helps us appreciate the hope they invested in their pets, but as Morris himself has said, “Style is not what guarantees truth.” So what distinguishes these animals from other animals? Just their owners’ love. Which begs the question: Why these animals? Why love these and render the rest?

The film ends with a silent tour of Bubbling Well, with its plastic lawn animals bright in the California sun.