by Thomas Wells

Billions of people around the world continue to live in great poverty. What is the responsibility of rich countries to address this?

Billions of people around the world continue to live in great poverty. What is the responsibility of rich countries to address this?

This essay takes the view that the best we can do is the least we ought to do, but also that the best we can do is heavily constrained by political feasibility as well as logistics. In a democracy the best we can do is what the majority are willing to go along with, and this is something quite different from what purely moral arguments would suggest. For example, rich countries could increase aid programmes from their current pitiful level of $160 billion (less than 0.2% of global GDP). However this would be unpopular since that money could have been spent on more nice things for their own citizens, and lots of rich country governments are already worrying about how to raise the taxes to pay off their Covid debts. Hence that idea fails the political feasibility test. For another example, rich countries could reduce their trade barriers so that poorer countries can access more economic opportunities. Since trade benefits all parties (by definition) this would be a net benefit to rich countries and so it should be politically feasible even though industries threatened with competition would complain. However, rich countries already have very low or zero tariffs on almost everything that is easy to send around the world, so the impact of further liberalisation would be rather tiny.

But there is something else quite obvious that rich countries could do which would have a dramatic impact on global poverty while also having the political advantage of making rich countries even richer. Globalisation has achieved the (more or less) free movement of goods and capital between countries and this has made the world much richer. But people are mostly still stuck behind political borders. Why shouldn’t labour also be allowed to move to wherever it can earn the best price, i.e. to wherever it can be most productive? This would allow rich countries to get cheap low-skilled labour (e.g. to pick our asparagus and care for our old people) while poor people would get access to higher productivity working environments (and hence higher pay) than they could find in their home countries. According to a 2005 calculation by the World Bank, if rich countries globally used migrants to expand their labour force by just 3% this would generate $300 billion in gains for the migrants’ countries (via remittances) and would also save the rich countries more than $50 billion. In other words, rich countries would get even richer while doing far more good for the world than anything else they could try! Read more »

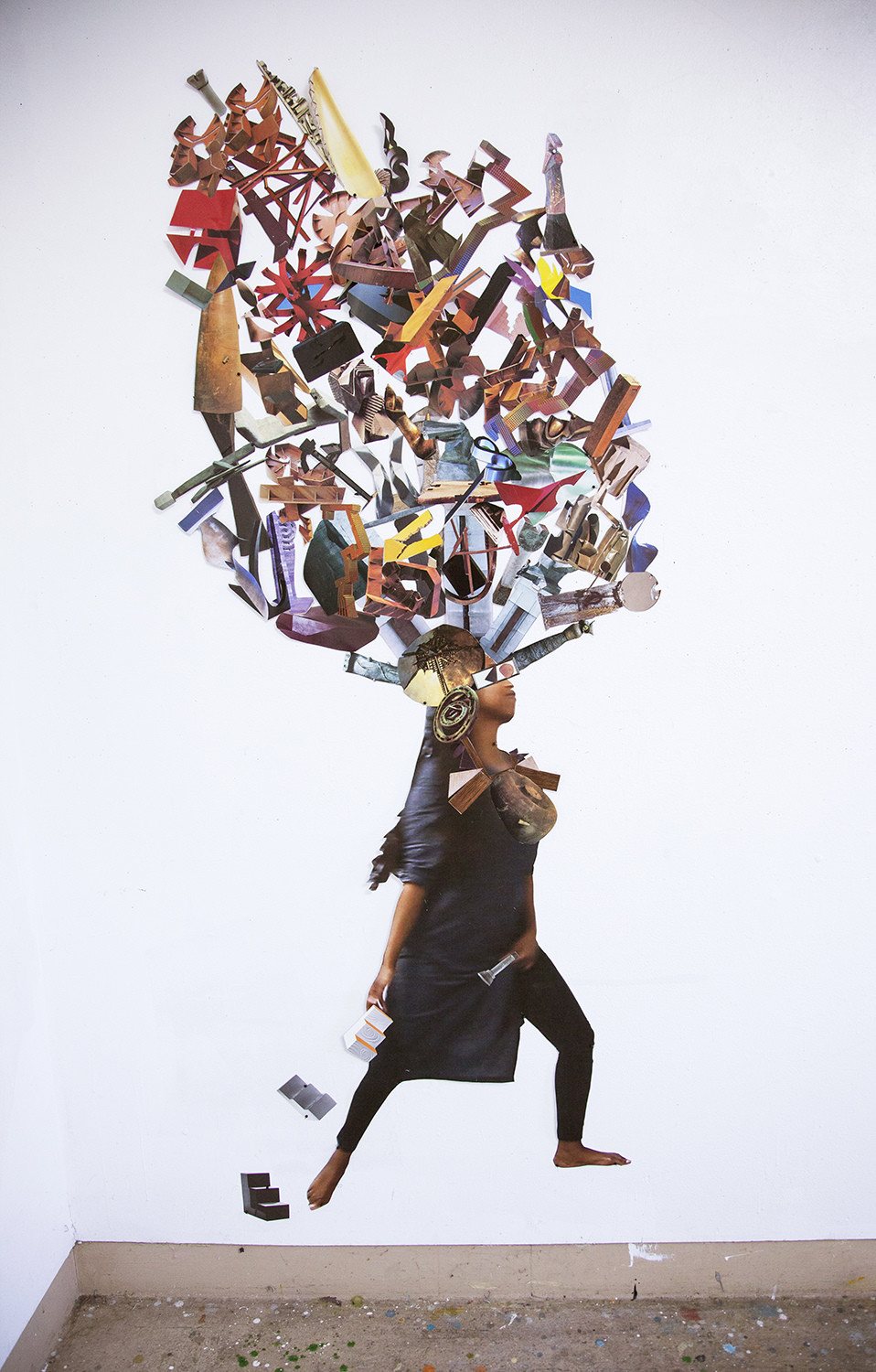

The best thing about a painting is that no two people ever paint the same one. They could be sitting in the same garden, staring at the same tree in the same light, poking the same brush in the same pigments, but in the end none of that matters. The two hypothetical tree-paintings are going to turn out different, because the two hypothetical painters are different also.

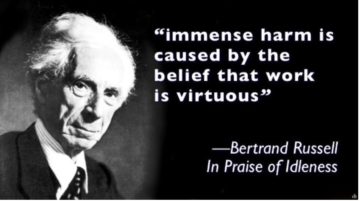

The best thing about a painting is that no two people ever paint the same one. They could be sitting in the same garden, staring at the same tree in the same light, poking the same brush in the same pigments, but in the end none of that matters. The two hypothetical tree-paintings are going to turn out different, because the two hypothetical painters are different also. The work ethic is deeply ingrained in much of modern society, both Eastern and Western, and there are many forces making sure that this remains the case. Parents, teachers, coaches, politicians, employers, and many other shapers of souls or makers of opinion constantly repeat the idea that hard work is the key to success–in any particular endeavour, or in life itself. It would be a brave graduation speaker who seriously urged their young listeners to embrace idleness. (I did once hear Ariana Huffington advise Smith College graduates to “sleep their way to the top,” but she essentially meant that they should avoid burn out by ensuring that they get sufficient rest.)

The work ethic is deeply ingrained in much of modern society, both Eastern and Western, and there are many forces making sure that this remains the case. Parents, teachers, coaches, politicians, employers, and many other shapers of souls or makers of opinion constantly repeat the idea that hard work is the key to success–in any particular endeavour, or in life itself. It would be a brave graduation speaker who seriously urged their young listeners to embrace idleness. (I did once hear Ariana Huffington advise Smith College graduates to “sleep their way to the top,” but she essentially meant that they should avoid burn out by ensuring that they get sufficient rest.)

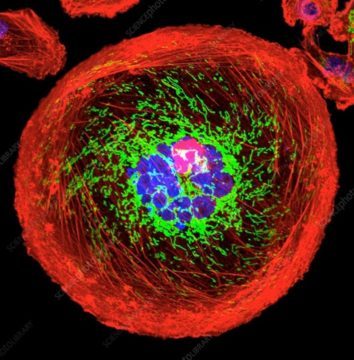

Ninety percent cancers diagnosed at Stage I are cured. Ninety percent diagnosed at Stage IV are not. Early detection saves lives. Unfortunately, more than a third of the patients already have advanced disease at diagnosis. Most die. We can, and must, do better. But why be satisfied with diagnosing Stage I disease that also requires disfiguring and invasive treatments? Why not aim higher and track down the origin of cancer? The First Cell. To do so, cancer must be caught at birth. This remains a challenging problem for researchers.

Ninety percent cancers diagnosed at Stage I are cured. Ninety percent diagnosed at Stage IV are not. Early detection saves lives. Unfortunately, more than a third of the patients already have advanced disease at diagnosis. Most die. We can, and must, do better. But why be satisfied with diagnosing Stage I disease that also requires disfiguring and invasive treatments? Why not aim higher and track down the origin of cancer? The First Cell. To do so, cancer must be caught at birth. This remains a challenging problem for researchers. In the beginning, the god of the

In the beginning, the god of the  In long plane journeys I do not sleep well. But some years back in one such journey I was tired and fell fast asleep. When I woke up, I saw a little note on my lap. It was from the captain in charge of the plane. It said, “I did not want to disturb you, but from our computer log I could see that your total travel so far with our airlines group just crossed 3 million miles. So congratulations! It seems you travel almost as much as I do.” I made a quick calculation, 3 million miles is like 6 return trips from the earth to the moon. With a deep sigh I chanted to myself, as our plane was hurtling through the night sky, a word from an ancient Sanskrit hymn: Charaiveti (keep moving!)

In long plane journeys I do not sleep well. But some years back in one such journey I was tired and fell fast asleep. When I woke up, I saw a little note on my lap. It was from the captain in charge of the plane. It said, “I did not want to disturb you, but from our computer log I could see that your total travel so far with our airlines group just crossed 3 million miles. So congratulations! It seems you travel almost as much as I do.” I made a quick calculation, 3 million miles is like 6 return trips from the earth to the moon. With a deep sigh I chanted to myself, as our plane was hurtling through the night sky, a word from an ancient Sanskrit hymn: Charaiveti (keep moving!)

Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes)

Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes)

One of my oldest friends, an economic historian who serves as the Academic Director of a museum of Jewish life in northern Germany, is, like me, a child of May; and, during our recent birthday month, as is our custom, we exchanged gifts by post. Since we also share a love of books and history and a taste for grand, occasionally outlandish theory, as well as an abhorrence for futuristic science fiction, the novels we sent each other were in equal measures fantastical and backward-looking: examples of counterfactual historical fiction, what has come to be known as uchronia, the imaginative remaking of a bygone era that is the temporal counterpart to utopian geography.

One of my oldest friends, an economic historian who serves as the Academic Director of a museum of Jewish life in northern Germany, is, like me, a child of May; and, during our recent birthday month, as is our custom, we exchanged gifts by post. Since we also share a love of books and history and a taste for grand, occasionally outlandish theory, as well as an abhorrence for futuristic science fiction, the novels we sent each other were in equal measures fantastical and backward-looking: examples of counterfactual historical fiction, what has come to be known as uchronia, the imaginative remaking of a bygone era that is the temporal counterpart to utopian geography.

It wasn’t effortless but we managed to mollify, sidestep and defy enough authorities to be legally resident in Finland for the month of July. Never mind shoes and belts off and toothpaste in a plastic bag. No, do mind; do that too. But add PCR test results, Covid vaccination cards and popup, improvised airport queues. And a novel Coronavirus variant: marriage certificates on demand.

It wasn’t effortless but we managed to mollify, sidestep and defy enough authorities to be legally resident in Finland for the month of July. Never mind shoes and belts off and toothpaste in a plastic bag. No, do mind; do that too. But add PCR test results, Covid vaccination cards and popup, improvised airport queues. And a novel Coronavirus variant: marriage certificates on demand.