by Mike O’Brien

I recently listened to an episode of CBC’s venerable science show “Quirks and Quarks”, in which physicist and astrobiologist Dr. Sara Walker discussed her recent book “Life As No One Knows It: The Physics of Life’s Emergence”. The book explores the boundary between living and non-living chemistry, and how understanding these distinguishing criteria can help us to identify life beyond our own planet. One tidbit from the interview is that chemical compounds that require fewer than fifteen assembly steps can be explained without the presence of living processes, while those that require fifteen or more steps are improbable without the involvement of living processes. This got me thinking about the kinds of self-sustaining systems (chemical, organismal, cultural, etc) that allow for the emergence of substances and structures that would likely never arise otherwise. It just so happens that another “rule of fifteen” manifested in the industrial realm this year, in the likely disappearance of an improbable alloy following the commercial failure of its sole manufacturer. That alloy is CPM-15V, produced by Crucible Industries (“CPM” stands for “Crucible Powdered Metallurgy”), which filed for bankruptcy last December, after surviving a previous bankruptcy in 2009.

CPM-15V is a tool steel containing 15% vanadium and 3.4% carbon by weight (among other things). This is about one hundred times the amount of vanadium found in common “chrome-vanadium” steels, like the kind used for wrenches and other high-strength tools, and about six times the threshold of carbon defining a “high carbon” steel. The purpose for this incredibly high vanadium and carbon content is the creation of vanadium carbides, tiny crystals of vanadium and carbon that are much harder than the surrounding steel. In fact, they are so hard that steels with a high vanadium carbide content must be ground with diamond abrasives (or cubic boron nitride, which is slightly less hard but slightly more tough than diamond). These carbides are also much harder than just about any substance that would need to be shaped in an industrial application, making steels like CPM-15V an effective alternative to cemented carbide tooling (which use a deposited layer of tungsten carbide on top of a steel body) for things like milling tools and punching dies. Its relative toughness (compared to pure carbide) and machine-ability allows it to be milled into intricate and thin-sectioned tools would not be possible with cemented carbide, and that would have a shorter service life if made with lesser alloys.

Why do I, a writer who mostly concerns himself with environmental and animal ethics, know so much trivia about obscure tool steels? Read more »

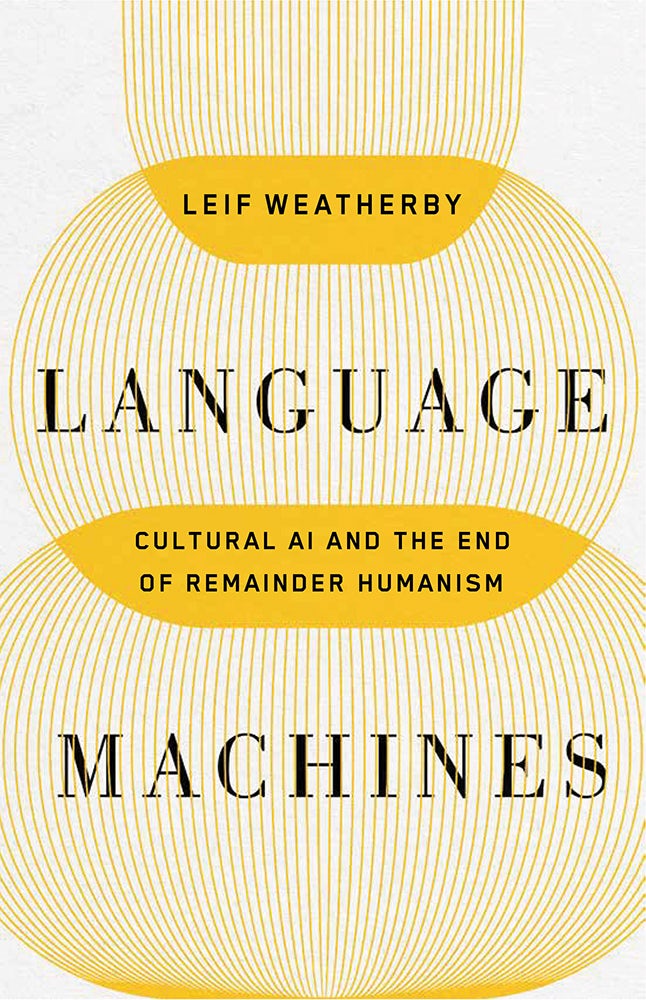

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.

I started reading Leif Weatherby’s new book, Language Machines, because I was familiar with his writing in magazines such as The Point and The Baffler. For The Point, he’d written a fascinating account of Aaron Rodgers’ two seasons with the New York Jets, a story that didn’t just deal with sports, but intersected with American mythology, masculinity, and contemporary politics. It’s one of the most remarkable pieces of sports writing in recent memory. For The Baffler, Weatherby had written about the influence of data and analytics on professional football, showing them to be both deceptive and illuminating, while also drawing a revealing parallel with Silicon Valley. Weatherby is not a sportswriter, however, but a Professor of German and the Director of Digital Humanities at NYU. And Language Machines is not about football, but about artificial intelligence and large language models; its subtitle is Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism.

Every neighborhood seems to have at least one. You know him, the walking guy. No matter the time of day, you seem to see him out strolling through the neighborhood. You might not know his name or where exactly he lives, but all your neighbors know exactly who you mean when you say “that walking guy.” This summer, that became me.

Every neighborhood seems to have at least one. You know him, the walking guy. No matter the time of day, you seem to see him out strolling through the neighborhood. You might not know his name or where exactly he lives, but all your neighbors know exactly who you mean when you say “that walking guy.” This summer, that became me.

For some time there’s been a common complaint that western societies have suffered a loss of community. We’ve become far too individualistic, the argument goes, too concerned with the ‘I’ rather than the ‘we’. Many have made the case for this change. Published in 2000, Robert Putnam’s classic ‘Bowling Alone: the collapse and revival of American community’, meticulously lays out the empirical data for the decline in community and what is known as ‘social capital.’ He also makes suggestions for its revival. Although this book is a quarter of a century old, it would be difficult to argue that it is no longer relevant. More recently the best-selling book by the former Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, ‘Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times’, presents the problem as one of moral failure.

For some time there’s been a common complaint that western societies have suffered a loss of community. We’ve become far too individualistic, the argument goes, too concerned with the ‘I’ rather than the ‘we’. Many have made the case for this change. Published in 2000, Robert Putnam’s classic ‘Bowling Alone: the collapse and revival of American community’, meticulously lays out the empirical data for the decline in community and what is known as ‘social capital.’ He also makes suggestions for its revival. Although this book is a quarter of a century old, it would be difficult to argue that it is no longer relevant. More recently the best-selling book by the former Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, ‘Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times’, presents the problem as one of moral failure.

Sughra Raza. Nightstreet Barcode, Kowloon, January 2019.

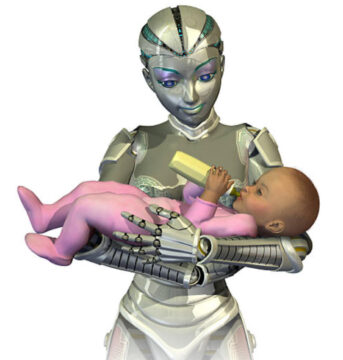

Sughra Raza. Nightstreet Barcode, Kowloon, January 2019. At a recent conference in Las Vegas, Geoffrey Hinton—sometimes called the “Godfather of AI”—offered a stark choice. If artificial intelligence surpasses us, he said, it must have something like a maternal instinct toward humanity. Otherwise, “If it’s not going to parent me, it’s going to replace me.” The image is vivid: a more powerful mind caring for us as a mother cares for her child, rather than sweeping us aside. It is also, in its way, reassuring. The binary is clean. Maternal or destructive. Nurture or neglect.

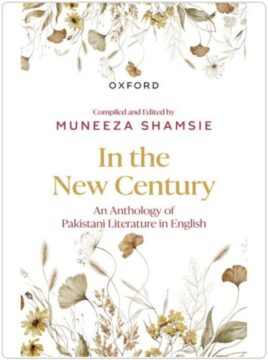

At a recent conference in Las Vegas, Geoffrey Hinton—sometimes called the “Godfather of AI”—offered a stark choice. If artificial intelligence surpasses us, he said, it must have something like a maternal instinct toward humanity. Otherwise, “If it’s not going to parent me, it’s going to replace me.” The image is vivid: a more powerful mind caring for us as a mother cares for her child, rather than sweeping us aside. It is also, in its way, reassuring. The binary is clean. Maternal or destructive. Nurture or neglect. With In the New Century: An Anthology of Pakistani Literature in English, Muneeza Shamsie, the time‑tested chronicler of Pakistani writing in English, presents what is arguably the definitive anthology in this genre. Across her collections, criticism, and commentary, Shamsie has chronicled, championed, and clarified the growth of a literary tradition that is vast but, in many ways, still nascent. If there is one single volume to read in order to grasp the breadth, complexity, and sheer inventiveness of Pakistani Anglophone writing, it would be this one.

With In the New Century: An Anthology of Pakistani Literature in English, Muneeza Shamsie, the time‑tested chronicler of Pakistani writing in English, presents what is arguably the definitive anthology in this genre. Across her collections, criticism, and commentary, Shamsie has chronicled, championed, and clarified the growth of a literary tradition that is vast but, in many ways, still nascent. If there is one single volume to read in order to grasp the breadth, complexity, and sheer inventiveness of Pakistani Anglophone writing, it would be this one.