by Michael Abraham-Fiallos

I sit across from my husband at a Chinese restaurant downtown. We sit outside, in one of those wooden outhouses that Covid has made into a mainstay of New York dining. It is his lunch break, and I have come downtown to meet him, to talk things out. Frankness and care sit with us at the table; they mediate the space between us, between my cabbage and dumpling soup and his shrimp in egg sauce with white rice.

“Why must you bring our past traumas into every argument?” he asks. His voice is steady as he asks it. The question is a question, not an accusation. In his face, I see the desire to understand. “It’s a question I ask myself, too.”

The question strikes a chord, rings a bell deep inside me, sets off alarms I did not know were there. I sit with it a moment. “I don’t know,” I say. “Or,” I continue, “I know, but—”

He finishes the thought for me: “But you don’t know why you can’t just let that tendency go.”

I nod. He nods. We understand what we’ve said and what it means, if not what it means we ought to do. We finish our lunch, and we part with smiles and jokes. We are well. As I walk uptown toward the train, however, I turn the question over and over in my mind. Why must you bring our past traumas into every argument?

*

Fletching is a word we don’t really use anymore because we live in a world of guns. It simply means to affix feathered vanes to arrows in order to make them fly. Fletching is a painstaking labor, a labor performed, one imagines, in days long gone by, only by those with the nimblest and swiftest of fingers. It is beautiful in my imagination, this work—full of colors and textures and needle-like precision. In reality, it was probably arduous and tedious, probably bent the back and wore out the eyes. But, of course, it was necessary, for in a world without guns, what is life without arrows? Read more »

When I was 12 my parents fought, and I stared at the blue lunar map on the wall of my room listening to Paul Simon’s “Slip Slidin’ Away” while their muffled shouts rose up the stairs. As I peered closely at the vast flat paper moon—Ocean Of Storms, Sea of Crises, Bay of Roughness—it swam, through my tears, into what I knew to be my future, one where I alone would be exiled to a cold new planet. But in fact it was just an argument, and my parents still live together—more or less happily—in that same house where I was raised.

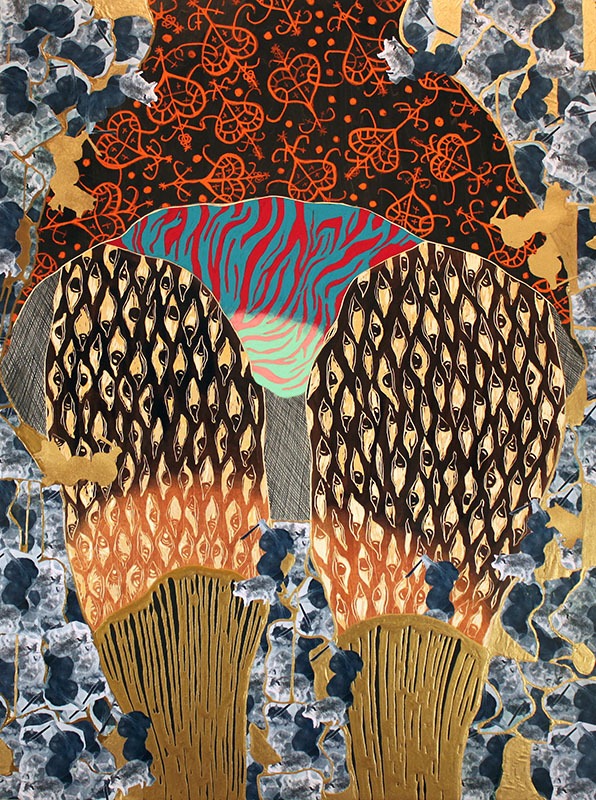

When I was 12 my parents fought, and I stared at the blue lunar map on the wall of my room listening to Paul Simon’s “Slip Slidin’ Away” while their muffled shouts rose up the stairs. As I peered closely at the vast flat paper moon—Ocean Of Storms, Sea of Crises, Bay of Roughness—it swam, through my tears, into what I knew to be my future, one where I alone would be exiled to a cold new planet. But in fact it was just an argument, and my parents still live together—more or less happily—in that same house where I was raised. Didier William. Ezili Toujours Konnen, 2015.

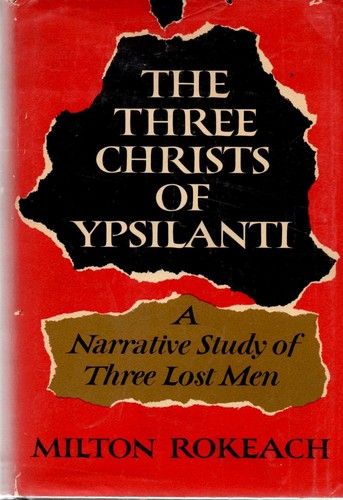

Didier William. Ezili Toujours Konnen, 2015. As an undergraduate History major, I reluctantly dug up a halfway natural science class to fulfill my college’s general education requirement. It was called Psychology as a Natural Science. However, the massive textbook assigned to us turned out to be chock full of interesting tidbits ranging from optical illusions to odd tales. One of the oddest was the story of Leon, Joseph, and Clyde: three men who each fervently believed he was Jesus Christ. The three originally did not know each other, but a social psychologist named Milton Rokeach brought them together for two years in an Ypsilanti, Michigan mental hospital to experiment on them. He later wrote a book titled The Three Christs of Ypsilanti.

As an undergraduate History major, I reluctantly dug up a halfway natural science class to fulfill my college’s general education requirement. It was called Psychology as a Natural Science. However, the massive textbook assigned to us turned out to be chock full of interesting tidbits ranging from optical illusions to odd tales. One of the oddest was the story of Leon, Joseph, and Clyde: three men who each fervently believed he was Jesus Christ. The three originally did not know each other, but a social psychologist named Milton Rokeach brought them together for two years in an Ypsilanti, Michigan mental hospital to experiment on them. He later wrote a book titled The Three Christs of Ypsilanti. “I am by nature too dull to comprehend the subtleties of the ancients; I cannot rely on my memory to retain for long what I have learned; and my style betrays its own lack of polish.”

“I am by nature too dull to comprehend the subtleties of the ancients; I cannot rely on my memory to retain for long what I have learned; and my style betrays its own lack of polish.”

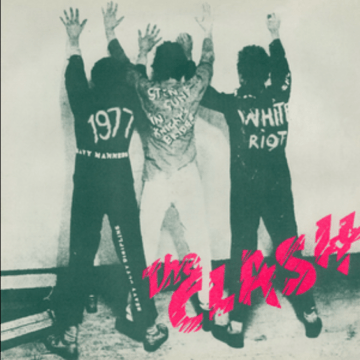

On August 17, 1977, I stopped in as usual at our neighbors’ house, to while away the summer day with my younger brother and sister until our mother’s return home from the university. Our friends – two sets of twins and one singleton – were home-schooled by their mother, and we were all having a summer staycation in any case, so there was always somebody at their house, and a reliably lively time to be had. What met me when I walked into the kitchen that morning, however, was an unaccustomed stillness. All five young people were hovering around the door to the living room while their mother sat at the kitchen table, hunched over a newspaper. “Elvis is dead,” whispered the singleton. Presley had died the day before, in Memphis, in the early afternoon of August 16; but the headlines, and President Carter’s address, would be that day’s news, on the outskirts of Vancouver as elsewhere around the world.

On August 17, 1977, I stopped in as usual at our neighbors’ house, to while away the summer day with my younger brother and sister until our mother’s return home from the university. Our friends – two sets of twins and one singleton – were home-schooled by their mother, and we were all having a summer staycation in any case, so there was always somebody at their house, and a reliably lively time to be had. What met me when I walked into the kitchen that morning, however, was an unaccustomed stillness. All five young people were hovering around the door to the living room while their mother sat at the kitchen table, hunched over a newspaper. “Elvis is dead,” whispered the singleton. Presley had died the day before, in Memphis, in the early afternoon of August 16; but the headlines, and President Carter’s address, would be that day’s news, on the outskirts of Vancouver as elsewhere around the world.

The gully cricket I played in my neighborhood also had a tournament, where different neighborhoods of north Kolkata competed. I once played in such a tournament which was being held in the far north of the city, some distance from my own neighborhood. I don’t now remember the game, but I met there a savvy boy, somewhat older than me, who opened my eyes about Kolkata politics. When he asked me which locality I was from, he stopped me when I started answering with a geographic description. He was really interested in knowing which particular mafia leader my neighborhood fell under. Finding me rather ignorant, he went on to an elaborate explanation of how the whole city is divided up in different mafia fiefdoms, and their hierarchical network and different specialization in different income-earning sources, and their nexus with the hierarchy of political leaders as patrons at different levels. After he figured out the coordinates of my locality he told me which particular mafia don my neighborhood hoodlums (the local term is mastan) paid allegiance to. I recognized the name, this man’s family had a meat shop in the area.

The gully cricket I played in my neighborhood also had a tournament, where different neighborhoods of north Kolkata competed. I once played in such a tournament which was being held in the far north of the city, some distance from my own neighborhood. I don’t now remember the game, but I met there a savvy boy, somewhat older than me, who opened my eyes about Kolkata politics. When he asked me which locality I was from, he stopped me when I started answering with a geographic description. He was really interested in knowing which particular mafia leader my neighborhood fell under. Finding me rather ignorant, he went on to an elaborate explanation of how the whole city is divided up in different mafia fiefdoms, and their hierarchical network and different specialization in different income-earning sources, and their nexus with the hierarchy of political leaders as patrons at different levels. After he figured out the coordinates of my locality he told me which particular mafia don my neighborhood hoodlums (the local term is mastan) paid allegiance to. I recognized the name, this man’s family had a meat shop in the area.

On May 31st, 2021, I sent an email to John Pawelek, Senior Research Scientist at Yale University, requesting a zoom meeting. When a week went by without a response, I decided to call. Searching for his number, I came across his Obituary instead. John Pawelek died on May 31st, 2021. Alas, I missed my chance to speak to a knowledgeable and accomplished scientist.

On May 31st, 2021, I sent an email to John Pawelek, Senior Research Scientist at Yale University, requesting a zoom meeting. When a week went by without a response, I decided to call. Searching for his number, I came across his Obituary instead. John Pawelek died on May 31st, 2021. Alas, I missed my chance to speak to a knowledgeable and accomplished scientist. This year marks the 200th anniversary of Napoleon Bonaparte’s death in exile on the island of St Helena. And it was 206 years ago last June that his career came to a bloody end at Waterloo, with defeat at the hands of an allied army led by Britain’s Wellington and Prussia’s Blucher. But while the Emperor himself is dead and gone, the Napoleon Myth marches on, and is celebrated in some unlikely quarters.

This year marks the 200th anniversary of Napoleon Bonaparte’s death in exile on the island of St Helena. And it was 206 years ago last June that his career came to a bloody end at Waterloo, with defeat at the hands of an allied army led by Britain’s Wellington and Prussia’s Blucher. But while the Emperor himself is dead and gone, the Napoleon Myth marches on, and is celebrated in some unlikely quarters.

Sughra Raza. HAPPY BIRTHDAY JIM CULLENY!

Sughra Raza. HAPPY BIRTHDAY JIM CULLENY! A few years back,

A few years back,